Excuses, Excuses, Excuses

Most Latin teachers are failed writers. So are most English teachers, but you have to pity the Latin teachers because they have so much going for them (in theory). Any retard can do an English degree, but Latin takes brains and discipline. So it must suck to spend all that time studying an ancient language, and all the grammar and vocabulary, and struggle through reading classical poetry word by word for years, and memorising half of The Aeneid, and then end up as a teacher.

Some people get the job because they couldn’t get an academic job (you can’t these days unless you’re fat, or a woman, or otherwise the kind of person who gets his feet washed and kissed by Pope Francis). But there are people who become Latin teachers because they actually want to. They figure it’s an easy job that will let them write books on the side, especially poetry books, and those are the Latin teachers you want to watch out for. Every single one of these ones is a failure.

Some of them end up getting arrested for whatever it is they have on their hard drives, but we’re not worried about those ones right now because you can already spot them from a distance. Most of those ones are failed writers too but that’s not the main reason you keep away.

Every failed-writer Latin teacher’s favourite writer seems to be Cyril Connolly. If they like you, they try to tempt you into becoming a failed writer too, so they make you read Cyril Connolly.

Maybe you’ve heard of Cyril Connolly. He once said “imprisoned in ever fat man a thin man is wildly signalling to be let out.” He also said “there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall”. He’s known for a lot of good one-liners (although you’d sound like a faggot if you ever tried to use them in public and pass them off as your own).

He was educated at Eton and Oxford, and he was the most famous literary critic in England from the 1930s until the 1970s, when he died. When he was at Oxford, everybody said he was going to become the next great English novelist. The one novel he finished sucked. He spent the rest of his life complaining he was “born too late” and “didn’t have the luck” and had every excuse in the book for never actually doing anything. He wrote two good books and both of them are about how he didn’t have it in him to write a masterpiece.

His second good one, The Unquiet Grave (1944) actually begins:

“The more books we read, the sooner we perceive that the true function of a writer is to produce a masterpiece and that no other task is of any consequence. Obvious though this should be, how few writers will admit it, or having made the admission, will be prepared to lay aside the piece of iridescent mediocrity on which they have embarked! Writers always hope that their next book is going to be their best, for they will not acknowledge that it is their present way of life which prevents them from ever creating anything different or better.”

You probably read that and said “he’s literally me” (except for his beautiful sentences and superior level of education—you probably had to look up “iridescent mediocrity” in the dictionary). Then you hear him say “happiness lies in the fulfilment of the spirit through the body”. He also says “the reward of art is not fame or success but intoxication: that is why so many bad artists are unable to live without it”. Finally he says:

“Everything is a dangerous drug except reality, which is unendurable. Happiness is in the imagination. What we perform is always inferior to what we imagine; yet daydreaming brings guilt; there is no happiness except through freedom from angst, and only creative work, communion with nature and helping others are angst-free.”

By now you’re probably wondering why you haven’t read any Cyril Connolly before and why he isn’t your hero. He’ll tell you why. Here’s what he says to and about himself on Christmas Eve:

“No opinions, no ideas, no knowledge of anything, no ideals, no inspiration; a fat, slothful, querulous, greedy, impotent carcass; a stump, a decaying belly washed up on the shore. “Manes Palinuri esse placandos!” Always tired, always bored, always hurt, always hating.”

Cyril Connolly is the master of self-pity. He wallowed in self-loathing to make women feel sorry for him, and it actually worked. That was how a fat, ugly, broke, lazy failed writer managed to bed some of the most desirable women in England. He wasn’t powerful like Henry Kissinger. He just activated women’s mothering instinct. His first wife was an eighteen-year-old heiress from Baltimore, and he was the one who dumped her, not the other way around. He wasn’t even that interested in women, but he was too ugly and obese to be gay. He knew it too:

“Obesity is a mental state, a disease brought on by boredom and disappointment: greed, like the love of comfort, is a kind of fear. The only way to get thin is to re-establish a purpose in life. Thus a good writer must be in training: if he is a stone too heavy then it must be because that fourteen pounds represents for him so much extra indulgence, so much clogging laziness; in fact a coarsening of his sensibility.”

