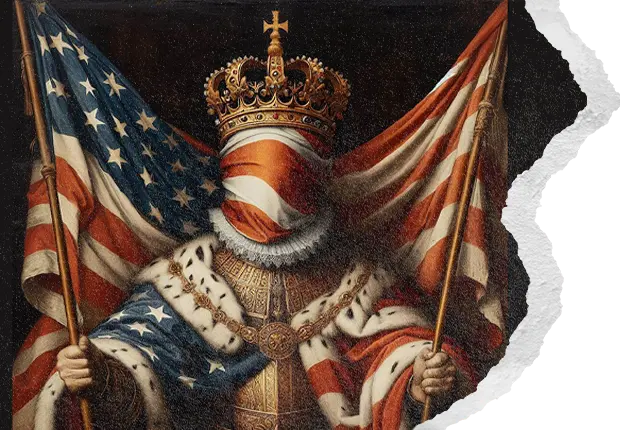

America Awaits Her King

The passing of Queen Elizabeth II and recent coronation of her son King Charles III have given the world cause to reflect on this peculiar institution called the British monarchy — lauded and condemned in turn as a precious patrimony of the British people and an obsolete relic of a shameful past. There’s no doubt that, despite the affectations and pretensions of our democratic age, people the world over remain enthralled by the glory of the tradition, with royal weddings, funerals, and coronations consistently ranking among the most watched events worldwide. Despite its impotence, the British monarchy continues to fill a niche in the Western consciousness which nothing else can, and demonstrates that even in our current age of small souls, the desire to look upon and participate in greatness — or even some facsimile of it — remains an ingredient essential to man’s nature.

Yet, for all their fascination, Americans maintain nearly unanimous hostility to this most time-tested system of political organization. Monarchy in the American psyche has come to be somewhat of a Rorschach test, with all observers projecting onto it everything they hate. For the left: traditionalism, hierarchy, patriarchy, religion, nationhood. For the right: tyranny, big gubmint, gun-grabbing, taxes, and the infamous Goldberg-ian bogeyman of “liberal fascism”. Indeed, anti-monarchism in the Current Year consensus is one of the few things on which all mainstream players agree. And this is no surprise: for generations, the dominant narrative of the Revolution in our civic mythos has been one in which the Patriot cause was synonymous with thoroughgoing radical republicanism, and King George III the archetype of executive despotism inevitably arising from unchecked personal rule. History, so to speak, has been written by the Whigs.

Needless to say, our old friend Mr. Overton tells us the odds of any “American Caesar” in the near-term are thus rather long (the last time a royal was this far outside a window, it was 1618 and the Thirty Years War had just started), but that should be no discouragement. Right is right, after all, and the story deserves to be set straight. Nothing is written, and many things that were once inconceivable have a habit of becoming quite possible. Objects in mirror may be closer than they appear.

The Schoolhouse Rock version of the Revolution is grossly incomplete, and gets key elements of the story exactly backward. As Harvard’s Eric Nelson summarizes in his 2014 revisionist account The Royalist Revolution, “The American Revolution, unlike the two seventeenth-century English revolutions and the French Revolution, was — for a great many of its protagonists — a revolution against a legislature, not against a king. It was, indeed, a rebellion in favor of royal power.”

The simple fact is that at several decisive points in the journey toward American independence, it was not republicanism, Whiggery, or (least of all) Democracy™ at the ideological helm, but royalism. The first of these was during the Imperial Crisis of the 1760s (precipitated by the Stamp and Townshend Acts), in which prominent Patriots including Washington, Franklin, Hamilton, Adams, countless pamphleteers, and even Jefferson found themselves in the Jacobite camp alongside the deposed and beheaded Stuart kings, beseeching George III to reassert royal authority over a tyrannical Parliament. Invoking the terms of their colonial charters, the Patriots argued that the person of the King was their sole source of unity with Britain; that he alone, and not any legislative body, possessed authority to rule the colonies — his personal property. It was not, as the common narrative suggests, the amount of taxation with which the Patriots were chiefly concerned, but their legitimacy. For the Patriots of the Imperial Crisis, the defunction and replacement of the Crown by Parliament constituted a fundamental break from lawful British governance; thus even the most benign law or tax imposed on the colonies by such a body constituted tyranny and de facto slavery.

Even after bullets started flying, the Patriots by and large saw themselves not as rebels against the King, but as the true defenders of Kingly power against republican usurpers. As one British officer recounted of the Patriot forces in 1775, “the Rebels have erected the Standard at Cambridge; they call themselves the King’s Troops and us the Parliament’s”. In Britain, the Parliament, press, and Church alike all lauded George III for resisting the repeated American pleas to restore royal power. Archbishop of York William Markham summarized the sentiment of the British elite of the time: “The Americans have used their best endeavours, to throw the whole weight and power of the colonies into the scale of the crown [and rejected] the glorious revolution. [It was simply through] God’s good providence, that we had a prince upon the throne, whose magnanimity and justice were superior to such temptations.” The British charge against the Patriots was not one of being republican agitators, but reactionary Jacobite extremists — and with good reason.

