I’m Afraid You’ve Misjudged Me

In his lecture “Léon Degrelle and the Real Tintin,” Jonathan Bowden noted a curious tendency in modern portrayals of heroic characters, whether in films, writing, graphic novels or comics. While it still remains possible to depict heroes who embody some of the most important values we might recognise as distinctly right wing—Bowden calls such heroes “right-wing existentialist figures”—almost invariably these men come into conflict with opponents who are even more right-wing than they are. The bad guy is pretty much always far right. Never left or far left. Bowden calls this an “interesting trick.” It is.

In a democratic age, where equality is the highest value and the general creep, for that reason, is ever leftwards, there’s an inherent danger to any depiction of characters who possess singular strength and virtue. In their actions and their very being, these men offer the ultimate rebuke to the ideals of the day and the pencil-necked lesser men who enforce them.

Writers of the left, says Bowden, are only too aware of this danger, especially in genres like fantasy and pulp. The danger, that is:

“of subliminal Rightism in much fantasy writing where you can slip into an unknowing, uncritical ultra-Right… attitude towards the masculine, towards the heroic, towards the vanquishing of forces you don’t like, towards self-transcendence, for example.”

So there must be some way, some form of distancing device, to prevent the viewer or reader from identifying too readily with the hero and the values associated with heroism—with the real right, that is. Here’s where the “interesting trick” comes in handy.

The trick is why Red Skull, Captain America’s nemesis, isn’t actually a Red. He has a red skull, sure, but he’s a fascist, clear as day. His plans always involve the creation of newer, better robots and creatures to help him take over the world, the pursuit of perfection, in however a twisted form, rather than building a coalition of human trash—of freaks and layabouts and deadbeats and junkies and pimps and pedophiles—and unleashing it on society, which is what a bioleninist Red Skull would do. Although Captain America is basically the Aryan ideal of the “blonde beast”—“this enormous blond hulking superman with blue eyes,” as Bowden puts it—he “needs” Red Skull to prevent him from realising the true potential of his own biological supremacy and the values that are immanent to it. Democracy demands it must be so.

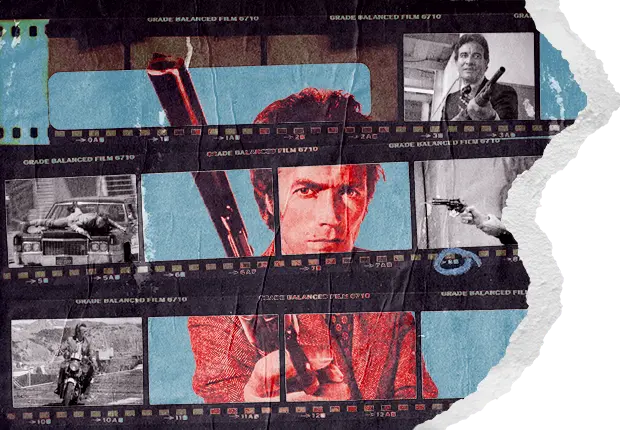

In the lecture, Bowden notes how Clint Eastwood “plays individualistic, survivalist and authoritarian” figures who are “always at war with bureaucracies and values that are perceived as conservative.” While there are plenty such characters to choose from, Bowden clearly means Dirty Harry in particular.

Bowden has no more to say about Eastwood’s films than this, which is surprising, because the second film in the Dirty Harry series, Magnum Force (1973), contains what is probably the most blatant use of the “interesting trick” that’s ever been committed to film.

To understand why, it’s worth considering the reception of the first film, Dirty Harry, released two years earlier. Detective Harry Callaghan’s debut was subject to hysterical accusations for its portrayal of a hardbitten, hard-pressed cop who will do whatever it takes to protect the people of San Francisco from a maniac killer—including the use of racial slurs.

Esteemed critic Roger Ebert certainly didn’t mince his words, describing the film as “fascist.”

“It is possible to see the movie as just another extension of Eastwood’s basic screen character: He is always the quiet one with the painfully bottled-up capacity for violence, the savage forced to follow the rules of society. This time, by breaking loose, he did what he was always about to do in his earlier films. If that is all, then “Dirty Harry” is a very good example of the cops-and-killers genre, and Siegel proves once again that he understands the Eastwood mystique.

“But wait a minute. The movie clearly and unmistakably gives us a character who understands the Bill of Rights, understands his legal responsibility as a police officer, and nevertheless takes retribution into his own hands. Sure, Scorpio [the film’s villain] is portrayed as the most vicious, perverted, warped monster we can imagine—but that’s part of the same stacked deck. The movie’s moral position is fascist. No doubt about it.”

But Ebert can’t have been too bothered by Dirty Harry’s “fascist moral position”: he gave the film a solid three stars out of five.

Pauline Kael, a critic known for her level-headed opinions—she dubbed Charlie Chaplin’s 1952 film Limelight “Slimelight”—really was bothered, though. “Fascist medievalism has a fairy-tale appeal,” she wrote in her review for The New Yorker, intending the reader to be in no doubt about just how fanciful and regressive the film is.

Dirty Harry is a “deeply immoral film,” says Kael. Why? Because it suggests that criminals—not socio-economic factors—commit crime, and that the answer to crime is to pursue criminals and, if needs be, kill them, rather than pursuing compassionate interventions that make society a fairer place for all.

