Like Mice in the Attic

We live in an age of tyranny and seemingly inescapable despotism the likes of which mankind has never known. Cameras survey our every move, snitching babushkas lurk behind every street corner, your own children might report you to the media over your political views, your livelihoods are under threat of immediate termination should you dare march out of step with the current order. The powers that be loom over every part of the world, and those areas still “free” are ruled by despots just as cruel. “Freedom” exists in name only, a certain set of privileges that can be taken away at any moment. All seems hopeless, yet there is a way through the foul smog that suffocates the earth.

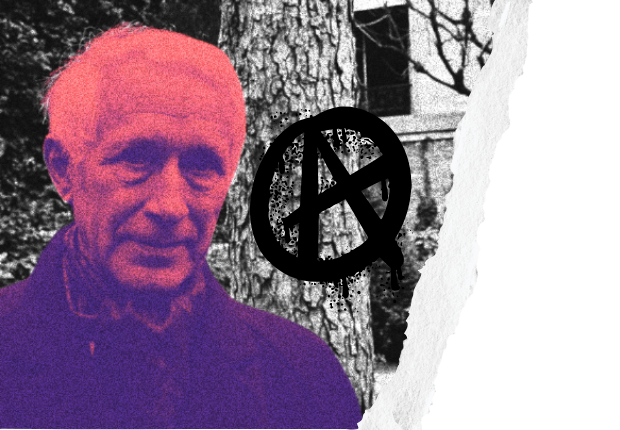

Ernst Jünger, famous for his WWI memoir The Storm of Steel, endured a long and successful life in silent defiance to the tyrannies of both Nazi Germany and the new Germany built at the sharp end of American and Soviet bayonets. Jünger lived as a dissident within both regimes: a man such as he, had no taste for any master but himself. It is in one of his final works, Eumeswil, that Jünger offers us a path through this new age of despotism.

In the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War, the world of classical Greece had been shaken to its foundations. New schools of philosophy questioned the very idea of what Greek culture was, the once-independent city-states had become lashed to larger Greek empires whose rulers looked on their fellow countrymen with sneering resentment in the aftermath of the war, and new powers in Carthage, Macedon, and Persia loomed on their frontiers like vultures circling a carcass. Greece was done for, and it wasn’t long before the half-barbarian Macedonians swooped down from their northern eyries to rule over the ruins. All of Greece, once a mosaic of independent cities and freedom, was now the subject of the lords of Macedon. Philip II’s shackles subdued the power of Athens and Thebes, leaving Sparta alone and isolated to die the slow death of irrelevance.

This changing world, beautifully captured in Nietzsche’s essay, Homer’s Contest, is not so different from our own recent history. The independent European kingdoms, carved by different Germanic tribes in the wake of Rome’s fall, developed and expanded to subjugate most of the planet through their colonial empires in the same way the Hellenes carved out their cities from the ruins of Minoa and expanded across the Mediterranean. Europe’s empires then clashed in a two-part war that spanned the entire earth, destroying themselves in the process. The half-barbarian Americans and Russians fell upon Europe like wild wolves to gobble them up in the same way the Macedonians fell upon Greece. What was left in the wake of both Macedonian and American rule was a world of despotism indifferent to the once proud and free peoples of Greece and Europe. The world after Alexander was ruled by his Diadochi warlords just as our world today is ruled by global oligarchs riding high off the spoils their forefathers won in the Second World War. Both the Diadochi and the oligarchs of today turned on their own nations to subjugate them with the rest of their new serfs. Look to the oriental despotism expressed in the self-stylized god-king, Cassander, something unheard of in democratic Athens only a lifetime prior to his occupation, for a vision of what the political order of the Hellenistic Age meant for the Greek heartlands.

Just what does this history have to do with Eumeswil? Those with a little knowledge of history might now recall that Eumenes, from whom Jünger derived the name for his fictional city, was one of Alexander’s Diadochi. Eumeswil as a setting is meant to represent life under such conditions as arose in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War and Alexander’s conquests, for that was the world Jünger found himself living in at the time of writing. West Germany, Jünger’s homeland, and once the heart of European culture, was, and still is, a mere vassal to the new American Diadochi. Today’s world is one of oligarchy and tyranny unthinkable in the West just a century ago, and we today live in the shadow of new Cassanders, who despoil our countries with their inflated sense of worth. The situation seems hopeless for us under the boot of this globe-spanning order, but Jünger offers us a means to freedom through this despotism.

To be an oligarch, a despot, or a god-king the likes of Alexander or Darius, this would be fine way to live. It is the ultimate dream of all life, to subdue the world under its own will. Yet we’re not all born into such roles, and it is harder still to grow into or take such power. The lords of the earth are uninterested in sharing their power, and their legions of deluded soldiers will defend them in the vague name of “freedom,” “justice,” or any other sort of manmade voodoo. How is it then that we who cannot prosper under the authority of any other man, but who have little to no power of our own, may find a suitable life in this world? Jünger answers this dilemma through his architype of the “Anarch.”