You should read The Unquiet Grave, but it’s not nearly as important as Enemies of Promise, which Connolly wrote in 1938 in the south of France to explain how hard it is to be a “promising young writer”. He says it’s almost impossible to write a book that will last even ten years. He himself has his wife’s money, and no job, and still can’t write anything because he gets up too late in the morning to write before lunch, and he can’t write in the evening because he’s part-Irish, and Irish writers always over-write when the sun starts to go down. You have to give him credit, it’s an original excuse for doing absolutely nothing all day long.

Enemies of Promise is dedicated to Logan Pearsall Smith, who was a gay old man from Philadelphia who moved to England to become a writer. But he didn’t have any talent so he became a “gentleman scholar” instead. He prowled around Oxford looking for talented young men, and he would take them out to lunch and become their “mentor” by convincing them that “success” was overrated and what they really wanted to do was have five-hour lunches with gay old men. Cyril Connolly became Logan Pearsall Smith’s secretary until he married his first wife and didn’t need a job anymore.

Enemies of Promise is one of the most self-defeating books you’ll ever read. The first part is a catalogue of writers, mainly from 1900 to 1922. You have to give Connolly credit, he read a lot and he’s a good critic (most of the time). He notices things you and I wouldn’t see. He also writes amazingly well a lot of the time. If you want to teach yourself twentieth-century literature, just read the first section of Enemies of Promise and take good notes, and read as many of the books he talks about as you can. But after a while you get to notice that something’s missing, and you can’t put your finger on it, and it takes a while to see what it is. You’ll figure it out in Part Two.

Here’s where the excuses start:

“We must answer a question sometimes put by certain literary die-hards, old cats who sit purring over the mouseholes of talent in wait for what comes out. “Is this age,” they pretend to ask, “really more unfavourable to writers than any other? Have not writers always had the greatest difficulty in surviving? Indeed, their path today seems much easier than it was, to give an example, for myself!”

“The answer, if they wanted an answer, is yes. Yes, because a writer needs money more than in the ivory tower decade since he can no longer live in a cottage in the country meditating a blank-verse historical drama and still get the best out of himself. Yes, because he is more tempted today than at any other time by those remunerative substitutes for good writing: journalism, reviewing, advertising, broadcasting and the cinema, but most of all because a writer can have no confidence in posterity and therefore is inclined to lack the strongest inducement to good work: the desire for survival.”

You see how he traps himself? He’s “too talented” and “too precious” to live in the time he was born in somehow. If you’re wondering what he means when he talks about “survival”. He’s talking about World War Two on the horizon:

“At any moment the school of Athens may be closed, the libraries burnt, the teachers exterminated, the language suppressed. Any posthumous fame or the existence of any posterity capable of appreciating the arts we care for, can only be guaranteed by fighting for it and for many who fight, there will be no stake in the future but a name in a war-memorial.”

If that sounds a little bit melodramatic, wait until you hear about what he says about right-wingers:

“Today the forces of life and progress are ranging on one side, those of reaction and death on the other. We are having to choose between democracy and fascism, and fascism is the enemy of art. It is not a question of relative freedom; there are no artists in fascist countries. We are not dealing with an Augustus who will discover his Horace and his Virgil, but with Attila or Hulaku, destroyers of European culture whose poets can only contribute battle-cries and sentimental drinking songs.”

He can sort of tell the difference between “fascists” and standard tax-cutting conservatives:

“Capitalism in decline, as in our country, is not much wiser a patron than fascism. Stagnation, fear, violence and opportunism, the characteristics of capitalism preparing for the fray, are no background for a writer and there is a seediness, an ebb of life, a philosophy of taking rather than giving, a bitterness and brutality about right-wing writers now which was absent in those of other days, in seventeenth-century Churchmen or eighteenth-century Tories. There is no longer a Prince Rupert, a Doctor Johnson, a Wellington, Disraeli or Newman, on the reactionary side.”