Why would we want to kill people if we could be nice to them instead?

As if to underline her point, Kael recalls how, as she was leaving the cinema, she saw a “pink-cheeked little girl”—the movie was rated “R”—turn to her father and say, “That was a good picture.” Of course, a child would say that, Kael explains, because children are taught that problems are as simple as slaying dragons. But the truth is “crime is caused by deprivation, misery, psychopathology, and social injustice.” So there. Stupid little girl. She’ll know better when she grows up, especially if she gets a college education like Pauline Kael did.

When awards season came round, radical feminists picketed the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, where the 44th Academy Awards were being held, bearing placards with slogans like “Dirty Harry is a rotten pig.” The film wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar; although its star was in attendance.

The accusations of fascism pissed Clint Eastwood off mightily. He went to great lengths to deny them, even describing Harry Callaghan, in a pretty bizarre metaphor, as a kind of walking Nuremberg Tribunal—a final extraordinary court for criminals who couldn’t be brought to justice by normal methods, just like the Nazis. The accusations still piss Eastwood off to this day, apparently.

In my mind, there can be no doubt that the negative critical reception of the first film—it was a big hit at the box office, though—was responsible for the entire premise of the second film, in which Dirty Harry pursues a group of vigilante policemen who’ve taken the law into their own hands and started executing criminals across the city. Dirty Harry may do things a little differently, he may be a “neanderthal” as one of his female adversaries in the first film claims, but he’s not a fascist—that’s Magnum Force’s message, loud and clear.

Magnum Force opens with a local San Francisco gangster leaving court after being let off on a technicality. As the kingpin’s car, loaded with goons, leaves the freeway, it’s pulled over by a traffic cop, who kills the men in the car at point blank, before fleeing the scene on his motorbike. Later, another motorbike cop arrives at a sleazy pool party, throws a bomb over the fence and into the pool and then opens fire with a submachine gun—no survivors; a notorious pimp murders a prostitute by forcing her to drink drain cleaner, only to be killed the next day by a cop, at a remote location; a drug boss is executed in flagrante, in his penthouse apartment, again by a cop…

Pretty soon it becomes clear to Callaghan that a secret death squad is operating within the San Francisco Police Department. The crucial scene, where the trick is played, takes place as Harry parks his car. He gets out and finds the three killer cops waiting for him.

“You ‘heroes’ have killed a dozen people this week. What are you gonna do next week?”

“Kill a dozen more,” replies the group’s leader.

“Is that what you guys are all about—being heroes?”

“All our heroes are dead. We’re the first generation that’s learned to fight. We’re simply ridding society of killers that would be caught and sentenced anyway if our courts worked properly. We began with criminals that the people know, so that our actions would be understood. It’s not just a question of whether or not to use violence. There simply is no other way, inspector. You, of all people, should understand that.”

“Either you’re for us or you’re against us,” says another.

Dirty Harry waits a moment, eyeing the three men, then responds: “I’m afraid you’ve misjudged me.”

Without another word, the vigilante cops ride away on their motorbikes.

The inevitable showdown is now inevitable.

One thing that stands out in all this is how Harry’s pencil-pushing superior, Lieutenant Briggs, turns out to be the leader of the death squad. As we discover, the members of the death squad are young, idealistic former special-forces soldiers who have infiltrated the police deliberately, but Lieutenant Briggs is a greyhaired old hand who’s been lingering in the department for decades, like a bad smell. It’s almost as if the film, tipping its hat to Pauline Kael, is trying to tell us that policing is always an embryonic form of fascist authoritarianism.

Briggs even says as much, as he forces Harry to drive to the docks at gunpoint for the finale.

“A hundred years ago in this city, people did the same thing. History justifies the vigilantes. We’re no different. Anyone who threatens the security of the people will be executed. Evil for evil, Harry. Retribution.”

In the view from Magnum Force, only a policeman who isn’t really a policeman has what it takes to police the police. So what does that say about the police? Maybe they should be abolished…

Magnum Force is anything but a reactionary film—unless, of course, your sympathies lie with the sensitive young men of the mannerbund-cum-death-squad. The modern viewer—or me, at least—is pulled in two directions at once by the way the city appears in the film and by knowledge of what has since become of it. Looking at Dirty Harry’s San Francisco, the idea that the place was a lawless hellhole, requiring methods transplanted from a Central America dictatorship to bring it under control, seems laughable. It would still have seemed laughable twenty years ago. Maybe even ten. But certainly in 1973 San Francisco was a paradise compared to the sewer of open defecation, drug use and robbery it has now become.

And it has become that sewer in large part thanks to ideas that lurk very close to the surface of Magnum Force.

If the killer cops of Magnum Force had been able to transport Harry Callaghan fifty years into the future of his city—like vigilante Ghosts of Christmas Yet To Come—if he could have been shown the absolute state of San Francisco in 2024, would his answer to their proposition in that parking garage have been a different one? I’m not so sure. The more I think about it, the more Harry Callaghan appears in the guise of an ur-boomer, tending to decline with carefully orchestrated half-measures, contingencies that, in the end, prevent younger, less compromised men from doing what really needs to be done. Even get them killed.

With men like Harry Callaghan, collapse is only, at best, deferred. And so here we are today.