The Anarch is not an anarchist. He is not one who seeks to destroy all authority for the sake of global freedom or any such nonsense. No, the Anarch is not interested in suicide. The Anarch is a man out for himself, as Jünger poetically describes in this passage.

“The archaic figure of the mercenary is more consistent with the anarch than is the conscript, who reports for his physical examination and is told to cough when the doctor grabs his scrotum.”

One who takes up the internal mantle of the Anarch is one who casts away all serious loyalties to any entities that are not his own. The Anarch is an individual, even if that is only within one’s own head. Like a king in disguise amongst his people, the Anarch wanders the earth knowing his own secret station in life while others toil under others. He is a spy in service to himself, ready to disappear into the bush at any second should he become compromised, as Jünger shows through the character of Martin Venator and his hidden bunker in the wasteland. The Anarch is a man who does not take the world or life too seriously, for to do so would be to attach oneself to the petty dreariness of the dictatorship.

“Life is too short and too beautiful to sacrifice for ideas…”

Through the character of the Condor and Martin Venator’s brother, Jünger shows a world torn between two factions. Each despotic warlord seeks to overthrow the other and implement his own dictatorship. Amid this struggle, the Anarch has no care for the ideas of either regime. Venator lives as a man unconcerned with either side’s plight, for the fight is not his own, even though he works for one and the other is led by his family. Such a fight is beneath him, and he instead turns inward to cultivate himself and find some freedom through his service to the Condor and his own excursions into the wilderness.

“It makes no difference to me whether Eumeswil is ruled by tyrants or demagogues. Any man who swears allegiance to a political change is a fool, a facchino for services that are not his business. The most rudimentary step towards freedom is to free oneself from all that. Basically each person senses it, and yet he keeps voting.”

Jünger recognizes that there is no chance for meaningful change in the direction of a world that would ideally suit him. All he can do is persist as free as he possibly can be in his life while the powers that be kill each other. He will not waste his own time, resources, or life for a fruitless cause. Within his own life, Jünger saw no possibility of true political autonomy from the new Diadochi, and so he checked out of the stupid struggle that was the Cold War in favor of his own personal pursuits. One might say that he checked out of life, gave up the fight even, but in a world as hopeless at West Germany in the late 1970s, what could he have done but live as best as he might? His own dreams of the world would have to wait for another day, beyond his own lifetime, and his life’s works were dedicated to preserving freedom through the next century of tyranny.

The philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche spurred the reawakening of classical Hellenism onto the stage of politics in Germany. Hitler and his Nazis took up sparks from the torch of Nietzsche in a crusade to bring forth a new German superpower. Hitler was an Alexander who failed and was driven back by the half-barbarian Russians and Americans. Yet the outcome would’ve been little different for a man like Jünger. The victory of either side would only have meant life under the tyranny of Hitler, Stalin, or America.

Jünger uses the metaphor of a mouse to describe the Anarch’s secret preparations :

“There, safe and sound, [the mouse] hibernates for six months or longer while the leaves settle on the forest floor and the snow covers them up.

“Following the mouse’s example, I have planned ahead. The muscardin is a kinsman of the dormouse; in my childhood I already pictured the lives of such dreamers as highly comfortable. It is no coincidence that after my mother’s death I lost myself in this protective world. Lonely as I was in the attic, I became the muscardin. For years, it remained my totem animal.”

Jünger recognizes his station in the world, as a lone individual with few friends in the face of terrible predators. Birds of prey crowd the skies, ready to swoop down and tear apart little mice. The only salvation is in the reeds, in the forest, in the safe womb where one may develop and grow into something stronger.

In dim prehistory, our ancestors lived as small lemur-like creatures in the trees. Owls were their worst enemy, bearing them off in their claws to feed their chicks. Later still, the leopard hunted our simian ancestors with its terrible teeth and claws. Our shelter became the bush, the fire, the hut, and in our little fortresses we developed into higher predators that went on to subdue all other life on this earth. Again, we are faced by predators backed up by legions of slaves, and our salvation lies now in a shelter within our own minds.

Jünger addressed the question of long adaptation in another of his works, Copse 125.

“We find in the fossil-bearing strata of the earth the remains of beings with powerful armour, claws, and teeth, which suggests such alarming powers of attack and defence that it is difficult to understand how they allowed themselves to be crowded out in the struggle for life. It can only be supposed that they were specialized to excess in one direction, so that the least alteration in their existence, that is to say, in the fight for existence, sufficed to exterminate them.”

The titans who rule the world today will not do so tomorrow. They, like the monsters of the fossil record, are overspecialized and will topple as the world changes and they cannot adapt. We must prepare for this day, a day perhaps beyond our own lifetimes, where in the wake of the eventual destruction, we can rise to build a new order. Until then, we must live as mice in the attic, carefully padding our nests to survive the depths of winter.