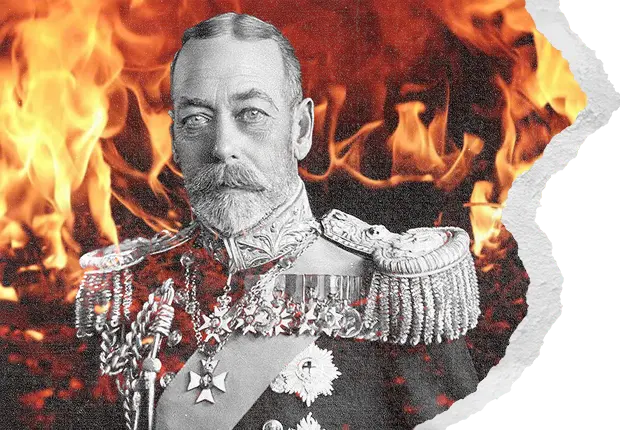

Did George V Betray His Cousin the Tsar?

In his 1923 memoir, Sir George Buchanan, who was British ambassador to Russia from 1910 to 1918, devoted sixteen pages to denying that Great Britain had orchestrated the Russian Revolution.

Why did he need to deny this?

The reason is that prominent Russian exiles were accusing Britain of complicity in the Revolution, among them Princess Olga Paley, widow of the Tsar’s uncle Grand Duke Paul.

In the June 1, 1922 Revue de Paris, Princess Paley wrote: “The English Embassy, on orders from [Prime Minister] Lloyd George, had become a hotbed of propaganda. The Liberals, Prince Lvoff, Miliukoff, Rodzianko, Maklakoff, Guchkoff, etc., met there constantly. It was at the English Embassy that it was decided to abandon the legal ways and embark on the path of the Revolution.”

When Princess Paley identified the British Embassy as the nerve center of the Revolution, she was not just passing along gossip. She had inside knowledge of British operations in Petrograd.

Grand Duke Paul, the Princess’s husband, was deeply involved in the intrigues leading up to the Tsar’s abdication. Her stepson Dmitri had taken part in the assassination of the “mad monk” Rasputin, a British-led operation, according to Andrew Cook’s To Kill Rasputin (2006).

Milner’s Ultimatum to the Tsar

In February, 1917, Lord Alfred Milner – a high-ranking British statesman – traveled to Petrograd to deliver an ultimatum to the Tsar. Russia was on the brink of revolution, Milner warned. To save the monarchy, the Tsar must lay down his traditional autocratic powers and institute democratic government.

Nicholas refused.

The real reason for Milner’s demand was that he knew the Tsar was negotiating a separate peace with Germany. As Princess Paley had observed, the Duma leaders were largely under British control. If the Tsar turned over power to the Duma, Britain would gain effective control of the Russian government.

Palace Coup

The overthrow of the Tsar was, in effect, a palace coup, engineered by Nicholas’s own relatives, working closely with the British Embassy.

On March 14, 1917, British ambassador George Buchanan met with the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, the Tsar’s brother. They discussed plans to force concessions from the Emperor.

Prime Minister Rodzianko was planning to meet the Tsar when he arrived by train that evening, and to demand his signature on a manifesto relinquishing his autocratic powers and instituting a constitutional monarchy, just as Lord Milner had demanded in February.

The manifesto had already been signed by Grand Dukes Paul, Michael and Cyril.

Only the Tsar’s signature was needed now.

King George V Endorses the Revolution

During their meeting of March 14, Grand Duke Michael asked Buchanan if he had “anything special” he would like to convey to the Emperor.

Buchanan states in his memoirs, “I replied that I would only ask him to beseech the Emperor, in the name of King George, who had such a warm affection for His Majesty, to sign the manifesto, to show himself to his people, and to effect a complete reconciliation with them.”

I must assume that Buchanan would have obtained the King’s approval before daring to speak “in the name of King George” on such a grave matter.

This raises the possibility that King George V of England—through his ambassador—may have officially endorsed the Russian Revolution while it was still in progress.

Who Gave the Order?

There is some mystery as to why the Tsar ended up abdicating, rather than signing the manifesto creating a constitutional monarchy.

Buchanan states in his memoirs that the Tsar never saw the manifesto, because the Emperor’s train never arrived that evening.

By the time the Tsar telegraphed Rodzianko the next day (March 15), agreeing to sign the manifesto, Rodzianko told him, “Too late.” Abdication was now the only course left.

