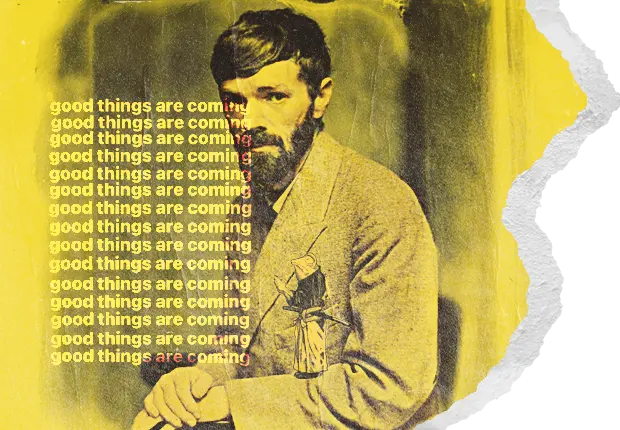

D.H. Lawrence for the Right

“Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically. The cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to have new little hopes.’’ D.H Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover

When one speaks of Right-leaning creatives, the 20th century novelist and essayist D.H Lawrence is not one that springs to mind. After all, Lawrence wrote principally on sex, on youthful men and women, on paganism: these are not themes usually considered conservative. What’s more, the publishers of his novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover were put on trial under British Obscene Publications laws, and their victory in this case is overwhelmingly viewed as a step forward for progressive views on sex and society.

However, times have changed, and the West of Obscenity and Blasphemy Laws is gone. Lawrence lies in the No-Man’s Land of our cultural imagination. The Left engages with his work, with the various waves of Feminism trying to ascertain whether he was a male chauvinist or not, but the Right? Little, and for obvious reasons: his polemical, “obscene” works stood in direct contrast to the austere, stuffy conservatism of the past. It isn’t for nothing that amongst his aphorisms, Nicolas Gomez Davila referred Lawrence to the Reactionary Freak Fringe.

But the times are a-changing, and we have entered uncharted territory. The vitalist philosophy spearheaded by the likes of BAP is a new frontier for Rightist thought, and one that could come to predominate. 21st century vitalists could find much of value in Lawrence and his writing: after all, here is a man who climbed trees naked (a spiritual ancestor of the national nudists perhaps?) and labelled the Revolutionary motto of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity as a “three-fanged serpent.”

A running theme throughout his short stories is vigour, with the youth and energy it entails. In classic works such as Lady Chatterley’s Lover and The Ladybird we see WW1 veterans returning spiritually and physically castrated, with one genuinely unable to make love to his wife and the other unable to bring himself to. The wives themselves find themselves falling in love (love perhaps is too simple a word for what they experience) with more vital, truer, anti-modern men. These lovers shock and provoke, they act as a sexual blackholes from which poor Connie Reid and Lady Daphne are unable to escape.

In Lady Chatterley the lover in question is the gamekeeper Oliver Mellors , a Man Amongst the Ruins, who separates himself from the world, choosing to live in a forest hut and speak in his local dialect. He rages against the sexual chaos of his time, from lesbians to boyish women. Mellors delights in the buxom figure of his woman: Meanwhile, Connie’s husband, Sir Clifford, is resigned to a wheelchair, unable to make love. He spends his time listening to the radio and taking part in pseudo-intellectual circles. Mellors is also a reader—it’s mentioned how his bookshelf contains books on India, amongst others—but not a member of those chattering classes. A clear divide is drawn between the infertile, pseudo-intellectual Clifford, who has grown to despise his wife, and the shier yet truer Mellors, who has grown to love her.

