I Like Poking around in Sewers, Seeing What I Can Do about Justice

Lloyd Hopkins is the type of cop who can only exist in fiction. More specifically, Lloyd Hopkins is the kind of cop who can only exist in the fiction of James Ellroy (1948- ). A Los Angeles native, the son of a murdered mother (case still unsolved), and a high school and army dropout who apparently once joined the American Nazi Party, Ellroy transformed himself from a low-level hood and peeping Tom into the undisputed king of American noir fiction. Most critics and readers laud his Underworld U.S.A. Trilogy—American Tabloid (1995), The Cold Six Thousand (2001), and Blood’s a Rover (2009)—as the apex of his powers. In these books, mid-twentieth century American history, from the Kennedy assassination to Watergate and the FBI’s war against black militancy, is incisively examined via staccato prose and a harder-than-titanium outlook, especially concerning the reality of power and conspiracies in politics. These are the novels that truly won Ellroy the love of the high-brow set. Even despite his self-professed right-wing politics (which, in this humble writer’s opinion, is all an act), Ellroy is the type of noir writer whose name you can drop at Boston or New York cocktail parties and not come off as a mouth-breather.

Blood on the Moon (1984) was published well before Ellroy escaped the mass market ghetto. The novel’s detective, the aforementioned Hopkins, is an odd duck. Driven by what he terms his “Irish Protestant ethos,” Hopkins is an LAPD sergeant who stumbles into a sixteen-year string of homicides in Los Angeles County. The deceased are all young white women who are a kind of plain-attractive: bookish, reticent, and, most importantly, alone in the teeming sewer of Los Angeles. It is Hopkins who uncovers the reality of these crimes, many of which were initially labeled as either suicides or strange accidents. His investigation uncovers a lifetime’s worth of filth: a high school rape in 1964, a male prostitute working for a corrupt sheriff’s deputy, and a serial killer with a twisted fixation on a betrayed Irish Catholic girl, Kathleen McCarthy, who grew up to become a rage-filled feminist poet and bookstore owner. Hopkins embeds himself in this misery. He sleeps with Kathleen, he nudges the sheriff’s deputy towards suicide, and, in the novel’s denouement, he exchanges gunfire with the serial killer in their old neighborhood of Silverlake.

Lloyd Hopkins is a hero, to be sure, but a complicated one. Although he espouses his Irish Protestant ethos, which essentially boils down to protecting innocence at all costs, he is a serial philanderer, a user of recreational drugs, and a murderer. The first part of Blood on the Moon takes place during the infamous Watts Riots of 1965. On Wednesday, August 11, 1965, Lee Minikus, a motorcycle officer for the California Highway Patrol, was flagged down by a pedestrian concerned about a white Buick driving erratically on Avalon Boulevard. This was in Watts—a predominately black part of Los Angeles that had a tense relationship with law enforcement. This animosity exploded when twenty-one-year old Marquette Frye and twenty-two-year old Ronald Frye were pulled over at 116th and Avalon. Officer Minikus smelled alcohol in the car, and when Marquette, the driver, failed to produce a driver’s license, a field sobriety test was ordered. Marquette failed. Things remained generally cordial until Marquette’s mother arrived at the scene and started chastising her son for his habitual imbibing. Marquette responded to this dressing down by reportedly shouting, “You motherfucking white cops, you’re not taking me anywhere.” This loud outburst, along with the hot weather and the already strained racial tensions of the Civil Rights era, helped to set off a five-day riot that would claim thirty-four lives and millions in property damage.

Hopkins is a simple private first-class in the California National Guard when his unit is called into the Watts maelstrom. Here, after trying to give a decent burial to a dead wino, Hopkins finds a superior—Staff Sergeant Beller—delighting in the wanton slaughter of Watts residents. Beller drops the “gamer word” frequently. He, like Lloyd’s older brother, who is responsible for Lloyd’s prepubescent rape by a deranged derelict, is the personification of far-right American politics. Beller blames blacks, Jews, and communists for America’s decline. His politics are exorcized by Hopkins, who uses a machine pistol to decapitate Beller outside of a portable toilet. As for Lloyd’s older brother, he is beaten and humiliated after Lloyd takes weapons from his prepper’s cache. Such clues reveal Ellory’s true politics (see also his first novel, Brown’s Requiem, which has as a villain a Nazi-loving golf caddy who is guilty of incest), as outsized right-wing caricatures always get chewed up and spit out in his oeuvre.

