Against the Sheldonians

In Bronze Age Mindset, BAP claims that nerds (of the Big Bang Theory type) love the idea that the universe is fundamentally logic or information. He explains their position as being roughly the belief that “what constitutes matter can in fact be recorded as ‘information,’ as relations of logic, and that therefore the universe must be precisely this—this is behind also the belief that you can “upload” your intelligence to a computer and attain immortality, and many related forms of imbecility.”

He is of course correct that nerds love this idea and that it underpins recent enthusiasm about so-called general artificial intelligence, artificial systems with human-level intellect or greater, as well as lunacy such as Nick Bostrom’s simulation argument which posits a purportedly strong probability that we are living in a computer simulation.

But what exactly is this idea that ties together information-theoretic views of the universe and machine consciousness? What are its alternatives? And why are the Sheldons of the world so entranced by it? I’ll briefly sketch answers to these three questions below. But I would first like to warn my reader against one particular response to this nerdy theory of the world. This response is deflationary, aiming to shrug off the computer-centric nerd world view by reducing its essence to excitement over recent advances in computing technology. Yuval Noah Harari makes such a move in his book Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. He suggests that previous epochs of science were committed to interpreting the world in terms of their most advanced technologies. Enlightenment-era thinkers, on this view, developed mechanical philosophies of the universe because of their fascination with intricate clockwork and other such mechanisms, including eventually technologies like the steam engine. The claim is, we model the world and ourselves after these machines. Hence, in the 20th and 21st centuries, we model the world and ourselves after digital computers.

In the first place, a fine-grained empirical investigation into the history of philosophy and science will reveal a far more complicated picture of what influenced our best theories of ourselves and the world, then and now. But also the nerdish idea that the universe is ultimately information or logic is much, much older than digital computers. We can see shades of this idea even in Plato’s theory of forms. For Plato, the material world we inhabit and sense with our eyes and ears is a fallen and twisted one where everything is constantly changing and hence we can have no real knowledge of it. The only world we can know is the world of the eternal forms, the world our souls left to be here on earth, and the world they will return to when we die. Learning, whether it be philosophical or scientific, is, for Plato, essentially the process of remembering. He calls this kind of remembering anamnesis: we remember what our souls used to know when they inhabited the eternal realm of the forms.

This idea is shared by many philosophies and religions. What’s philosophically essential about this is the idea that what we ultimately exist as disembodied minds, and our material, biological bodies are inessential. You may recognize this idea in one of its modern forms, Descartes “cogito,” or phrase “I think, therefore I am.” Bostrom’s simulation argument and attending theories of uploaded computer consciousness rely on the disembodied cogito to get off the ground. This philosophy allows us to speculate that minds could be realized materially in many different ways which ultimately don’t matter. On this view, it doesn’t matter if we are made of biological neurons or artificial transistors. As long as the right pattern or organization of activity occurs, our consciousness will continue to exist.

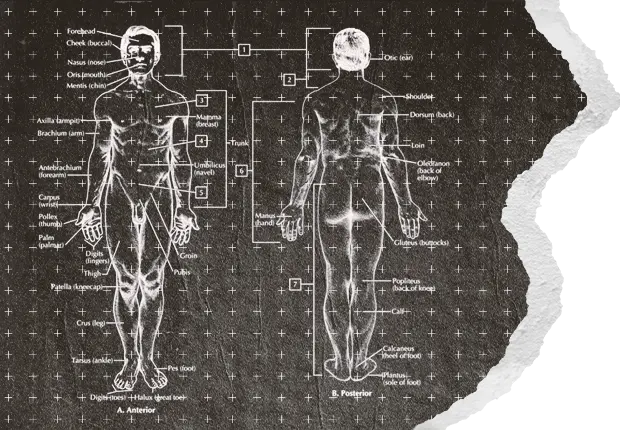

With this philosophical background out of the way, we can now turn to its contemporary, scientific counterpart. The name for this counterpart is computationalism. The essence of computationalism is the claim that minds are computational systems, that is, their workings are logical manipulations of symbols. And these symbols grant us conscious access to an external world in virtue of their capacity to represent that world. This picture of the mind goes something like the following. First, causal processes in the material world impinge on our senses. Light particles strike our retinas and produce electrical signals that get sent to our brain. In our brain, they are processed into pictures or snapshots of the world. These pictures are representations. They re-present the world to us, having been processed by sub-personal and unconscious information systems in our nervous system. All of our conscious experiences are produced this way: they are transformations of information from the external world, specially prepared so that our mind can then use them in thinking about what to do. Once our picture of the world is generated this way, we form attitudes towards these objects of our consciousness. We recognize certain objects like “apple” and “chair,” and we evaluate these objects as good or bad or beautiful or disgusting. Then, having constructed this picture of the world, we act. I’m hungry, and I want to take a bite of the apple, so I reach forward and grasp the apple. On the computational view, the way this happens is the mind issues motor commands, like a robot, to the muscles controlling my limbs, joints, eyeballs, tongue, etc. This sense-think-act cycle repeats over and over, and this series of cycles constitutes our mental life. Indeed, for those like Descartes, it constitutes our being.

