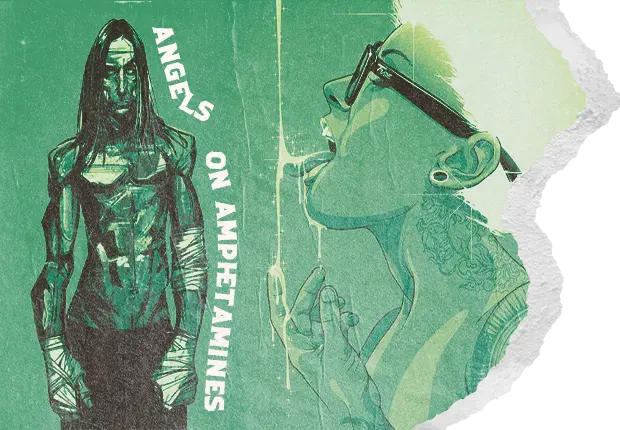

Angels on Amphetamines: American Futurism and the Birth of Rock N Roll

Greil Marcus, the Boomer dean of rock n roll lit crit, wrote a book called Lipstick Traces, published by Harvard, arguing that punk rock is an expression of the same rebel spirit that animated Dada in the early 20th century and Situationism a few decades later. Throughout the book’s 400+ pages, he goes through the history of various obscure avant-garde philosophies and art movements like Surrealism and Lettrism, the anarchism of Stirner and Proudhon, and the proto-punk Symbolism of Rimbaud. The book’s heroes, as far as theorists go, are the Situationist Guy Debord and the Lettrist Isidore Isou, whose ideas he finds mirrored in the early punk rock of the 1970s.

What merits only a brief mention is the Futurist movement founded by F.T. Marinetti in Italy in the early 20th century. This might seem an odd omission since Futurism was a major avant-garde movement which exerted significant influence in art and culture. But it isn’t hard to discern why Lipstick Traces doesn’t want to go there: because “in the 1920s [Futurism] would happily make the leap from avant-garde aesthetics into the new world of fascism,” a leap that Marcus decidedly does not want to make. For him, punk rock is the music of disgust and critique, and that critique of the modern world is necessarily leftist. “Punk,” says Marcus, “was most easily recognizable as a new version of the old Frankfurt School critique of mass culture, the refined horror of refugees from Hitler striking back at the easy vulgarity of their wartime American asylum.”

My intention in this essay isn’t to argue that Futurism is a neglected influence on punk—it isn’t, although it was a direct influence on the Dada movement which Marcus champions. But there was at least one crucial difference between Dada and Futurism. André Gide attended a Dada meeting in the early 20th century and found only “a group of prim, formal, stiff young men [who] … uttered insincere audacities.” R.W. Flint, in his introduction to Marinetti’s Selected Works, notes that

Nothing of the sort could have been said of the hyperkinetic Italians under their galvanic maestro, or of the Russians who adapted Marinetti’s methods to the rather more liberal Russian prewar atmosphere. In postwar Dada, the Futurist enthusiasm had been pacified, ironized and introverted. To claim, as Frank Kermode recently has, that the Dadaists were the original crazies is an odd inversion of the truth.

Hyperkinetic. The original crazies. Gide had asked the stiff young men at the Dada meeting, “What about gestures?” and everyone laughed, for it was clear that, for fear of compromising themselves, none of them dared move a muscle.

Italy, 1909

What was Marinetti’s Futurism? He laid out the essential elements in the first Futurist Manifesto:

- We want to sing about the love of danger, about the use of energy and recklessness as common, daily practice.

- Courage, boldness, and rebellion will be essential elements in our poetry.

- Up to now, literature has extolled a contemplative stillness, rapture, and reverie. We intend to glorify aggressive action, a restive wakefulness, life at the double, the slap and the punching fist.

- We believe that this wonderful world has been further enriched by a new beauty, the beauty of speed. A racing car, its bonnet decked out with exhaust pipes like serpents with galvanic breath… a roaring motorcar, which seems to race on like machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

- We wish to sing the praises of the man behind the steering wheel, whose sleek shaft traverses the Earth, which itself is hurtling at breakneck speed along the racetrack of its orbit.

- The poet will have to do all in his power, passionately, flamboyantly, and with generosity of spirit, to increase the delirious fervor of the primordial elements.

- There is no longer any beauty except the struggle. Any work of art that lacks a sense of aggression can never be a masterpiece. Poetry must be thought of as a violent assault upon the forces of the unknown with the intention of making them prostrate themselves at the feet of mankind.