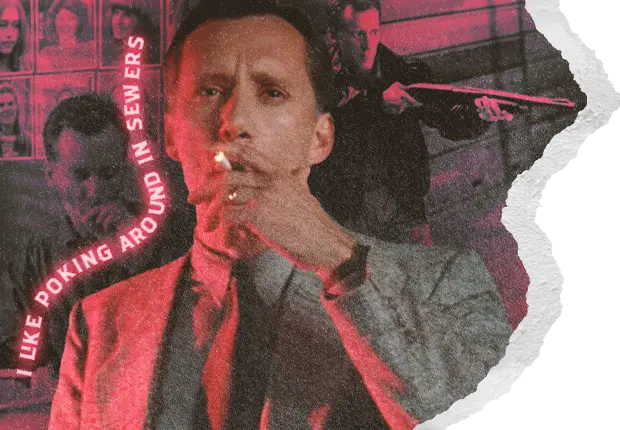

Speaking of politics, James Woods is not one to shy away from expressing himself. Mr. Woods is among the few openly conservative actors in Tinseltown and has likely suffered because of it. In 1988, Woods’s opinions were less well known, or at least less publicly known. In that year, Woods co-produced an adaptation of Blood in the Moon simply entitled Cop. Woods stars as Lloyd Hopkins, and his portrayal exudes the same type of manic energy that comes across clearly in Ellroy’s novel. Woods’s version of the character speaks a mile a minute, and his investigations are fueled by limitless coffee and cigarettes. Woods also nails the cerebral aspects of the Lloyd Hopkins character. Described in the novel as a kind of “boy genius,” Hopkins is a gumshoe just as comfortable in the field as he is in a library. Woods spends a significant chunk of Cop pouring through crime reports, studying crime scene photographs, and conducting interviews that are superfluous. Why superfluous? Because Hopkins already knows the answers because he’s that brilliant.

Woods’s version of the character also has many of the same warts as the Ellroy original. The married Hopkins sleeps with a high-end prostitute (played by Randi Brooks) and the feminist poet Kathleen (played in the film by Lesley Ann Warren). He tells his very young daughters graphic stories of burglaries, rapes, and homicides as twisted bedtime tales. He uses not-so-inclusive language, such as referring to West Hollywood as “a faggot sewer.” However, the Lloyd Hopkins of Cop does not have a conspiracy-theorist brother, did not kill a man during the Watts Riot, and was not sexually assaulted as a youth. Still, Cop is exceptionally faithful to its source material, barring a few scene swaps and extra murders. Director-screenwriter James B. Harris made sure to lift entire pieces of dialogue from Blood on the Moon just to please the book snobs. Ellroy obviously gave his blessing to Cop, and yet the author has never said too much about the oft-overlooked film.

And one could call Cop forgettable. Such an opinion is wrong, of course, but it’s not irrational. The film is a tough, neo-noir police procedural that came out during the heyday of lighthearted buddy-cop blockbusters. Cop feels nothing like Lethal Weapon (1987) or Tango & Cash (1989), both of which made beaucoup bucks at the box office by mixing crime with laughs and absurdist levels of action. Cop does not even feel spiritually similar to the far more serious Cobra (1986). Yes, both films do indeed make a point about the need to use excessive measures against criminality. And yes, both films focus on the heroism of renegade cops who attack the system in order to achieve justice. The difference though lies in the endings. Cobra sees LAPD detective Marion Cobretti (played by Sylvester Stallone) triumph against the Night Slasher (played by legendary ‘80s character actor Brian Thompson). This victory decisively ends not only a string of homicides in Los Angeles, but also destroys the Night Stalker’s strange vitalist cult of axe-wielding neo-fascists. No such sense of finality exists in Cop. After cornering the lovesick serial killer inside of his old high school’s gym, Hopkins unloads buckshot from his sawed-off shotgun. The killer dies, and yet Hopkins is still suspended from duty owing to his inability to play ball with the big brass. He is still on the verge of a divorce. And, most importantly, the death of one serial killer is not the end of all crime in Los Angeles. Then again, the execution is set-up with easily the hardest line of dialogue in the history of cinema: “The good news is you’re right: I’m a cop and I gotta take you in. The bad news is that I’ve been suspended, and I don’t give a fuck.”

Three shotgun blasts and Cop is over. The credits roll. The audience goes home. As an adaptation of Ellroy, Cop does not have the cultural power of L.A. Confidential (1997), nor does it accurately capture the alluring sleaze of Los Angeles, which is such a major part of Ellroy’s work. However, Cop is emblematic of Ellroy’s early, more inchoate era where the future maestro of L.A. noir wrote about serial killers, drugs, and other concerns of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Cop does get one thing right, and that is the immortal truth that bad men are necessary in order for good men to prosper. Lloyd Hopkins in the movie and novel is not a good man in either the secular, rule-of-law sense or the Christian sense. He breaks laws and breaks hearts, and yet, in the end, he is righteous. He alone discovers the killer, and he alone ends the killer’s iniquities. Like Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callaghan and Rust Cohle of the Louisiana State Police, Hopkins believes in the maxim that “the world needs bad men” to keep the other, even worse men from the door. This idiosyncratic morality is a large reason why detective fiction remains such a fixture in American culture. Since the days of Black Mask, Americans have loved crimefighters who go against the law and the idiotic bureaucratic system in order to get their man. That’s the spirit embedded in everything from Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler to Dirty Harry (1971) and Cop. And now that respect for the law is at its lowest point in recent memory, more and more everyday Americans will clamor for outlaws, rogues, and other off-kilter personalities so long as they prove capable of keeping the other bad men at bay. This mentality explains the Trump phenomenon, especially his still-improving poll numbers despite his recent conviction. This mentality is not going anywhere. Those resisting it would be better served making peace with Lloyd Hopkins and others like him who poke around in sewers in order to keep the normal world clean.