A Male Case against Remote Work

Remote work is a psyop.

What started as a lifestyle perk of only the most avant-garde tech companies in the mid-late 2010s has become a virus that’s infected our working relationships, led to isolation, and undermined human connection. This damage has occurred because of a fundamental misunderstanding of what work is and man’s place in it.

In 2019, less than 6% of Americans worked remotely. In 2020—the height of the COVID pandemic—that number ballooned to 46.3%. Now, it’s stabilized at 28.5%. With their increasing rarity, remote jobs have become such a coveted luxury that some people are willing to take pay cuts to get them. No, the genie isn’t going back into the bottle. In fact, its specter haunts even those who work in-office, whispering like Satan’s serpent: “You do realize your job could be done from the comfort of your own home, don’t you?”

Don’t get me wrong, remote work makes good on many of its promises: you can take calls in your underwear, spend more time at home with your kids (if you have them), and there’s no commute. You can work from any corner of the globe with an internet connection. In short, remote means flexibility.

However, we haven’t fully reckoned with the costs of this flexibility.

I experienced this firsthand during my decade of remote work across different tech companies. I’ve watched my social skills deteriorate. I never made a friend working remotely. I went days without speaking a full sentence with another human in the flesh. I never started any workplace romances. Working remotely gave me panic attacks, existential crises, and soul-crushing isolation. I remember one meeting that set me over the edge. We spent the last ten minutes of the call arguing whether we should use one space or no space after each emoji on Twitter. I closed my laptop after the call and looked at my dog. “Is this it?” I said. “Is this what it’s all been for?”

The personal tolls of remote work far outweigh its shallow conveniences.

Companies, too, are reaping illusory benefits. The debates on remote work’s efficacy usually pit pro-remote workers against return-to-office companies. The main disagreements often come down to efficiency, which workers argue is remote work’s main benefit. Yet this efficiency only exists in the most sterile, autistic understanding of what work actually is.

Sure, some evidence shows that remote work is actually more “efficient”: we save hours each week not commuting and “wasting time” on in-office activities like grabbing lunch with coworkers, chatting at the water cooler, and grabbing coffee. Therefore, we have more time to complete our tasks. But work is far more than completing tasks.

Work doesn’t happen in a vacuum. A company is not a collection of individuals who accomplish interconnected, yet independent tasks in pursuit of a goal. A company is a collision of people, each of whom is more complex than the universe itself, sparking ideas with each other and acting on them. When done correctly, the result is unpredictable, chaotic, and alchemical.

The so-called distractions that remote work mitigates are necessary for this alchemy. The relationships—no matter how superficial or transactional—drive our individual success, both professionally and relationally.

I still don’t know if my remote coworkers were real. I never met them in person, which means there’s a higher than 0% chance they were all AIs. I never made friends with any of them because we couldn’t go out to happy hours together. I never fell in love at work because we couldn’t smell each other. The workplace used to be one of the main places we’d meet our spouses: in 1990, nearly 20% of people met their spouse at work. Now that number is less than 10%. In a Canadian study, 43% of respondents said working remotely has ruined their social skills.

Yes, in theory I could’ve BS’d with my coworkers over Slack, or participated in Zoom happy hours. But those interactions require a choice. In an office setting, you bump into people by virtue of walking to the bathroom, going to the same meeting, grabbing a snack from the kitchen.

Discounting the purportedly time-wasting distractions of the office is like going to a conference and thinking the breakout sessions are the main events. That’s not where the real work takes place. It happens at the bar next door, where a group of new friends who met at the conference happy hour on opening night is meeting for dinner. They understand what work is: it’s a complicated, ever-evolving marketplace of social capital transactions with our fellow primates—one that is impossible to completely recreate online.

No Man Is an Island

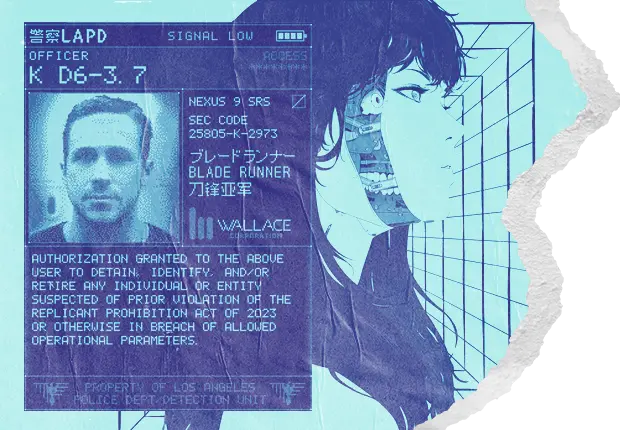

Remote work is counterintuitively stressful. Never mind the fact that it leads to increased loneliness and depression. I’m talking about the stress of realizing remote-work meetings are conversations with the sci-fi-movie equivalent of holograms.

I remember catching myself in a strange existential predicament when I made that realization: how can a remote job cause me anxiety? It’s like being stressed about dying in a video game. If I want to, I can press the power button and turn the whole thing off. Even the paychecks are just a series of digits that show up on my screen every two weeks.

And yet, I could never bring myself to shut down the simulation and its accompanying anxiety. Why?

