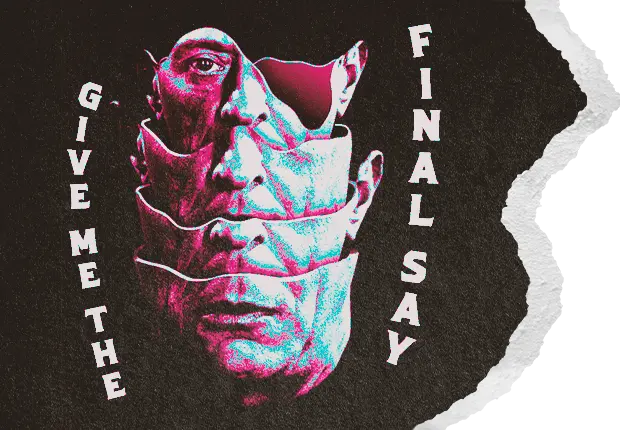

Give Me the Final Say

Bartholomew Grant was no longer able to sleep for very long. He called it a product of his old age and took it to mean that he should be up more in the mornings instead of laying for as long as he could in a kind of depression. And once he had started that as a proper habit again, he found that he still had some reserve of his old self that could work for him and find its way into trouble. Early on Saturday, then, as soon as it was considered polite, Bart dressed in his gardening gear and went out on the back deck to survey the yard. He pressed his weight against the banister where he felt his urine building and put his coffee down on the flat of the timber to let it cool.

The backyard climbed up the slope of the large hill. It was wide and dense with bush. Bart did not share a fence with his neighbours save for a few lines of wire that were more to draw them boundaries than anything else. The weeds were tall and they came right up to the house. Of a nighttime, something always moved in them, and it was getting to feel out of hand. The pathways were cluttered by hanging and fallen branches; dead palm fronds laid the grass flat beneath them, and some had begun to sink into the earth or gather nests in the petioles.

Down by the laundry, the back shed smelled of petrol and mulch and he breathed it in along with the iron heat when he opened the door. He took the garden gloves hung from the wall and smacked them against the deck to clear them of stiffness and spiders. As the morning sun began to burn sharp instead of cold, men pulled lawn mowers to life across the block that began a suburban call to prayer, all roaring far enough in their distance that they were as welcome as birds calling to mate or a kettle boiling. Whatever else they made weekends for, Bart took them for slow and honest work.

He went barefoot into the thickness of the yard and suffered the rocks under his soles while his skin hardened. With a rusty pair of cutters, he lopped the hanging branches along the path from the trunks of smaller trees. Brown sap stained the blades and caught a dull reflection of the sun at times. Some of the weeds grew out of the dirt with astounding sinew—they were almost young trees in their right, with branches of their own. He pulled them from the dirt at the very base and clumps of earth fell off the ragged roots or clung together when he tossed them in the pile. Some grew so thick he had to bend over with his cutters and gnaw at the roots two or three times before it gave way. His hands burned with a sharp ache. It felt good. He made sure to swap between his left hand and his right to be sure of gaining equal strength in both.

Along the wire next door, Margaret came down the hill with a laundry basket. Both said “Hello” but neither stopped just yet. He had found his stride under the sun as he began to hack away at the shade with the machete. He delighted in the fluid slash of his muscles. The bark cut away like flesh! Each time he ripped a branch away and added it to the pile, he turned and rested his hands on his hips and took the feeling in. As he got under the frayed palm on the hill, he heard a frightening sound slide over the grass and saw the small movements of it going away into the wilder parts of the bush, over next door, then out the back and into the crownland. He stood very still watching the grass where it had come from, and then he went back to work.

After an hour, Bart took his shirt off and let it hang over one of the branches he had cut along the path. When he went down by the back, he saw his reflection in the sliding glass door. The late morning looked good on him in the glass, his chest was bronze and leathery and the tan on his forearms accentuated his muscles. The dirt gathered around his ankles and in the hairs on his legs. He thought he looked strong. He did look strong. And he took up the machete again and held it by his side.

“I hope you know that you’re a foolish old man,” Margaret said over the fence.

“Why on earth is that?”

“Did you bother to put sunscreen on this morning?”

“For god’s sake, Marge. Leave me alone.”

“My boys are inside right now, not doing a thing. Why don’t you let me send them over?”