The key feature of this picture of the mind is that all its conscious or mental constituents are informational processes, abstractions realized by this or that configuration of matter. In us, they are realized through the electrical signals passing between immense, complex webs of neurons, but, hypothetically, they could also be realized by other types of informational systems, such as a supercomputer. The main consequence of this is that the mental is distinct from the physical and the biological.

The picture of computationalism I’ve just presented is far too swift. It is an idealization of what is otherwise an old and very complicated group of scientific theories, many of which are incompatible with one another. In artificial intelligence and cognitive science, these mental processes were originally conceived of as sets of rules and algorithms. This is sometimes called GOFAI or good old-fashioned artificial intelligence. A GOFAI mental program might run something like this:

- If hungry and food available, eat food.

- I’m hungry.

- The apple is available.

- Eat the apple.

On reaching (4), the body executes the required motor commands for apple eating. These would be explicit commands such as those used in robots for calculating specific joint angles in the shoulder, elbow, wrist, fingers, jaw, etc. It is easy to see how enormously complicated those motor commands would become, but it is also clear how in principle, at least, this picture of cognition could account for the sense-think-act cycles that constitute our mental lives.

Another more recent computational theory of mind does away with these explicit rules, and replaces them with the activity of an artificial neural network. ChatGPT works this way, as does the self-driving system embedded in Elon’s Teslas. This second theory is more closely modelled on biological structures. Webs of idealized computational neurons receive input signals, and each neuron decides to fire or not (send a yes or no signal) to the other neuron connected to it. After this immense web of neurons fires or doesn’t, output neurons send output signals. These could be categorization signals like those in object-detection AIs, or they could be instructions for making a sentence, as is the case in ChatGPT. Higher levels of task complexity are achieved by wiring larger and larger webs of neurons together. The thinking architectures of these neural systems are different from their GOFAI, rule-based brethren, but the same sense-think-act pattern is ultimately followed. The point is, whether we are talking about 1950s chess-playing software or Open AI’s latest language model, the computational model is followed. In both cases, the “thinking” in the system is realized by abstract informational processes. This means that if (and it’s a big if) our minds are also ultimately abstract informational processes, we may one day either make machines with minds like our own, or somehow integrate our own minds with such machines. Like Descartes’ cogito, these abstract informational processes are distinct from the material bodies they inhabit. Like Plato’s ideal forms, they belong to an invisible world not apparent to our senses.

Before moving on to a competitor theory, one that does not conceive of life as computation and that does not eschew the material, biological world for an invisible one, I’d first like to suggest a few psychological factors that might make this view of the mind more palatable for some people, such as the Sheldonian nerds (and the old folks like my beloved grandmother who watch the Big Bang Theory).

The first is that the apparent world of matter and biology is nasty, temporary, and above all unfair. It does not admit of equality in any sense. This is psychologically hard for anyone, but more so for some than others. Imagine you have just been at the gym, hit a PR, and gotten a well-deserved pump. You assure yourself that you are stronger than the vast majority and feel pleased. You leave the gym and head to Chipotle. A cute college girl is preparing orders and you’re sure she will be impressed by your three-dimensional deltoids. Only then, disaster strikes. The members of the local college football team file in to the store behind you. You’ve been MOGGED. Despite what you thought at the gym was true, that you are stronger than most, no amount of injections could make you compete with them. They are genetic freaks. Luckily for you, this feeling of being MOGGED passes when you leave Chipotle. But for the Sheldonian, this feeling permeates every moment of their existence. Every time they take the bus or go to the grocery store, this feeling attacks them. Imagine, you are a Distinguished Research Professor! Yes, you’ve published widely, your work is recognized by your peers, and your office smells of rich mahogany. But then, you step into the real world, with all its unfairness, and you are reminded that nobody cares. You aren’t 6’5 and 250lbs. You are bald and ghey.