- We stand upon the furthest promontory of the ages!… Why should we be looking back over our shoulders, if what we desire is to smash down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the realms of the Absolute, for we have already created infinite, omnipresent speed.

- We wish to glorify war—the sole cleanser of the world—militarism, patriotism, the destructive act of the libertarian, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women.

- We wish to destroy museums, libraries, academies of any sort, and fight against moralism, feminism, and every kind of materialistic, self-serving cowardice.

- We shall sing of the great multitudes who are roused up by work, by pleasure, or by rebellion; of the many-hued, many-voiced tides of revolution in our modern capitals; of the pulsating, nightly ardor of arsenals and shipyards, ablaze with their violent electric moons; of railway stations, voraciously devouring smoke-belching serpents; of workshops hanging from the clouds by their twisted threads of smoke; of bridges which, like giant gymnasts, bestride the rivers, flashing in the sunlight like gleaming knives; of intrepid steamships that sniff out the horizon; of broad-breasted locomotives, champing on their wheels like enormous steel horses, bridled with pipes; and of the lissome flight of the airplane, whose propeller flutters like a flag in the wind, seeming to applaud, like a crowd excited.

With these audacious proclamations and exhortations—partly Nietzschean, partly Byronic, but mostly something new and entirely his own—Marinetti made quite a splash, and quite a name for himself. The press dubbed him “the caffeine of Europe” and he gladly embraced this title: the awakener, the raiser of its metabolism, the accelerator of its processing and use of energy. He and others put on “Futurist evenings” in rented theaters, during which they would showcase their writings or other works and spur each other on. An attendee at one such evening in Naples gives an account:

Suddenly a storm broke in the orchestra seats, the room was beginning to divide in two: friends and enemies. The latter inveighing against the Futurists in gusts of insult and profanity, fists shaking, faces twisted into masks. The others clapped insanely. “Viva Marinetti! . . . Abbasso! … Viva! … Abbasso! … Idiots! … Cretins! Sons of whores!” The whole was crowned by a rain of vegetables: potatoes, tomatoes, chestnuts …an homage to Ceres. Finally, in a moment of calm (very relatively speaking), the chief of Futurism began. . . .

No amount of goodwill can reconstruct his exordium that night. You could make out words only once in a while; you heard bursts of his powerful voice and saw his cutting, flailing gestures. He seemed a very stubborn, strange lion-tamer to want to master such a seraglio.

Among whom a mediocre writer of dialect comedies, seized by one of his sadder inspirations, yelled at Marinetti:

“Dentist!”

He should never have said it, this poor man, blind in one eye, drooling at the mouth, worm-eaten. He heard the lightning answer:

“And you are the rotten tooth that I will pull out!” …

The theater is in full revolt. Marinetti begins declaiming Buzzi’s “Hymn to the New Poetry.” But after the noise unchained by Boccioni, a recital of verses made up of lights and shades is impossible, unthinkable. Outside the theater it’s Piedigrotta: tumult, sea-quake.

The Futurists come out, shoved, trampled, heaved around. Cries, howls from every side: “There they are! Look at them! The Futurists!”

America, 1955

If rock n roll has a psychologist whose ideas embody the same values as the music, it would have to be Wilhelm Reich. Reich’s theories about sexual repression causing neurosis and illness—and conversely, sexual expression and fulfillment being productive of mental and physical health—became popular and influential in intellectual circles around the same time that rock n roll became popular with the young. Elvis the Pelvis gyrating wildly on stage is the music video version of Reich’s The Function of the Orgasm; a visual, visceral illustration of “orgastic potency,” which then had to be censored by the television cameras.

The sexual energy and suggestiveness of early rock n roll songs becomes much more apparent when you realize that the word “rock” is just a euphemism for “fuck.” As Sam Phillips says in the Jerry Lee Lewis biopic Great Balls of Fire, “Hell, everybody knows ‘whole lotta shakin’ is what humpin’ is all about!” Elvis’ second single on Sun Records was “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” in which he sings “I’m gonna hold my baby as tight as I can, tonight she’ll know I’m a mighty, mighty man… We’re gonna ROCK all our blues away.” Eddie Cochran’s “Twenty Flight Rock” tells the amusing story of a man whose girlfriend lives on the 20th floor of a walk up apartment building, so that when he gets “to the top, I’m too tired to rock.” The song that first broke rock n roll into the mainstream was Bill Haley and the Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock,” about rockin’ all night long.