“Because I don’t want them around here getting in the way. Didn’t I tell you not to fuss over me?”

“Fine. But drink water, you fool. And make sure to yell when you collapse.”

“Okay, Marge. Thank you now.”

The palm fronds were long and heavy and he gathered them up so their bases curved together over his shoulder. He dragged them like Christ must have for a long way down the path. It was around that time he must have twisted his ankle, but he did not notice any pain until much later. He threw everything down in a massive pile and brushed the dirt off his chest. It streaked in his sweat and caused him to itch. He drank from the hose and washed himself. That gnarly old scar down the middle of his stomach seemed inflamed; it was sensitive to harsh matter over it, even certain fabrics he wore. In the reflection, his hair was long under his ears and flat against the slick of his forehead. He went with the rake and cleaned up all the bits of grass and the sticks he had left behind and softened the dirt over in the garden beds, then he gathered up all the refuse in handfuls and put them in the green waste bin.

He started up the whipper snipper, laid across the floor of the shed, for the first time in a while, reading the instructions on the two-stroke oil mixture while the corner stub of his cigarette stung his eye. He snipped along the walls and the fence lines, the base of trees, the overwhelmed gardens beds, through stubborn thickets, and then went along with a spray of poison from the gun where he felt the cause was lost. Finally, he took the old push-mower out over the rocks and the big spots of terrain; really, it had no business being out there, the blades chipped horribly against the sounds underneath, but it took the remaining thickness out of the floor of the yard and dealt with leaves and sticks he would rather see gone. Once he had shut it off things became very quiet in the numbness of his ears. Birds lost through them that he could hear somewhere. He walked down the garden path, now wide open and clear, and stopped for a moment under the shade. Margaret’s garden sprinklers switched on at midday and he let the mist blow and rest against his back until it was enough to make him feel cold.

It was the afternoon when he went back on the deck. He threw the full cup of coffee over the side and it bounced in globs of water and turned up the dry dirt that rested on top of its stain. His arms were spread on either armrest and his belly was open to the sun. Bart closed his eyes and leaned back and dozed. The sun was rather hot, and it overwhelmed him in a physical sense that, while certainly unhealthy, caused his blood to vibrate pleasantly around the edges of his eyelids and light long, warm sensations down his back. He knew how much of it he could handle; he maintained a sense of things as he slept.

John came around after some time and climbed up on the deck with him. Without asking, he got them both a beer from the back fridge and sat down next him.

“Did my boys offer to give you a hand today?”

“No, mate. I told Marge not to send them.”

“I see.”

“Tell her pardon from me, would you? I was cross with her today.”

“She’s fine. Was she pestering you?”

“Trying to help. But I’d like it if I could be left alone about that.”

“Yes I know. We said we would. She worries, though. Nothing’s going to change her.”

The phone rang from inside. John made to get up for it.

“Don’t do that, John.”

“Something wrong?”

“It’s probably Mark. I’m tired of him calling.”

“Right.”

“Long calls every afternoon to say nothing. Wants to hear from me, he says. Going to come around and get something done. I haven’t seen him once. Not that I want him here, mind you. But my number’s like a sounding board for him. I can’t bear to listen anymore.”

Bart may have dozed again. Gum nuts fell on the shed every so often. The condensation dripped through the table onto his leg, and the afternoon seemed to have fallen through the trees and behind the hill. It shaded the yard in soft, grey light. The way the sweat dried in his hair caused it to turn it up on the side and he noticed John was eyeing the long scar in his scalp. John startled when Marge called him for tea, her voice sounded impatient. He offered a place for Bart but he declined. They shook hands, customary for them, as old men, and Bart sat for a little longer on his own.

He was about to head in slowly and prepare a meal when a set of headlights illuminated the car port under the house, winding through the slats over the grass, and coming the whole way up the drive. While the car idled, he went through the house to meet the visitor. A familiar stillness waited for him indoors. It was nice to pass through. And gave him the confidence of his own home when he opened the front door to find her coming up the stairs. She was pleased to see him. She kissed him on the corner of the mouth and he made sure to hug for as long it suited a daughter.

“It’s good you came. I was about to start tea. Do you want something?”

“Don’t worry about me. I’m actually on my way home.”

She touched his shoulder without really thinking. Comfortable by him.

“I was worried you might have been Mark.”

