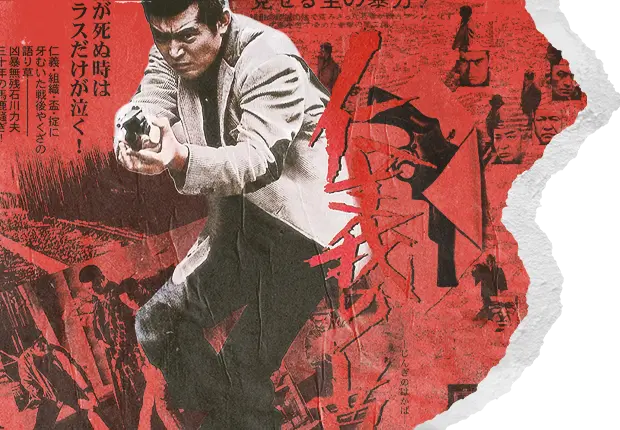

Battles Without Honor and Humanity

Kure, Japan, 1946. The country is irrevocably changed after two atomic bombs and the surrender to US forces. Two US soldiers grab a Japanese woman to partake in the classic wartime conquest, while the defeated populace averts their gaze. A pair of Japanese soldiers intervene to save the woman, starting a violent conflict that leads to a chance prison encounter. Thus begins the classic 1972 film Battles Without Honor and Humanity, directed by Kinji Fukasaku. Part one of a five-part series and based on The Yakuza Papers by Kōichi Iiboshi chronicling Kino Mino’s career as a Yakuza, a Japanese gangster.

The series follows primarily Shinzo Hirono, a Japanese soldier and convict who enters the world of the Japanese mafia searching for purpose and brotherhood. What he finds over the course of five films is a world of violence and betrayal. After meeting Hiroshi Wakasugi and swearing a blood oath in lieu of the traditional sake, Hirono is granted an entrance into the brotherhood.

Not much is revealed about Hirono’s past, his personal life, even his military service. Hirono believes in the ideals of the Yakuza, more than most of his comrades. He dutifully obeys his boss Yoshio Yamamori, despite his being a greedy coward. One might draw a comparison to the democracy defenders and reform advocates, believing in a system that is clearly beyond redemption. Yamamori is despicable, but not exactly evil. He just cares about himself and his wealth: nothing else factors into his planning. In a sense, he personifies the rot at the heart of the Yakuza brotherhood. Instead of a tradition of ideals and respect, it has become a money-collecting bureaucracy.

Moving from Kure to Hiroshima, Hirono builds his own small family (the name given to Yakuza groups, with the boss as a father figure) and a business guarding a scrap yard. He demands loyalty from his men but is a benevolent leader. Hirono places a higher value on the protection of his family instead of wealth. Despite them being low on the hierarchy of families, Hirono doesn’t view their poverty with shame necessarily. This is unusual for Japanese culture, because a lack of clear and distinct success is generally viewed as failure. Perhaps Hirono sees his current circumstances as the consequence for freedom. Maybe freedom is separate from material wealth. Either way, his family is willing to die for him at the drop of a hat. This becomes a source of frustration for him later.

Being young and naïve, the family try to live up to Hirono’s example but also fall into the usual pitfalls of gang life; falling in love with forbidden women, engaging in fights that beget larger conflicts. This last one is intriguing to me, because combat has often distinguished young men from children and gained them acceptance from their elders. Now, it’s mostly in state-sanctioned operations where this is allowed. Street-brawls with wannabe revolutionaries are viewed less enthusiastically by the public. This provides a recurring theme in the film series: that the young are used by the senor leaders as pawns for their own benefit and to the disgust of the middlemen who managed to survive long enough to be promoted.

Those who do manage to rise in the ranks usually do so with great sacrifice. We see two characters introduced who represent the best and worst of the Yakuza ranks: Takeshi Kuramoto, a violent, unemployed youth; and Noburo Uchimoto, an underboss that swears loyalty to whichever family gives him the best chance for promotion while never working for it himself. Kuramoto is recruited into Hirono’s family by his mother and former schoolteacher, who are desperate for any path he may take to be successful, even as a gangster. It’s here we’re briefly reminded of why the Yakuza was formed: to be a place for men who through birth or circumstance are not able to flourish in polite society. The original Yakuza were petty criminals or vagrants who had fallen out of the merchant or sometimes even the warrior class. They staked out their control of gambling halls, which even in preindustrial times were a popular venue for idle Japanese. A handful, like Shimizu Jirochō are regarded as folk heroes for their charity to the community. Bosses who are smart like Yoshio Yamamori buy businesses with the money their underlings earn for them (at great risk to their own wellbeing), and so they have a chance for a safe and legitimate life. Men like Uchimoto, scheme and lie their way into power, upsetting a fragile group dynamic and the convictions of a staunch traditionalist like Hirono. I think you can guess who attains actual success with their strategies.

In film four, Police Action, set in 1963 against the backdrop of the Olympics in Tokyo, there is a concerted effort to end the violence of the Yakuza clans. Much like today, police use surveillance and harassment to try to hobble the Yakuza’s activities. They spy on bosses and search the middlemen, waiting for someone to get sloppy and jail them. The Yakuza are now in retreat, a process that has continue to the present day. The Yakuza now have serious trouble recruiting younger members, and Japanese society has become resigned to stagnation after the economic turmoil of the 1990s, leading to a risk-averse culture.

Hirono by all accounts is the boss that the Yakuza clans deserve, someone who would lay down his own life to spare one of his men, even at the detriment of the clan’s future. He tries to live the code of the Yakuza, even at the cost of his dignity at first. Hirono represents an outdated system in a world that operates by different principles. All around him we see elder figures, entrenched in positions of power and disinterested in dramatic change unless it benefits them. We see middlemen who are disillusioned at their prospects and seem to move out of a sense of obligated automation. At the bottom of all this, we see a pool of fiery and energetic newcomers who are filled with promise and ideals, but struggle to realise them. If you want to understand the recent fortunes of conservative and right-wing groups in the US, you shouldn’t just watch these films: you should take notes.