Everything that conservative critics said about rock n roll when it first emerged in the mid 50s is true. There’s another scene in Great Balls of Fire where Jerry Lee responds to a teenage fan who says her mama doesn’t like her listening to rock n roll because it “leads to impure thoughts.”

“Well her mama’s RIGHT!” Jerry Lee shouts back, as he stops playing and stands up at his piano. “It is the devil’s music.”

The Rhino box set Loud, Fast and Out of Control: The Wild Sounds of 50s Rock begins with a brief clip of Rev. Jimmy Snow, one of many Southern preachers who engaged in a failed crusade against the devil’s music:

Rock N Roll music and why I preach against it: I believe that it is a contributing factor to our juvenile delinquency of today. I know what it does to you. And I know the evil feeling that you feel when you sing it. I know the lost position that you get into—and the beat! Well, if you talk to the average teenager of today and you ask them what it is about rock n roll music that they like, the first thing they’ll say is “The beat! The beat! The beat!”

The album then goes immediately into Eddie Cochran’s “C’mon Everybody,” one of the greatest examples of the exciting, contagious, frenetic energy of early rock n roll, with its perfectly syncopated bass, drums and rhythm guitar. It gets under your skin, into your muscles, your nervous system, your bones—as he says in the song, “When you hear the music, you can’t sit still.”

Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock,” and the film of the same title which featured it as the theme song, caused riots in England in 1956 at the Trocadero Theatre. It started with dancing—on the floor, then on the stage—and gradually got more and more out of control until the police were called. When the cops showed up the teenagers fought with them rather than leave peacefully. The Guardian was at a loss to explain this behavior, as were the youthful moviegoers themselves, who told the reporters, “It’s fun, that’s all.” The newspaper chalked up their lively unruliness to “frustration and boredom.” Two years later, Bill Haley and the Comets caused another riot in Berlin when they performed a concert there.

To try to understand rock n roll—early rock n roll, when it first emerged then in the mid 50s—is to try to understand why teenage boys would become so frenzied as to cause a riot just because of a song, and why teenage girls would be so overwhelmed by Elvis Presley that they would become hysterical, scream and faint.

Dionysus

The standard Art History narrative is that Futurism began with Marinetti but then made the crucial mistake of getting too cozy with Mussolini and the Fascists, and so by the 1920s it had all come to nothing. I suppose in a way that’s true, if one limits oneself to people explicitly calling themselves “Futurists” or followers of Marinetti.

Ardengo Soffici, a comrade of Marinetti’s from the early days, said that Futurism was “a strange mixture of D’Annunzianism, Victor-Hugoism, and Americanism.” Despite this, however, Futurism as an art movement never really went anywhere in America. It was championed by the literary critic Gorham Munson, and its influence, direct or indirect, could be seen here and there, but there was never an American Futurism like there was a Russian Futurism, led by the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. The spirit of Marinetti’s manifesto had to wait another fifty years for its “Americanism” to find its American form and expression. But that form would be more powerful and more concrete than any nominally “Futurist” art movement in Europe or anywhere else: American Futurism was the 1950s cultural explosion and rock n roll.

What really made the 50s and early 60s great was a tremendous upsurge of youthful vitality and creativity, represented by rock n roll in music, by Jack Kerouac and the Beats in literature, by James Dean, Marlon Brando and the teenage-rebel phenomenon in film and popular culture, by the youthful and vigorous John F. Kennedy in politics, and by space travel and technological futurism in the sciences. All of these are facets of the same thing, the same zeitgeist—a zeitgeist to which the later 60s counterculture was in many ways a reaction, a derailment and not a continuance.

All these developments came from this great burst of cultural energy, which was analogous to the explosions of the atomic bombs which ended the war ten years earlier. This great accumulation and then release of energy—it took ten years of recovery and growth for it to build up before it exploded—was partly the result of exuberance after winning the war, and partly the result of a great unleashing of sexual energy and passion brought about by victory and triumph, the Eros to the war’s Thanatos. Because so many had died, those who did not felt more strongly than ever the desire to live, to live fully and not constrained by the rules of polite society. There came the desire to break through limitations, whether those limitations were the sound barrier and the Van Allen Belt, or just “how you should behave and what you have to do when you grow up.” Marinetti said “Let’s murder the moonlight.” In a classic show of one-upmanship, JFK says “No—let’s fly to the fucking moon.”

