Fully Automated Luxury Agonism

Some time in the late 22nd century, one of the great men of Mars decided to marry his daughter away. She was said to the best of the Martian women, who were famed for their beauty throughout the solar system. On the appointed date, in the shadow of Olympus Mons, in a great dining hall constructed especially for the purpose, 12,000 suitors were gathered. The best young men of all the great houses were there. It was the old man’s desire to put them to a series of tests—physical, mental, moral and artistic—to find the best eugenic match for his fair daughter. The tests would last exactly 687 days: the length in Earth days that it takes for Mars to complete one full orbit of our sun. And then, finally, the groom would be chosen.

During the feast to inaugurate the spectacular contest, the preferred candidate, a man of high birth and distinguished political career, disgraced himself by becoming drunk and dancing on his head on the enormous banqueting table…

*

Despite over a century and a half of catastrophic setbacks to the cause of national and global communism, we are still, even now, being told that the future belongs to the ideas and the heirs of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. All the failures of theory to translate into reality, all the blood and tears and suffering, the counter-revolutions and the collapse or disappearance of the Soviet Union and every communist regime except North Korea have done nothing, apparently, to dissuade the fanatics from believing that the final revolution of the working classes is not only good but also inevitable.

No, Marxism isn’t wrong, a botched theory that should be abandoned once and for all. Instead, we are told, Marxism was simply too far ahead of its time. Although Marx and Engels could see the future, they couldn’t quite see it clearly enough to predict when the dialectic would reach its final synthesis and catapult the world beyond capitalism and into communism.

Aaron Bastani, the hamburger-headed author of Fully Automated Luxury Communism, likens Marx and Engels to John Wyclif, the English priest whose heresy foreshadowed the Reformation a hundred years later. What distinguished Wyclif the failed revolutionary from Martin Luther the successful one was technology, plain and simple. The two men basically shared the same views about the Church, its hierarchy and its theology (this is true), but Martin Luther had access to the moveable-type printing press and John Wyclif did not. This medieval equivalent of the internet’s information superhighway allowed for Martin Luther’s polemics to be spread widely and easily and prevented the authorities from suppressing them like Wyclif’s writings had been. And so the Reformation began in Germany in the sixteenth century and not in England in the late fourteenth.

Today, according to Bastani, we are approaching the eve of another “moveable-type” moment, when Marx and Engels’ ideas will finally come of age and acquire the technology that will, at last, make them feasible. Bastani calls this approaching watershed the “Third Disruption.” The First Disruption was the Agricultural Revolution, which took place in the Near East about 10,000 years ago and saw the emergence of the earliest agricultural states, which used fixed-field farming and the domestication of livestock to build urban settlements whose like the world had never seen before—civilisation as we know it was born. The Second Disruption, which began only a few centuries ago, was the Industrial Revolution, when the invention of steam-powered machines allowed us for the very first time to exceed the brute power of beasts of burden, transforming our productive capabilities and the way we live just as much as the invention of farming, if not more.

But it’s the coming Third Disruption that will prove the most transformational of all, because it will abolish those factors that motivated humans to strive towards previous Disruptions—scarcity and want—as well as the social structuring—the hierarchy of haves and have-nots—that was essential to make all previous forms of civilisation work, however imperfectly. Full automation, limitless renewable energy, endless natural resources derived from asteroid-mining, and new technologies like genetic editing and lab-grown food will release us from the duty to work to survive and the need for anybody to have more or less than anybody else. This situation of “extreme supply,” of inexhaustible information, resources and labour, will undermine the whole edifice of capitalism, destroying two of its central presuppositions: that scarcity is unavoidable, and that things will cease to be produced if the marginal cost of producing them falls to zero.

For a time, perhaps, the powers-that-be will resist the Disruption, creating situations of artificial scarcity to justify the continuation of the present regime, but ultimately any such attempts will prove as futile as present attempts to censor and control the internet. Under conditions of extreme supply, “fully automated luxury communism” is all but a foregone conclusion.

That may be so. If the promise of unlimited energy, labour power and production is realised, then it may indeed be untenable for the world to be run as it currently is or ever has been. But that doesn’t mean that a new dispensation where everybody gets exactly what they want and need, for free, as a basic human right, will work or satisfy everybody in the long run. Quite the contrary, in fact. The prophets of “fully automated luxury communism” are ignorant of the real lessons of Francis Fukuyama (and behind him, Nietzsche), although they claim to know and understand them well.