When he wrote this, Connolly forgot about his own “reactionary” friends T. S. Eliot and Evelyn Waugh, who were the greatest English writers alive back then. But the truth doesn’t matter here. What matters is that Cyril Connolly has deliberately given you two fake options to choose from so that any which way you move you’re screwed, unless you just choose socialism.

Connolly called himself a “liberal” but really he was just a socialist who knew his ideas were going to bring on full-on communism, and he knew it would destroy everything he loved but he liked the feeling of doom because he loved complaining about how he was trapped, and had no way out. He LOVED losing. He loved suffering. He loved overeating and then hating himself because he was fat. He loved having an excuse for not doing anything. What he really loved most of all was talking in a restaurant while somebody else was paying attention to him and paying for his meal. At least he sort of understood that:

“Sloth in writers is always a symptom of an acute inner conflict, especially that laziness which renders them incapable of doing the thing which they are most looking forward to . . . To accuse writers of being idle is a mark of envy or stupidity…”

Excuses, excuses, excuses. The whole third part of Enemies of Promise is an autobiography showing how Cyril Connolly was doomed to fail in life even though he had literally every single thing going for him to ensure his success as a writer except maybe good looks and an aristocratic family. He even had talent. He was intelligent. He had the best education money could buy, and once he got married he had no worries about anything. But any time he got close to a real achievement, he choked. He wanted failure. He hated himself too much to succeed.

You should put together a Cyril Connolly reading group with your friends. You can read parts of The Unquiet Grave and Enemies of Promise out loud to each other and you’ll learn a lot about writing. But the main reason to read Cyril Connolly is to figure out where he’s going wrong, and where he’s lying to himself or just making excuses for not doing anything. You have to learn how to not be Cyril Connolly, and it’s harder than it sounds.

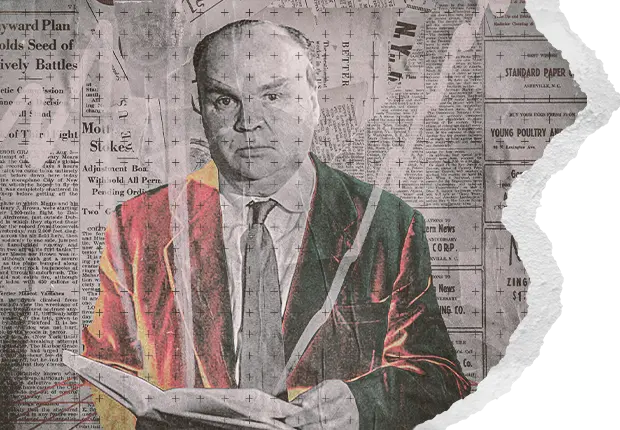

Look at his fat, ugly face. Do you really want that to be you too? This is what will happen to you if you walk around telling people you’re a “writer”, and go to parties talking about writing, and live the whole “writer’s life” thing and never actually do any writing. You know people like that, and they’re not as good at it as Cyril Connolly was.

We need a new Enemies of Promise now. Not a flowery piece of self-pity, but a practical guide for us, and for you, in this world right now, not in 1938. We need to understand how to create work that’s going to last, and we need to understand how to protect ourselves from becoming failures. We need to build a future where we can win.

“There is but one crime,” Cyril Connolly says: “to escape from our talent, to abort that growth which, ripening and maturing, must be the justification of the demands we make on society.” You see, he’s not always wrong. But we need to teach ourselves how to find out what’s good in a writer like Cyril Connolly and what we should just ignore. Otherwise we’re all in danger of becoming Latin teachers and I hope we have more self-respect than that.