The reason why the conservative critics were powerless against rock n roll is because it is an expression of the primal energies of youth, sex, and violence, the very energies Marinetti extolled and tried to summon two generations before. (Arguably he ignored or downplayed sex in his writings, although in his life he was no less the playboy than D’Annunzio.) These energies are perennial and irrepressible, and they are the necessary foundations of all cultural energy—the difference is merely in how and to what ends they are channeled, and if they are lacking, there is nothing with which to build. These primordial energies reasserted themselves in a particular way during the prosperity of the postwar boom in American life, and rock n roll was the soundtrack. Rock n roll was the music of American Futurism, of Marinetti’s speed and violence and electricity, as well as the technological and space futurism of the newly inaugurated Atomic Age.—As feminists will tell you, a rocket is just a giant penis.

Camille Paglia in Sexual Personae calls these primordial energies Dionysian, after Nietzsche. In a preface to Sexual Personae which was only published separately some years later, she said that “no art form, not even Greek tragedy in Athens’s Theater of Dionysus, ever gave full voice to the Dionysian until our own rock and roll, a raucous development of Romanticism.”

Conservatism—which is to say Christianity, the moral foundation and framework of conservatism in the West—has always tried to contain these energies, to channel them towards what it considers to be more wholesome and constructive ends, principally the family and communal social life. A young man is married off early, fathers children, has to support them, and thus his energy is mostly contained and used up under this yoke. Christianity and conservatism can justly claim that the moral and social constraint which pushes men towards this path and keeps them on it is one of the main foundations of modern Western civilization—it creates an order out of chaos.

Early rock n roll was not necessarily opposed to this order; it had not yet developed the destructive impulse that emerged in the 1960s when rock became the music of the counterculture. Rock and rockabilly were primarily about peak experience, an overflowing of joy and energy which was sorely lacking in the pop music of the 40s and early 50s. A song like “Church Bells May Ring,” an early doo-wop single by The Willows from 1956, celebrates marriage and is as wholesome as any gospel song, but its uptempo beat and unrestrained happiness set it apart from the more subdued style of earlier crooners. There is a direct evolution from this song to later songs like 1962’s “Never Let You Go” by the Five Discs, which takes the uptempo sound of “Church Bells” and accelerates it to the absolute limit. It’s the sound of newlyweds speeding down the highway to their honeymoon, unable to contain themselves, their joy so overflowing they have to scream. The happiness has become ecstasy—it’s the sound of angels on amphetamines. Sonny James had a hit song called “Young Love” which sings about young love, but “Never Let You Go” actually sounds the way young love feels.

Whole Lotta Shakin

“For one should make no mistake about the method in this case: a breeding of feelings and thoughts alone is almost nothing (this is the great misunderstanding underlying German education, which is wholly illusory); one must first persuade the body. Strict perseverance in significant and exquisite gestures together with the obligation to live only with people who do not ‘let themselves go’—that is quite enough for one to become significant and exquisite, and in two or three generations all this becomes inward. It is decisive for the lot of a people and of humanity that culture should begin in the right place—not in the ‘soul’ (as was the fateful superstition of the priests and half-priests): the right place is the body, the gesture, the diet, physiology; the rest follows from that.”

— Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

R.W. Flint called the Futurists “hyperkinetic.” The television stations banned Elvis for the way he danced. Michael Ventura, in an essay on the African aspects of rock n roll, takes Greil Marcus and other critics to task for missing this essential, physical aspect of the rock n roll phenomenon:

How typical that the best writers on these men—see Greil Marcus’ crucial chapters on Elvis Presley in his superb Mystery Train, and Nick Tosches’ great biography of Jerry Lee Lewis, Hellfire—virtually ignore the importance of how these men moved. Elvis’ singing was so extraordinary because you could hear the moves, infer the moves, in his singing. No white man and few blacks had ever sung so completely with the whole body.

This rediscovery or reawakening of the body is one of the most important aspects of the rock n roll phenomenon. Ventura notes that “It is no coincidence that the first generation reared on rock’n’roll is the generation to initiate the country’s widespread aerobics movement.” I would add also the bodybuilding craze of the 70s and 80s, which extended to Hollywood and action movies, to which hair metal and hard rock was closely linked as the soundtrack.