Why did Rodzianko change his mind?

Buchanan says the demand for abdication came from the Petrograd Soviet, a group of socialist agitators who had suddenly announced their existence on March 12.

There is a problem with this story, however. Rodzianko did not take orders from the Soviet. He took orders from Buchanan.

Revolution from Above

The Tsar’s overthrow had been well-planned. It was a revolution from above, not below.

When the soldiers mutinied, they did not rampage through the streets. They marched straight to the Tauride Palace, where the Duma met, to pledge their loyalty to Russia’s new rulers.

The London Daily Telegraph of March 17, 1917 reported: “On Tuesday [March 12] the movement rapidly spread to all the regiments of the garrison, and one by one they came marching up to the Duma to offer their services.”

And who led the Duma? They were Buchanan’s men, the same ones Princess Paley accused of conspiring at the British embassy— “Prince Lvoff, Miliukoff, Rodzianko, Maklakoff, Guchkoff, etc..”

Buchanan also had weight with the mob. Following the Tsar’s abdication, he was seen leaving the Winter Palace. Recognizing Buchanan as a friend of the Revolution, the mob in the street “greeted him with loud cheers and escorted him back to the [British] Embassy, where they gave a rousing demonstration in honour of the Allies,” reported The Times of London.

“Dictator” of Russia

On March 24, 1917—nine days after the Tsar’s abdication—a Danish newspaper correspondent reported that Buchanan now wielded the power of a “dictator” in Russia.

He wrote: “England’s domination over the [Russian] government is complete and the mightiest man in the empire is Sir George W. Buchanan, the British ambassador. This astute diplomat actually plays the role of a dictator in the country to which he is accredited. The Russian government does not dare to undertake any step without consulting him first, and his orders are always obeyed, even if they concern internal affairs. …When Parliament is in session he is always to be found in the imperial box, which has been placed at his disposal, and the party leaders come to him for advice and orders. His appearance invariably is the signal for an ovation.”

The imperial box which had been “placed” at Buchanan’s “disposal” was formerly reserved for the Emperor himself.

Given these facts, we must regard with some skepticism Buchanan’s claim that the Petrograd Soviet – during its three-day existence – had somehow acquired more authority than Buchanan to tell Rodzianko what to do.

Milner’s Revenge

The British press made no effort to conceal its glee over the Tsar’s downfall. On the contrary, British journalists implied that the Tsar had gotten what he deserved, for failing to heed Lord Milner’s warning.

“Every effort was shattered by the obduracy of the Tsar,” reported the London Guardian on March 16, 1917. “It is noteworthy that the outbreak [of the Revolution] followed promptly on Lord Milner’s return from Russia, where his failure was generally understood to mean that nothing could be hoped from the Tsar, and that the people must seek their own redemption.”

On March 22, 1917 – with the Tsar and his family under arrest, and their fate uncertain – Great Britain granted recognition to the revolutionary government.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George sent a telegram that day to Russia’s new premier, Prince Lvov, stating, “It is with sentiments of the most profound satisfaction that the peoples of Great Britain and the British dominions have learned that their great ally, Russia, now stands with the nations which base their institutions upon responsible government.”

Meanwhile, former Prime Minister Asquith declared in the House of Commons, “Russia takes her place by the side of the great democracies of the world. …We… feel it our privilege to be among the first to rejoice in her emancipation and welcome her into the fellowship of free peoples.”

Did the British Back the Bolsheviks As Well?

I have written more extensively on this subject in my article, “How the British Invented Communism (And Blamed it on the Jews),” available at richardpoe.substack.com and RichardPoe.com.

Among other questions, my article explores the persistent rumor that Leon Trotsky was a British spy, a charge of which he was actually convicted in a Soviet court (in absentia).

Trotsky personally led the Bolshevik coup on the night of November 6-7, 1917.

He was able to do this only because MI6 had mysteriously released him from a Canadian internment camp six months earlier.

In Moscow, Trotsky reportedly had a fling with Clare Sheridan, reputed British spy and Winston Churchill’s first cousin.

Trotsky’s first act as Commissar for Foreign Affairs was to repudiate Russia’s interests in the Persian oilfields, leaving it all for the British. This windfall greatly increased the assets of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, later known as British Petroleum.

All things told, a lot of our history seems in need of rewriting.

Things are just not what they seem.