The zombie apocalypse movie I Am Legend gives us an interesting insight into this phenomenon. In the movie, Will Smith’s character is one of the last people left on earth. Alone, he maintains his sanity by recreating the standard rituals of life, like hitting golf balls, going for drives, and shopping. To give himself some facsimile of human interactions, he places mannequins throughout one video store, talking to them like they’re real people. It’s a self-imposed delusion that’s so effective he eventually develops a crush on one of the female mannequins. But there’s a problem: he’s so nervous in her presence that he can’t even talk to her. (Yes, a mannequin.)

You’d think if it’s actually inducing anxiety, he’d just close the curtains on his private play—after all, this is all his own creation. But the anxiety itself becomes a perverse proof of authenticity. If the anxiety is real, then perhaps the social interactions are real. The anxiety, therefore, helps him maintain the illusion that he’s not alone.

It’s the same with remote work. Why not just close the laptop? Because that would ruin the facade, and force me to admit that remote work is a LARP on par with a mannequin girlfriend in a zombie-apocalypse movie. Never mind that I’m just clicking buttons on my laptop while I lie in bed—if I’m stressed about it, then it’s real, valid work.

Man’s Remote Domestication

Men aren’t meant to work from bed. We’re meant to leave home during the day.

Similar to the quarantine that incited the plot of I Am Legend, remote work reached ubiquity in response to the most HR-lady move of our lifetimes: virus-related lockdowns. It also makes sense that the product of such bureaucratic overreach would be so feminizing for men.

The masculine impulse is to be in the world, conquering something—no matter the scale. It doesn’t matter if you’re typing in spreadsheets, closing sales, or leading the free world; going to work is an echo of man departing for war. You don your suit of armor, kiss your wife goodbye, and venture forth into the day. Perhaps accepting remote work is like a soldier refusing to go off to fight a righteous war. Sure, his wife is happy he’s home. He may even enjoy the arrangement himself—he can spend more time around the kids, help around the kitchen, live the digital nomad life.

But is there not an emptiness to it all? Some unnatural pleasure in your pajama’d existence, like you’ve eaten too many sweets, gazed upon the Ark of the Covenant, witnessed some deep-space anomaly not intended for human eyes. In recompense, you swallow a curse for your unholy indulgences: a lack of polarity in your relationship, a subtle resentment, a mix of duties. “Is she providing? Is he caretaking?”

Remote work muddies relationships. You enter this mode of half-executing, half-living where neither is ever fully on or off. You wanted remote work to give you flexibility? You got it, bub. Now you check your email on the toilet, take calls at 7pm, and refer to your wife as your “partner.”

There’s a saying: “Sit like a tortoise, walk like a pigeon, sleep like a dog.” In other words, when you do a thing, do it all the way—but only one thing at a time. In remote work, you do everything all at once, and none of it completely. This half-on, half-off existence breeds another albatross of the remote blood oath: self-secretarying.

Digital Henpecking

The irony is that remote work could be ideal for deep, focused tasks. If only. Instead, we experience death by a thousand project updates at the hands of HR types who inevitably infest every remote job like project-managers-cum-commissars. What’s more, we spend countless hours doing the incessant secretarial duties—like managing our calendars and responding to messages—that these HR types would’ve been doing on our behalf a few short decades ago.

What a shame. Killing the secretary and placing her corpse in HR has led to a dearth of specialists and a surplus of generalists. This shift blunts the Remote Man. Unfortunately, though, it also renders him more valuable to the same companies that have stolen his killer’s edge. “Wow, you can actually do some content writing even though you’re a salesman? That’s great—we’ll add that to your duties.”

The self-secretarial, generalist-by-necessity Remote Man is like a child who was abandoned at a young age: he’s forced to grow up too young, then praised for his maturity. “I didn’t ask for this,” he says. “It’s all just a highly-tuned coping mechanism.”

Because of the proliferation of the generalist, remote work makes everyone more dispensable. It changes the labor pool from qualified people who live near the company to any qualified person in the world with an internet connection. Similarly, for the Remote Man, companies themselves become interchangeable digital abstractions. If things don’t immediately work out for either party, company or man can be tossed aside in exchange for some other promised panacea. After all, since everyone can do everything there’s almost certainly a better option just around the bend.

Man Is Not a Lab Rat

Our attempts to reconcile with the unreality of the remote work charade are almost comical. I saw a conversation online about best practices for productivity and psychological well-being when working from home. One guy commented saying he gets dressed for work, leaves the house, walks around the block, and goes back to his home office so he can mentally switch into work mode. This is lab rat behavior. In remote work, we are both subject and scientist—Will Smith and mannequin—trying desperately to replicate the conditions of the very thing we’re avoiding: going into work.

You get to wear your sweats during Zoom meetings? You get a $25 DoorDash credit for lunch on Fridays? You don’t have to commute to an office? Congratulations. Does your masculine heart feel satiated by the pacifying conveniences bestowed upon you by the HR class? Was it worth handcuffing yourself to the nest of your own mediocrity?

Like Dostoyevsky said: “Your worst sin is that you have destroyed and betrayed yourself for nothing.” Don’t let the psyops fool you: Return to office is a return to manhood. It’s a return to your conquering impulses. It will not happen at home, Remote Man. It will never happen at home—not until you leave it.