The psychological torment of this situation has immensely powerful effects on human belief formation. The notion that, actually, the real world is your world of information and abstraction becomes all the more enticing. If only everyone would recognize this, then you would not have to feel MOGGED every time you left your house. Now imagine again that you are not even a Distinguished Research Professor, but an old woman, or an emaciated They/Them. You would feel this same way, and you would be all-too-happy to accept the information-theoretic worldview of the computationalist. Such a critique of the psychological motivation behind the acceptance of this kind of worldview is essentially the same as Nietzsche’s when, in Twilight of the Idols, he judges Socrates’ (Plato’s mouthpiece) last moments as essentially life-negating. In a section titled “The Problem of Socrates” Nietzsche writes, “Concerning life, the wisest men of all ages have judged alike: it is not good… Even Socrates said, as he died: “To live—that means to be sick a long time.” We should read Nietzsche carefully here, especially when he uses the term “wisest” men of all ages. A naive reader might think Nietzsche here means we should agree with these men, because they are wise. But one man’s modus ponens is another’s modus tollens. For Nietzsche, we should view their life-negating conclusion as an objection to the value of their “wisdom.” Why, asks Nietzsche, should we follow the teachings of those philosophers, priests, and scientists, who describe their very biological essence as a sickness? We should not. At least, those of us who can live in the real world, that is, the unfair and unequal one.

What then is left for us who don’t view life as a sickness? Is our worldview, the life-affirming worldview lost to science and philosophy in the 21st century? The answer is yes and no. Yes, because there is another way of conceiving life and mind that does not posit reality as invisible and disembodied, but as immanent to living things, organisms, with all their inequality and nastiness. No, because the scientists currently working in this area are not like us, not readers of Nietzsche or this magazine, not frogs, but ghey hippies. This is not a new situation for us. You may have found yourself in odd company when reading about the evils of seed oils and factory farming. Birkenstock-wearing company. This is one of those times.

The people I am referring to are called enactivists; their philosophy, enactivism. They study mind and life scientifically, but without the metaphysical baggage of the computationalist. Instead, they view consciousness as essentially that which emerges in the interaction between organisms and their environment. The world is, for them, enacted by the activity of living things. It is not a transcendent, invisible world hidden from our senses. Speaking more scientifically now, they reject the sense-think-act cycle described above that’s so central for the computationalists. For them, mind is not an informational abstraction. It is an ever-changing material process, one far more familiar to the pre-Socratic philosophy of Heraclitus than to Plato. Enactivism insists that minds are biological, that they emerged from the requirement to master their environment, to explore, hunt, be hunted, mate, and play. Yes, play. That word may sound odd to you now. It may conjure up visions of a freak schoolmarm who thinks play means fingerpainting and dancing rather than stick (sword) fighting, wrestling, or tree-climbing. This feeling of aversion is what you will find if you go to read the enactivists. Their paradigms of cognition, their case studies through which they develop their philosophy of nature, suffer from a sort of Bambification. In their texts, you will find talk of breastfeeding babies, of dancing and singing in chorus (all good things). But you will not find, for instance, the Peregrine Falcon swooping down on a mouse, though this ought to be just as important for their research as the other examples.

This is what I mean above when I say above that there is and isn’t an alternative to the computational view of mind and world. On the one hand, the enactivists are on the right track. They reject the notion of the true invisible world, promised only to the pious and educated. Instead, they investigate life as its lived in the material and biological world. But they stop when things get nasty. Here, my reader, is where you might come in. There is, now, a possibility for a new science and a new philosophy, but it is currently only practiced here and there by a few, and even then it balks when confronted with its own logical consequences. Life is not just about love and play, but also power and struggle, exploration and above all violence.

If all of this sounds interesting to you, like me, then you may want to read more about what the enactivists have to say. I will give you some arrows, some texts that you mind find helpful in thinking about these things for yourself. But I also give you a warning. The enactivists may seem, at first, unpalatable to you. They choose to take an especially narrow view on the essence of life. If you do seek their philosophy out, I suggest the following. First, suffer through the aversion you may feel to the overweening niceness of their thought. Then, sit and think for yourself. Apply their models and lessons to the broader range of life. This is a path forward. One that is not paved by the Sheldonian lovers of abstraction, logic, and information. It could be paved by us. I implore you: do not hand over the whole tradition of science and philosophy of mind and life to the Sheldonians or the well-meaning by narrow minded enactivists.

Recommended Reading for Enactivism:

Maturana, Humberto R. and Francisco J. Varela. 1987. The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding. Boston: Shambhala.

Varela, Francisco J., Evan Thompson, Eleanor Rosch. 2016. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. Revis ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thompson, Evan. 2007. Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Di Paolo, Ezequiel, Xabier Barandiaran, Thomas Buhrmann. 2017. Sensorimotor Life: An Enactive Proposal, edited by Xabier Barandiaran, Thomas Buhrmann. Oxford: OUP.