Contrary to the way it’s generally portrayed, Fukuyama’s “end of history” thesis was not simply a triumphalist ode to the victory of liberal capitalism over the Soviet alternative. It was also a warning about the effects such a victory, and the unipolar world it ushered in, would have on our ability to flourish as human beings to our fullest capacity. The book Fukuyama’s essay became is called The End of History, but the second half of the title—and the Last Man—is usually forgotten.

The Last Man, a creature first identified by Nietzsche, emerges only at the so-called End of History, when the dialectic driving man’s historical progress comes to a stop. As Fukuyama explains,

“Nietzsche’s last man was, in essence, the victorious slave. He agreed fully with Hegel that Christianity was a slave ideology, and that democracy represented a secularized form of Christianity. The equality of all men before the law was a realization of the Christian ideal of the equality of all believers in the Kingdom of Heaven. But the Christian belief in the equality of all men before God was nothing more than a prejudice, a prejudice born out of the resentment of the weak against those who were stronger than they were…

“The liberal democratic state did not constitute a synthesis of the morality of the master and the morality of the slave, as Hegel had said. For Nietzsche, it represented the unconditional victory of the slave. The master’s freedom and satisfaction were nowhere preserved, for no one really ruled in a democratic society… For Nietzsche, democratic man was composed entirely of desire and reason, clever at finding new ways to satisfy a host of petty wants through the calculation of long-term self-interest. But he was completely lacking in any megalothymia [Greek for “the desire to be recognised as greater than other people”], content with his happiness and unable to feel any shame in himself for being unable to rise above those wants.”

Although Fukuyama saw the Last Man as a product of the triumph of liberal capitalism rather than Marxism, which at the time of writing appeared to have been confined to the dustbin of history, the Last Man would be just as at home, if not more so, in a society of “extreme supply.” There would be ample nourishment there for the Last Man’s unique spiritual disease. Because, at base, that is what the Last Man embodies: a rot of the soul which prevents man from developing his inborn desire to seek distinction through meaningful challenge, to cultivate what the ancient Greeks called thymos, which might best be translated as “spiritedness” or “warm-bloodedness.” In a world where everything is given to you, where your value as a human—ethical, economic and political—is the same as that of every other one of the billions of people who inhabit the earth with you, what place would there be for men who are not content simply to be part of the crowd?

For any man of passion, living in such a world would be stultifyingly boring. Pointless, even. One is reminded of Christopher Hitchens’ remark that he’d rather go to hell than heaven, because at least there would be interesting people to talk to in hell. As glib as Hitchens’ commentary on religion may have been, this remark strikes at the heart of the secularised, bastardised heaven-on-earths utopian socialists have been dreaming up for the last two centuries. The advent of extreme supply presents a dilemma, yes, but not the one idiots like Aaron Bastani think it does. With everything provided and nothing left to strive for, why go on living at all?

Why indeed.

So what, assuming we are about to end up in a world of “extreme supply,” would be the alternative to this smothering equality? What could invest life with meaning and purpose and make our existence worthwhile once again?

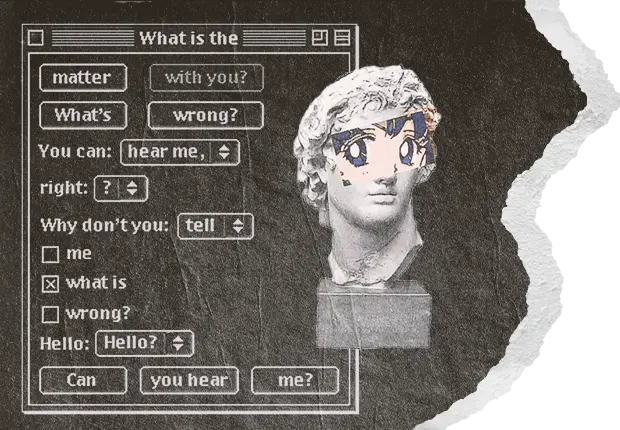

Agonism. Fully automated luxury agonism. Let me explain.

Agonism was one of the great discoveries of the pioneering Swiss classicist Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1897), who lectured at the University of Basel and was a contemporary and friend of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Burckhardt’s direct influence on Nietzsche, who would make agonism a central part of his philosophy, is clear. The two men maintained a lively correspondence for many years after Nietzsche left the university and began his peripatetic lifestyle. Burckhardt was one of the people Nietzsche wrote to during his decade-long period of “madness” before his death.

In the most basic terms, “agonism” refers to the Greeks’ distinctive mentality in which competition was pursued not just as an end in itself, but, in the words of a more recent scholar, “as the highest end available in human existence.” The archetypal form of the agon (the word from which “agony” and “antagonist” and “protagonist” derive) was the athletic contest, but the agonal mentality was, over time, extended to virtually every aspect of Greek life, to everything from poetry to politics.