“That’s not funny, Dad.”

“Oh come on.”

“He wants company, and he has no one else.”

“He’s miserable and he doesn’t do a thing to change.”

She looked through some of his drawers in the kitchen, clearly inspecting for something, so he didn’t ask. There was that haughty attitude she had lately that made it clear she was caring for him—the way she insisted on attending his appointments with him. She sometimes instructed him to eat, rest, drink water etc. Of course it was also playful. He knew she liked it and meant well by it, but it could be tedious sometimes when he wasn’t in the mood to humour her.

“Mark’s the kind of person you have to go easy on.”

“He’s had everything his whole life.”

“I don’t know, Dad.”

“And full of empty promises. I can’t entertain him any longer. He was meant to be over this summer to do my lawn for me—well, he was happy to pat himself on the back for that, then I never saw him. Had him in tears over the phone instead.”

“I think he tries.”

“Try? For god’s sake. You just get out there. I’ll show you.”

He brought her onto the deck and showed her the yard. It was clear and expansive under the early evening, the fumes of work still hung in the air alongside the fibre of paperbark and pine. Pile of branches strapped up and pulled under the deck. The shed door was wide open and latched while the mower sat out to dry after a wash.

“This is so irresponsible,” she said. “You realise this could kill you?”

“Here I am. Alive. Tell Mark about it.”

“He’s struggling. And so are you by the looks. You’ve got a death wish. This is a day’s work for a young man.”

“So tired of hearing that. Do you know every person in my life—”

“You piss and moan about being left alone like it won’t ever happen. I can go right now if you want. We all can.”

“John and Marge at my door every night. Kids of theirs singing over the fence. I can’t dress without someone knocking at the window. Well so your mother’s dead, we had a long time to prepare for that. And I cry just fine, by the way. I’m not repressed. I do it in private because I take it seriously, well then the neighbours heard me and they called an ambulance. I mean for god’s sake.”

“People need to adjust to you. You were gone a long time. You should be grateful to them and try to forgive the fact they care.”

“They to want to help? I want it back to normal.”

Bart began to cry. He tried to stop the early sob but it caught in his throat and mixed with his spit. It made him sound pathetic. He coughed into the collar of his shirt. He wiped his eyes very hard to try and get away from it, but she approached him with her arms out and a pitying smile. Young women found it endearing when old men cried, and it made him angry. He smacked her hand away so hard that he felt her ring against the back of his hand and she shouted in pain. She steadied herself on the kitchen bench and looked at him in disbelief.

“Don’t come to me like that. I hate it when you do that.”

She was holding her hand. About to cry herself.

“I guess I’ll tell Mark what you really think of him then. That way we can all leave you alone.”

“You can tell Mark to fuck off over himself. That goes for you too. Now go on, you should be getting home.”

He watched her headlights recede across the yard again while he sat on the deck. The car sped away under her foot, angry. Well, so was he. Before his wife had died, John and Marge would often visit them and spend hours under the yellow porch light outside. Food and drink piled up over the outdoor table, no coasters, and it was still stained with them. He felt the weight of his beer back and forth in the tin. Now that it was him alone, it seemed as though he only saw John or Margaret, and never the two of them together. He thought, whether they realised it or not, that that must be intentional on their part, to preserve what they had shared together as a group. Their kitchen window sat over their pool and he could sometimes see their old faces pottering back and forth in the white fluorescence behind the glass. If John was ever tender with her, he watched. On the other side of the deck, the young couple’s house came up incredibly close to his. They were always fighting with each other. It was the mundane kind of bickering that generally ended up being something more. She would often yell at him to get out of the house, not meaning it seriously. He liked them anyway. People had their own normal. The young man often waved to him and, although she sometimes tried to avoid him, the woman came over one afternoon to warn him the police had been around looking for someone, and that he should make sure to keep his door locked.

The young couple had friends over that evening. He could hear everything they said. Most of them brought children of their own who strayed in and out of his backyard at its far end where the fence wire had collapsed. Bart didn’t mind—he was glad they could, now the long grass was cut. Their parents called to them to be careful but never chased them farther than the edge of their seats. He listened to the guests for a long time in the dark. The mosquitoes began to bite him on the neck but he brushed them away. Much of it was familiar to him. The early notions of families who have begun to take themselves seriously: home ownership, tax fraud etc. They permitted themselves to express racist feelings, to discuss anal sex and its frontiers, gossip of their peers, reality television, sporting leagues, local matters as they seemed relevant. He cooked under them, laughed with him, and counted them, that night, as his old friends, the same as the rest, though they never thought of him there. By the end of the night, he was barely ready to turn in. Nor did the children seem to be—lost in the wilderness of the Castle Hill and bringing their parents down to have to find them and carry them inside. Long goodbyes, short ones, those who lingered by the front, in the gravel, one foot in the door of the car.