Writing in 1919, a decade after the first Futurist manifesto, Marinetti said that a Futurist is “anyone who loves the open-air life, sport, and gymnastics, and pays close attention to the strength and agility of his own body, every day. Anyone capable of delivering a punch or a knockout blow …” The physicality of rock n roll is not so much trained gymnastic as wildness. Rock n roll was the first youth music—Marinetti likewise said of the Futurists: “The oldest among us are thirty.” It extolled energy and exuberance, anti-domestication. Marlon Brando’s defining role was The Wild One about a brooding biker outlaw, and his look from that film had a huge influence on the rock n roll greaser aesthetic: the solitary young man in a leather jacket and jeans who knows everything about cars and engines, who is irresistible to women, who can and will fight you if necessary, or maybe just for fun. It’s become an American archetype, from Arthur Fonzarelli in Happy Days to Social Distortion’s “Sick Boy” anthem.

The greaser aesthetic was only one of several that flourished alongside rock n roll. S.E. Hinton’s famous novel The Outsiders showcased the conflict between greasers and “socs”—upper class kids who would later be called preps. What was common to both was a concern with style and looksmaxxing. In the film La Bamba about Richie Valens, there is a scene of Richie at home in his dirt poor, almost favela-like neighborhood in California, nonetheless ironing his slacks to make sure he looks as good as possible despite his economic limitations. It reminds me of Eddie Cochran’s “Pink Peg Slacks,” about a kid who sees a pair of stylish pants in a store window and he’s just “gotta have ‘em” because he knows they’ll impress a girl, so he sets about to beg, steal or borrow in order to get them. Billy Joel reminisced about 50s stylishness in his nostalgic “Keeping The Faith”

We wore Matador boots, only Flagg Brothers had ‘em with the Cuban heel

Iridescent socks with the same color shirt and a tight pair of chinos

Put on my shark skin jacket, you know the kind with the velvet collar

And ditty-bop shades, yeah …

I thought I was the Duke of Earl

When I made it with a redhead girl

In a Chevrolet

The Futurist cult of the automobile, which R.W. Flint thinks may have come from Gabriele D’Annunzio, flourished in rock n roll from the very beginning. The song widely considered to be the first rock record is Jackie Brenston’s 1951 “Rocket 88,” an ode to an Oldsmobile. A decade later car songs were virtually a subgenre of rock n roll, with classics like “Hey Little Cobra” by The Rip Chords, “Little GTO” by Ronny & the Daytonas, and the Beach Boys’ “Little Deuce Coupe.” (Why were the cars always little?)

Marinetti’s Futurist ode to fast cars, “To My Pegasus,” would have been understood by cruisers and drag racers from New York to California.

Vehement god from a race of steel,

Automobile drunk with space,

Trampling with anguish, bit between your strident teeth!

O formidable Japanese monster with forge,

Nourished with flame and mineral oils,

Hungry for horizons and sidereal prey,

I unleash your heart to the diabolical vroom-vroom

And your giant radials, for the dance

You lead on the white roads of the world.

Lastly I loosen your metal reins and you soar,

Drunkenly, into freedom-giving Infinity!…

When you look back at what cars looked like in 1910 or 1920, this poem almost doesn’t make sense. It wasn’t until the 1950s that cars, including race cars, really came into their own, aesthetically and powerfully, and became worthy of this sort of praise.

Camille Paglia wrote

Byronic youth-culture flourishes in rock music, the ubiquitous American art form. Don Juan’s emotional and poetic style is replicated in a classic American experience: driving flat-out on a highway, radio blaring. Driving is the American sublime, for which there is no perfect parallel in Europe. Ten miles outside any American city, the frontier is wide open. Our long, straight superhighways crisscross vast space. Mercury and Camilla’s self-motivating speed: the modern automobile, plentifully panelled with glass, is so quick, smooth, and discreet, it seems an extension of the body. To traverse or skim the American landscape in such a vehicle is to feel the speed and aerated space of Don Juan. Rock music pulsing on the radio is the car’s heartbeat.

This American sublime found its perfect expression in the Modern Lovers’ great anthem “Roadrunner.” The song was written in 1969 and first recorded a few years later with John Cale, but it wasn’t properly released until 1976, and then only in a rerecorded version considerably less energetic than the Cale version, which is the one to listen to. Jonathan Richman, the songwriter and lead singer, stands out as an artist who understood the 50s zeitgeist for what it was and celebrated it in his music. I don’t think there has ever been a more earnest songwriter in rock n roll, and he is especially to be commended for celebrating the joys of Americana at a time—the1970s—when pessimism and criticism were the order of the day, following the counterculture’s disastrous implosion the previous decade.