Although there have been other societies that have championed athletic contests, such a fondness, by itself, does not indicate the presence of an agonal mindset. The Greeks did not simply view athletics as important or exciting. Rather, they believed that these “essentially useless” contests were more important than anything else and that victory in them was an achievement greater than victory in any other endeavour, including warfare.

To emphasise the ubiquity of agonism in Greek culture, Burckhardt cites the story of Cleisthenes of Sicyon, described by Herodotus in his Histories. Cleisthenes wanted to find a suitable groom for his daughter, and so he decided to invite suitors from across the length and breadth of Greece to compete against one another for this prize. The contests apparently lasted an entire year, and were used to assess the suitors’ abilities as athletes and musicians, as well as their general moral character. Similarly, Nietzsche liked to cite Hesiod’s Works and Days and its description of two different kinds of strife, one bad and one good. The good strife was the agonal mentality, which pitted everyone in society against everyone else. And Hesiod meant everyone. It wasn’t just athletes competing against athletes, or poets against poets: even beggars would compete among themselves for the prize of being the most skilled at begging.

Where did this spirit of competition come from? Burckhardt and Nietzsche both believed that it derived, ultimately, from a profound pessimism. The Greeks were aware, in the most fundamental sense, of the misery and suffering—the strife—that lie at the core of human existence. But instead of turning away from or denying that insight, the Greeks channelled their awareness towards forms of creation that affirmed the nature and value of existence. If all was, at base, an eternal procession of challenges, victories and defeats, why not direct that cycle towards a positive end—even if that end, ultimately, was destined to be impermanent, just like everything else?

According to Burckhardt and Nietzsche, agonism was the source of the Greeks’ immense creative talent. Because of the never-ending call to competition, the Greeks were constantly reaching for new heights in every area of their lives. Burckhardt called agonism “a motive power known to no other people—the general leavening element that, given the essential condition of freedom, proved capable of working upon the will and the potentialities of every individual.” Nietzsche likened the agonal process to the endless passing of a torch: “every great virtue sets afire new greatness.” And whereas today we might think that competition and rivalry have no place in the development of the arts, largely because we believe artistic creation cannot be “tarnished” by such “lowly” concerns as the artist’s prestige, the opposite was true for the Greeks, who according to Nietzsche, “know the artist only in personal conflict.” Agonism was a powerful stimulus to the development of totally new forms of expression including tragedy, comedy and choral lyric.

So if agonism can reenchant the harsh, disenchanted world of the ancient Greeks, endowing life with meaning and inspiring a cultural, political and artistic efflorescence that remains the envy of the world to this day, I think it could certainly do the same to a world rendered void by the excesses of “extreme supply.”

Of course, this new agonism wouldn’t be for everybody. There would be plenty, probably most of the planet’s billions, who would be content to collect their universal basic income and plug into their headsets for a life of VR porn and Marvel movies or whatever shitty superhero escapism is on offer. Only a minority would take up the challenge of agonism, but there would be absolutely no impediment to their doing so: freedom and equality, the two preconditions for agonism according to Burckhardt and Nietzsche, would both be there for anybody willing to take them and do something with them.

Agonism, like any social institution, had its downsides. It also had its strangenesses. Agonism in the world of “extreme supply” would be no different. As far as strangeness goes, what could be stranger than ostracising—i.e. banishing—people in the name of keeping the game going? But that’s precisely what the ancient Greeks did. Rather than functioning as a means to get rid of potential insurgents from the polis, as many historians have claimed, ostracism in fact served to maintain genuine competition when it was under threat, said Nietzsche. As we all know, a game ceases to be fun when a player becomes too dominant. This is even true for rats, as Jordan Peterson likes to remind us: scientists have shown that if two rats engage in play and one of them wins too many times, the other rat will stop initiating play altogether. The game is now over. In ancient Greece, when such a situation arose it would lead to the breakdown of the agonal spirit—with potentially dire consequences, as we’ll see—and so in order to keep it alive, the too-dominant player would have to be physically removed from proceedings.

Imagine a situation where a great sportsman is banished to one of the moons of Mars or even Jupiter, or the greatest musician of his day is sent away to an underwater city, deep in the south Pacific, built especially to house champions whose reigns had lasted longer than they should have… These things would be part of fully automated luxury agonism too.