The royalist cause continued to be decisive after the Revolution and throughout the formulation of the Constitution of 1789, most notably in the design of the office of the Presidency. This point can be illustrated by way of comparison: which is a more powerful office today, the American Presidency or the British Crown? Charles III will hold precisely the same amount of power as George III —that is, none, because it’s the same office. In contrast, the American President under the Constitution of 1789 stood out even among 18th century heads of state for his sweeping executive authority, most notably the veto, which by 1776 had fallen into disuse by the Crown for nearly a century. As Adams remarked, “our presidents, limited as they are, [have] more executive power, than the stadtholders, the doges, the podestàs, the avoyers, or the archons, or the kings of Lacedaemon or of Poland.” Nelson neatly summarizes the concept: in the aftermath of the Revolution, “on one side of the Atlantic, there would be kings without monarchy; on the other, monarchy without kings.” This mere fact alone is damning to the common narrative — a revolution against executive power which results in greater executive power would be an odd thing indeed. That America maintains a presidential system while virtually all post-monarchical European nations have parliamentary systems is no accident of history, but rather reflects the uniquely pro-royal tendencies present from the very foundation of the American project.

All this prompts the question: if royalism was such an influential force in the Patriot cause, why did they put over themselves a president and not a king? To understand this quirk of political history, one must understand the unique blend of royalist, religious, and Whiggish ideas which converged to create the American Constitution.

Royalism took a severe blow as the dominant creed of Patriot thought in 1776 following the publication of the hugely influential anti-royalist pamphlet Common Sense by Thomas Paine, who echoed John Milton (who in turn echoed a particular strand of revisionist Talmudic teaching) in condemning monarchy and its associated titles, honors, and pageantry as inherently idolatrous and sinful. Paine’s promulgation of this revisionist Hebraic interpretation of the Old Testament, in which monarchy itself is “reprobated by the almighty” garnered both high praise and sharp criticism. Adams called Paine’s account “ridiculous,” “foolish,” “willful sophistry and knavish hypocrisy.” Landon Carter of Virginia complained to Washington that Paine had savagely distorted “the Scriptures about Society, [and] Government.” A prominent anonymous reply to the pamphlet compared Paine to Shakespeare’s Shylock: “the Devil can cite Scripture for his purpose.”

Paine’s ideas were controversial to say the least, but one thing they certainly were not was genuine. Adams recalled a conversation with Paine (a deist who once called Christianity “a fable”) shortly after the pamphlet’s publication: “I told him further, that his Reasoning from the Old Testament was ridiculous, and I could hardly think him sincere. At this he laughed, and said he had taken his Ideas in that part from John Milton: and then expressed a Contempt of the Old Testament and indeed of the Bible at large, which surprised me.” But genuine or not, the pamphlet achieved its desired effect of near-single-handedly turning the tide of American sentiment against anything resembling royalty.

The royalist faction compromised on their royalism during the Constitutional Convention to obtain their primary goal of a strong executive, but their compromise was one of cultural sensibility and necessity, not political first principles. Many among them retained their desire to see a proper kingship established over America in the near future. In one letter to Benjamin Rush, Adams made clear his belief that America would eventually need to evolve a proper “hereditary Monarchy” (and aristocracy) “as an Asylum against Discord, Seditions and Civil War, and that at no very distant Period of time” and prophesied the establishment of such an office “the hope of our posterity.” Adams’ view echoed those of Hamilton and Washington, the latter of whom wrote to James Madison shortly before the Convention that, “the period is not yet arrived” (emphasis added) for adopting “Monarchical governm[en]t” but confirmed “the utility; nay the necessity of the form.” The revolutionary sentiment and suspicion of monarchy among the masses made its establishment at the time politically imprudent, but for many Patriots it remained a necessary aim, and ultimate destiny of the American people.

The pros and cons of hereditary vs elected monarchs, of medieval religiously endowed kings vs joint-stock CEO-kings, the particular manner in which such a Restoration would or should be accomplished – all these are outside the scope of this column. Merely, the key point here is that those who wish to see America move on from the democratic delusions of the interregnum have a rightful place within the American tradition, which they need not discard to achieve their aims. The establishment of an American King and fulfillment of the prophecies of Washington and Adams should be understood not as a corruption of the American project, but a refinement; not a departure from the founders’ vision, but an arrival; not a descent into reactionary despotism, but an elevation to a truly well-ordered liberty. America awaits her king. Are her sons up to the task?