Decline

What happened to rock n roll? What happened to 50s vitalism? For a brief time, it lived on into the 1960s. Josiah Bunting described his generation which came of age during the Kennedy years in a speech he gave for the Intercollegiate Studies Institute:

I am a child of the 60s, but not the 60s that you have been led to believe was the 60s. There was a peculiar little wedge generation between the decline of General Eisenhower and the arrival of the Vietnam war and all of that, in which the 60s were dominated by the likes of John Kennedy and the brains trust he brought with him to Washington. It was a time of aspiration, of order, of ambition. But not literally ambition for money. People did not talk about houses in Long Island or German automobiles—they wanted to get a PhD in philosophy, or they wanted to be a priest, or they wanted to be a Green Beret, or they wanted to be in the Peace Corps. It was a very, very different time, but it was a time in which the notion that intellect, educated and trained intellect, put at the service of public policy, could make a great difference in the world. It was a quite remarkable little wedge period that we had there. … There are not a few 65, 70 and 75 year old conservatives walking around who were part of that Kennedy generation, and still remember with great solicitude and affection what that generation represented. If you were in college at that time, you were the beneficiary of a wonderful generation of relatively young professors. These were professors who for the most part got their PhDs under the the G.I. Bill, so they would have been 40 or 45 years old when we were in college. They were terrific professors, they had been through the war, they had seen a lot, and we, many of us, were taught by a peculiar hybrid that no longer exists in the American university, and it’s a shame that that hybrid no longer exists: fiercely traditionalist and conservative in matters of pedagogy and curriculum, and liberal in politics: You will study calculus, you will study Greek, you will do a hundred push-ups, if you’re late you will not be in Phi Beta Kappa, and I’m voting for Adlai Stevenson.

This continuance of the 50s into the early 60s, and the essential stylistic discontinuity between the early and late 60s, was shown most starkly in Mad Men. The show begins in 1960 and ends in 1970, and it makes clear that 50s vitalism very much continued right until the assassination of JFK in 1963. Regardless of what one thinks of Kennedy as a President and politician, there is no question that his murder was a trauma for the entire nation, from which it has never really healed, because of the events which have followed, and because the assassination remains shrouded in secrecy and lies even 60 years later. Michael Hoffman sees the JFK assassination as a catalyst for the abrupt changes seen in Mad Men:

What ought to be unambiguous to a student of mass psychology is the almost immediate decline of the American people in the wake of this shocking, televised slaughter. There are many indicators of the transformation. Within a year Americans had largely switched from softer-toned, naturally colored cotton clothing to garish-colored artificial polyesters. Popular music became louder, faster and more cacophonous. Drugs appeared for the first time outside the Bohemian subculture and ghettos, in the mainstream. Extremes of every kind came into fashion. Revolutions in cognition and behavior were on the horizon, from the Beatles to Charles Manson, from “Free Love” to LSD.

The killers were not caught, the Warren Commission was a whitewash. There was a sense that the men who ordered the assassination were grinning somewhere over cocktails, and out of this, a nearly-psychedelic wonder seized the American population, an awesome shiver before the realization that whoever could kill a president of the United States in broad daylight and get away with it, could get away with anything.

That 50s vitalism was in some respects the precursor to the 60s counterculture is certainly true. Jack Kerouac acknowledged as much when he was interviewed by William Buckley in 1968, just a year before he died. What Kerouac said about the Beat movement—that it began as a movement of “beatitude, pleasure in life, and tenderness” which was then hijacked by “hoodlums and communists”—is true in the larger sense about 50s vitalism and the subsequent 60s counterculture. But just as Jonathan Bowden said there is no reason that early 20th century Modernism necessarily had to become left-wing (it did not begin as such, but as a right-wing cultural movement), there is no reason that the 50s cultural explosion necessarily had to become the 60s counterculture. Elvis and Bill Haley singing the pleasures of sex, teenage boys racing hot rods, getting into fistfights, and peacocking, does not inexorably lead to hippies in polyester stoned out of their minds and protesting everything that came before them.

Or, maybe it had to. Camille Paglia wrote

The Dionysian was trivialized by Sixties polemicists, who turned it into play and protest. Pot on the picketline. Sex in the romper room. Benign regression. But the great god Dionysus is the barbarism and brutality of mother nature. … Dionysus liberates by destroying. He is not pleasure but pleasure-pain, the tormenting bondage of our life in the body. For each gift he exacts a price. Dionysian orgy ended in mutilation and dismemberment. The Maenads’ frenzy was bathed in blood. True Dionysian dance is a rupturing extremity of torsion. The harsh percussive accents of Stravinsky, Martha Graham, and rock music are cosmic concussions upon the human, volleys of pure force. Dionysian nature is cataclysmic.