On the whole, Burckhardt was less sanguine about agonism than Nietzsche was. While Burckhardt recognised agonism’s tremendous vital power, he also saw it as a source of great anguish and anxiety for the vast majority of its participants. He called agonism a “dark and demonic power, as dangerous as it is creative.” In a society organised totally for competition in every aspect of life, only a few would ever know the thrill of triumph, while the rest would be condemned to suffer the disappointment and shame of defeat. Even the victors, in time, would become losers too. Burckhardt illustrates this with a story from Pausanias about a certain Timanthes, a champion pankratist (the ancient Greek equivalent of a mixed martial artist) who discovered that his physical powers were on the wane. When Timanthes realised he could no longer draw his massive bow, he built a funeral pyre for himself, climbed on top of it and burned himself to death.

Nietzsche’s retort to Burckhardt was that the Greeks did not experience competition, including defeat, as we moderns do. We must imagine ourselves as the Greeks were, and they were, in many ways, radically different from us. Nietzsche believed that what mattered to the Greeks was not how one felt—elated in victory or jealous in defeat—but that one actually felt those things. Stimulation of the right impulses was what truly mattered. Indeed, the loser’s envy was actually seen as a positive force, because it drove on further competition. So positive, in fact, that the Greeks believed it to be “the effect of a beneficent deity”—a divine gift.

Clearly, modern man stands at quite some emotional and intellectual distance from the agonal spirit. It would take time, under the right guidance, for that spirit, motivated by the right impulses, to develop. Nietzsche identified three mechanisms that ensured primordial strife was given a stable form in agonism and held in place. Apart from the encouragement of rivalry and recognition that envy was a gift from the gods, most important of all was an institution to make the pursuit of self-distinction the highest possible goal in public life. This was the polis in its archetypal form. Citizens understood that they could do the polis no greater service than to achieve victory in competition. The polis was able to do this because the Greeks saw the city as a living organism, of which each citizen constituted an organ or appendage. So what was good for the individual was good for the whole, and vice versa.

Nothing less than a neo-polis, a political community dedicated to collective flourishing through individual excellence, would be enough to make agonism work again. Like ancient Athens, it would have its own constitution and its councils, as well as courts to punish transgressors. In time, it might also develop its own eugenic codes, just like the ancient Greek city states, to ensure that the best of the best mated with each other to produce the most exemplary specimens for entrance into the agon.

Any attempt to control primordial chaos and channel it towards productive ends is bound to be fragile, and agonism was no exception. The system, as we’ve seen, was liable to break down if competition ceased, making ostracism a necessary intervention. But ostracism didn’t always work, or it wasn’t used, and instead there would emerge a megalomaniac, a cruel debauched figure who would return the community to “that pre-Homeric abyss, a horrible ferocity of hate and desire to annihilate,” in Nietzsche’s words. Nietzsche uses the hero of Marathon, Miltiades, as a prime example of what could happen when an individual achieved too much distinction.

“Placed on a lonely pinnacle and carried far beyond every fellow competitor through his incomparable success at Marathon: he feels a base lust for vengeance awaken inside him against a citizen of Para with whom he had a quarrel long ago. To satisfy this lust, he misuses his name, the state’s money and civic honour, and disgraces himself. Conscious of failure, he resorts to unworthy machinations. He enters into a secret and godless relationship with Timo, priestess of Demeter, and at night enters the sacred temple from which every man was excluded. When he has jumped over the wall and is approaching the shrine of the goddess, he is suddenly overwhelmed by a terrible, panic-stricken dread: almost collapsing and unconscious, he feels himself driven back and, jumping over the wall, he falls down, paralysed and badly injured. The siege must be lifted, the people’s court awaits him, and a disgraceful death stamps its seal on the glorious heroic career to darken it for all posterity. After the battle of Marathon he became a victim of the envy of the gods. And this divine envy flares up when it sees a man without any competitor, without an opponent, at the lonely height of fame. He has only the gods near him now—and for that reason he has them against him. But these entice him into an act of hubris, and he collapses under it.”

In a future agonal state, we might expect to see emerge men whose cruelty and thirst for vengeance and self-exaltation will outstrip any Miltiades of the past, and perhaps even the greatest despots of history so far. Their campaigns of annihilation will stretch across the planet, the solar system, and maybe even beyond. The stars will burn red with blood and for a time such men will challenge the gods—but they too, like Miltiades, will be humbled and destroyed. The cycle of agonism will resume.

Despite the heavy cost of megalomania, the Greeks knew it was a price worth paying for the chance to affirm the nature of reality, rather than sink away from it in fear. The question is: can we do the same, or are we truly the Last Men?