Later on, before he went to bed, he took the rubbish out to the bin and found the man from next door doing the same. His bag rattled with glass bottles, and Bart’s smelled of scraps and potato peels.

“Hello Bart.”

“You were having a party.”

“Friends of mine from work. I hope we didn’t disturb you?”

“It’s the most fun I’ve had in weeks.”

“You know I’m so sorry—I should have asked you around.”

“Not at all. The young should stay that way.”

“I saw you out there today. You’re looking good.”

“Feel good. I’ve been trying to find the strength lately. Trying to make a start… My wife passed, I’m not sure if you noticed. Spent some time after in the hospital, too…”

Bart turned the scar on his head and pulled his hair back.

“I noticed. John told me. I’m sorry I haven’t said anything. You seemed okay. I wasn’t sure whether to bring it up.”

“You were right not to.”

“My old man he had a similar thing, you know. He didn’t want to rest. He worked his whole life so he didn’t have much of a system outside that. It’s hard to say without sounding foolish. The doctor says rest, sure. I mean you know that’s true. But for some people… I guess we only know how to live one way.”

“I already died. I’m back from the dead.”

“Well in that case maybe you don’t do the same things you always did.”

“My daughter said something like that.”

“I can see it both ways.”

“I was starting to, as well. But after today.”

“Listen if you ever need a hand just sing out.”

“Thank you, mate. I will.”

Bart couldn’t remember the man’s name. He shook his hand when they parted. Once inside he locked the doors and laid in bed. Beer at the back of his mouth he couldn’t bring himself to wash. Everything ached—all in ways he had not yet determined. The shower was running next door, their voices echoed over the bathroom tiles, he heard them. She was laughing, yelling: “Don’t!” That inimitable sound. He wanted to listen to them. Find his way into their lives. But he was lost to sleep before long and some part of his old life that found him. Chasing your wife nude in the privacy of your own home. He was alone at the dining table while his children played downstairs. Mark crawled under the chair after his sister. John and Margaret seemed to arrive. And Mick, who had died, Isaac, Henry, it was not strange to see them, he still dreamed of his parents and high school teachers who were all long dead, as well, bringing him into the office and sending him home without clothes. God, tedious! The paper thinness of his dreams that told him too often he was dreaming, stopped him from ever believing something deeper than what it was. Her hand rested on the dining table. Naked as though he had chased her. Dress, darling. Don’t let everyone see you. She was fond and smooth and seemed as young as Mick was and he feared they had fallen in love without him around to see to her.

“You’ll need to mow the lawn tomorrow. I’ve friends coming.”

“Yes I did already. Go and see, it’s quite nice out there.”

“Just have it done in time.”

“It’s done.”

“By the fifth of the month at the latest.”

“Hey, listen. I did. I did and you’re not listening.”

When he put his hand on top of hers, it fell through to the table. He pawed at her again and again, slowly realising the texture of his linen. Oh for god’s sake! Such an empty sort of dream. Dreaming like that. His eyes adjusted slowly, there was a candid sense of what was real and what was not, some of the furniture from that dining room being slow to fade, giving way to the blue sheets of his bed, and his wife as she folded back into the dark shapes of his room. Everything was just as lost to him in the ways he had always known. He knew that and felt ashamed for wishing otherwise and he needed extremely to piss which only aggravated him more. All false and forgotten but for his hands which had been the same. They both had come with him into either realm. “You take your hands.” If that was wisdom of any kind. His right hand lay open on the top of the bed, as it had on the table, illuminated by the streetlamps and the moon outside. He felt that it was slow to open and close, and sunburnt as his skin wrinkled against itself, old and unresponsive, he reached for the dark to find something to grasp, there being nothing but himself, his left. He clasped his hands together and rested them on his chest and he slept again for a few hours until he woke around early dawn while most others were still sleeping.