Perhaps the dissolution of the 60s was the price exacted by Dionysus for the gifts of the previous decade. This is essentially the theme of E. Michael Jones’ book Dionysos Rising, which seeks to link the music of Richard Wagner and Arnold Schoenberg with rock n roll and the 60s counterculture—all of which, in his view, are expressions of Nietzsche’s philosophy and are anti-Western, anti-Christian and wholly negative and destructive. I don’t agree. Aside from the fact that Jones’ reading of Nietzsche is very disingenuous and relies heavily on discredited medical diagnoses and the fictional speculations of Thomas Mann, the more important and fundamental issue is that Jones misunderstands not only the Dionysian but the relationship between the Dionysian and the Apollonian. He takes the identification of Dionysus with the satyr and Christianizes it into Dionysus as Satan, agent of chaos and destruction, enemy of the order of nature, which is the order of God. But it is precisely in their understandings of the “order of nature” that Nietzschean paganism and modern Christianity diverge.

Jones writes,

The common denominator, then, for the medical, the moral, the musical, the political, the theological, and the astronomical, is reason and measure. All things created by God participate in the being of their creator through the reasonableness that lies at the heart of their being. Proper order is synonymous with the divine mind, which makes it synonymous with Love and with the Good and, therefore, with the Beautiful. … Music bespeaks a receptivity to the order of nature apprehended through reason, rather than a false order imposed on nature by man’s desires.

This is the conservative version of Greil Marcus saying that punk is about wanting to be the “subject of history” and to escape “ideological constructs”—that is, it’s reading into music, and more importantly into nature, what you want to hear in it from your favorite books.

What is the “order of nature”? To find out, we must try look to nature itself without preconception; we must observe biological life and try to understand its ways. In doing so, do we find “reason and measure” as the guiding principles of nature? In some ways, yes: the planets maintain their orbits, the seasons ebb and flow according to pattern; a human life has a beginning, middle and end. But as Nietzsche saw, like Heraclitus before him, there is no opposition or contradiction between chaos and cyclicality, or repetition. We also find in nature disorder, violence, predation, suffering, death. The “order of nature” is both order and chaos, stillness and activity, tenderness and ferocity, creation and destruction—Apollo and Dionysus, like the ancient Chinese symbol of the Tai Chi showing the interconnectedness of Yin and Yang. The conservative view, which is to say the modern Christian view, wants only order without chaos, only good without bad, only life without death. This is ultimately rooted in the tenets of the religion itself as it understood today: a God who is only good, who overcomes death—which is seen not as a part of nature but as unnatural, as the “wages of sin”—and which looks forward to a time when “the lion shall lie down with the lamb.”

This reminds me of censored nature documentaries in which the prey always narrowly escapes the predator, as though animals just frolic all day and never eat, never kill. The musical version of this narrow vision of the Good, the True and the Beautiful is Lawrence Welk playing bland orchestral numbers for an audience of bowtie-wearing true conservatives, no one daring to move their bodies lest they lose “reason and measure,” just as Gide described the Dada meeting he attended.—The Harmony of the Spheres as muzak. For Nietzsche, it is this partial and incomplete vision which is the “false order imposed on nature by man’s desires.”

Camille Paglia writes

We say that nature is beautiful. But this aesthetic judgment, which not all peoples have shared, is another defense formation, woefully inadequate for encompassing nature’s totality. What is pretty in nature is confined to the thin skin of the globe upon which we huddle. Scratch that skin, and nature’s daemonic ugliness will erupt.

When Jones says that rock n roll—and before it Wagner, Nietzsche, jazz and the entirety of what I have called 50s vitalism—led to the Dionysian frenzy of Altamont in 1969 and the general excess and burnout of the 60s counterculture, he is not entirely wrong. But it’s a bit like saying that youth leads to old age. To say that therefore the 50s explosion never should have happened is to wish for a stasis in life which—aside from being impossible—is ultimately nihilistic. It is to neglect the essential energies which were the motive force behind it, energies which must be cultivated and harnessed again.

Archeofuturism

Every great era has looked back to a previous great era for inspiration. Renaissance Italy looked back to the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire looked back to the Republic and to Greece. Classical Greece looked back to Homeric Greece. In American history, the 1950s in many ways stands out as a Golden Age. A time of prosperity and strength. A time of social harmony, of optimism and hope for the future. A time when order prevailed but its shadow, the Dionysian, also found expression—a creative rather than destructive expression, which spurred new growth and progress.