Towards the end of the novel Mellors and Connie manage to escape, yet are forced to separate. He writes her a letter, which displays the full anti-Modern sentiment behind Lawrence’s writing:

“If the men wore scarlet trousers as I said, they wouldn’t think so much of money: if they could dance and hop and skip, and sing and swagger and be handsome, they could do with very little cash. And amuse the women themselves, and be amused by the women. They ought to learn to be naked and handsome, and to sing in a mass and dance the old group dances, and carve the stools they sit on, and embroider their own emblems… and that’s the only way to solve the industrial problem… whereas the mass of people oughtn’t even to try to think, because they can’t. They should be alive and frisky, and acknowledge the great god Pan. He’s the only god for the masses, forever. The few can go in for higher cults if they like. But let the mass be forever pagan”

Similar themes are present in the 1923 story The Ladybird. The “love interest” here takes the form of Count Dionys Psanek, a wounded German prisoner of war. Throughout the novel, Lady Daphne finds herself increasingly drawn to the Count. He reveals more about himself and his homeland in Old Europe, from which he has been taken. Psanek hints towards his dreams of the future, which envision a new kind of man, a man that rejects the Anglo-Saxon world of Enlightenment and Liberalism. Daphne finds herself taken through a semi-religious series of mysteries, which culminate in the Count revealing his true identity. His bloodline has taken as its symbol the

Ladybird, which Dionys identifies with the Pharaohs of Egypt. The Count is represented as

Oriental god, she as god-consort, identified in various points throughout the text as either Isis or Aphrodite. Count Dionys’ parting words:

“If you have to cry tears, cry them. But in your heart of hearts know that I shall come again, and that I have taken you for ever. And so, in your heart of hearts be still, be still, since you are the wife of the Ladybird.”

It perhaps is no wonder some feminist scholars have called out Lawrence’s belief in the supremacy of the male.

But Lawrence is no mere sentimentalist or pornographer. Whilst it’s true he writes lurid sex scenes, and delights in his usage of fuck and cunt instead of gentler words, there is method in his madness. His portrayal of physical love is one that is deeply critical of Modernity and its liberality. He recognised the descent of Western civilisation into a darker age, in which men and women would grow further and further apart. In Odour of Chrysanthemums we see this alienation, with a miner’s wife realising whilst looking at his pallid corpse that they never truly knew each other, beyond the accident of being man and wife.

“Now he was dead, she knew how eternally he was apart from her, how eternally he had nothing more to do with her. She saw this episode of her life closed. They had denied each other in life. Now he had withdrawn. An anguish came over her. It was finished then: it had become hopeless between them long before he died. Yet he had been her husband. But how little!”

Modernity forces its way between men and women, distorting their relations. Ultimately we are beginning to forget what it is to be authentically, simply ourselves. And so Lawrence sees in making love a radical, vital act, in which man and woman are forced to reveal themselves, and physically come together.

Consider the use of modern dating apps, speak to anyone about dating, read the graphs on the political divides between men and women. Everywhere there is sexual confusion, and it is nigh impossible to say Lawrence’s predictions for the West were wrong.

But there is hope, and we find it in the Lawrence work that perhaps would best suit our time, and the present current of dissident thought. This is the 1930 novella the Virgin and the Gypsy. In many ways it is a typical Lawrence story: two young sisters, having moved to a grey Northern village are ruled by “Mater,” their gross, toad-like grandmother, who is the family matriarch and commands from the comfort of her armchair. She has pressed the girls’ aunt into a sexless and solitary life, and both despise the youth, beauty and vitality of their younger family members (if that isn’t a literary description of the Longhouse, I don’t know what is). After one of the girls finds herself drawn to a local gypsy—who, as Masculinity itself embodied, remains nameless till the very end— tensions rise in the household to a crescendo. A great flood sweeps through the house, drawing the grandmother and sweeping her maddening matriarchy away:

“Then a man climbed in cautiously through a smashed kitchen window, into the jungle and morass of the ground floor. He found the body of the old woman: or at least he saw her foot, in its flat black slipper, muddily protruding from a mud-heap of debris. And he fled.’’

Purification of the world?

Lawrence was not an explicitly left-wing nor a right-wing writer. Despite the fact Bertrand Russell labeled him a “proto-German fascist,” he took little interest in that which did not interest him, and so climbed trees naked, travelled across the world, tried to form intentional communities, rode horses in New Mexico. He wrote about paganism, and love, and vitality. The characters in his novels are not virtuous, but they do, in Bronze Age Pervert’s words “keep vice true to themselves.” I do not try to claim Lawrence would have found himself at home with the vitalists of today, but his works have been largely forgotten by the Right, and should be revisited. The conservatives of yesteryear may not have been prepared for D.H Lawrence, but we certainly are.