Is what I write here an over-simplification, maybe even a whitewashing? Yes. Do you think the Renaissance Italians were interested in digging into what life in ancient Rome “was really like for regular people”? Do you think the Classical Greeks busied themselves worrying about all the hoi polloi that Homer didn’t mention in his epics? No, because for them, history served as myth. When history serves as myth it can become an inspiration to future generations, an aspiration, a model for their own pursuit of excellence. The proper role of past greatness is not something to which we should impossibly seek to RETVRN, as popular memes have it, but rather something that we should seek to emulate with full cognizance and acceptance of our own time and place, with both its limitations and its advantages. As the Japanese samurai classic Hagakure says

It is said that what is called “the spirit of an age” is something to which one cannot return. That this spirit gradually dissipates is due to the world’s coming to an end. For this reason, although one would like to change today’s world back to the spirit of one hundred years or more ago, it cannot be done. Thus it is important to make the best out of every generation.

Thus, while I am sympathetic to William Lind’s concept of Retroculture, I don’t think that larping like it’s 1950 is any kind of answer to American decline. At best such people and communities would become merely another sort of Amish, hiding from the chaos outside, hoping against hope that it does not encroach further. Rather than this, what is needed is what Guillaume Faye called “Archeofuturism,” that is, bringing the values of antiquity into the present in order to create something fresh for the future. This is similar to what Julius Evola advocated in Ride the Tiger, although one needn’t adopt his pessimism and historical determinism, which came from his acceptance of the doctrine of predetermined Yugas, or ages, in time. Dare I say, one could even put a Christian spin on this idea, since it essentially means being in the modern world without being of it.

The split between the Christian Right and the Nietzschean Right is partly about whether today’s problems stem from an absence of the restraining force of Christianity’s moral framework, or an absence of the passion and vigor that it seeks to restrain. The unfortunate reality, I think, is that the constraints of morality had the effect of concentrating passion and vigor, such that when it did explode out of bounds, it did so with greater power. Afterwards, with those constraints loosened by the explosion, the immediate effect was momentary exhilaration and enjoyment, but it has been followed by a slackening, dissipation and exhaustion pretty much ever since then.

In this sense, the trads are right. We do need more more moral constraint. But we should understand that its purpose is to accumulate energy, which will ultimately be discharged in a new cultural explosion. Perhaps that new explosion, that new movement, will be able to avoid some of the mistakes of the past, and not lead to something like the negativity of the 60s counterculture. Or perhaps such processes of decline and decay are inevitable, like death. (The ghost of Oswald Spengler nods his head grimly in the distance.) Regardless, what alternative is there? We find ourselves now in a nadir, in which we have been for decades. We still live on the remaining tattered shreds of the 20th century, one of which is rock n roll, the music of our last genuinely futurist moment.

Is rock n roll still alive? At present, I don’t think so. For the last twenty years, pop music has been dominated not by rock but by hip hop. Maybe rock n roll isn’t dead but only sleeping, like Lazarus in the Bible—or Cthulu in Lovecraft. Perhaps a future generation could rediscover it for themselves, pick up guitars and drumsticks and remake it in their own image, as has already happened several times since the 50s. Whether that will have any bearing on the sorts of cultural changes that we would like to see, I can’t say. Critics can certainly point to many negative effects that rock n roll has had, even in the 50s, before the catastrophes of the 60s.

But to scour history in search of a pure cultural movement or moment is to search in vain. Nature always has its excesses, and its deficiencies. What I have tried to do here is to look at early rock n roll, and the 50s zeitgeist of which it was a part, through the lens of Nietzsche’s heuristic:

Every art, every philosophy, may be regarded as a medicine and assistance to advancing or decaying life; suffering and sufferers are always presupposed. But there are two kinds of sufferers: on the one hand, those suffering from the superabundance of life, who want a Dionysian art, and consequently a tragic insight and outlook; on the other hand, those suffering from the impoverishment of life, who seek repose, tranquillity, smooth sea, or perhaps ecstatic convulsion and languor from art and philosophy. … In respect to artists of every kind, I now make use of this main distinction: has the hatred of life or the superabundance of life, become creative in them?

Someday, perhaps sooner that we think, the primal energies of youth, sex and violence will overflow and explode again from the bowels of the earth like a volcanic eruption, and will make something new, and terrible, and beautiful.