Mishima and the Lost Position

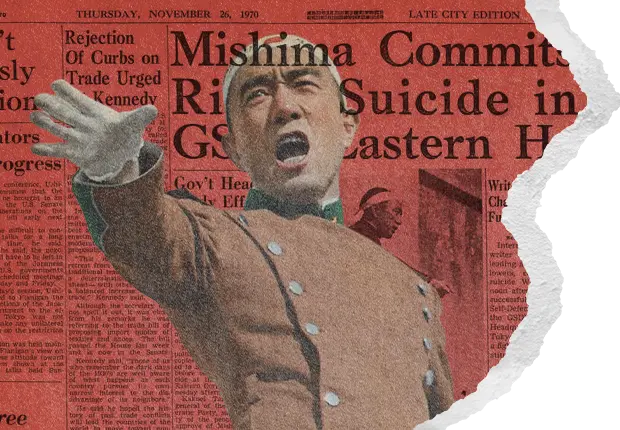

Yukio Mishima stands on a balcony and delivers a rousing speech, calling for the military to take control of the State. He declares “long live the Emperor” three times.

He disembowels himself and his comrade hacks futilely at his neck before another steps in and removes his head.

The Last Man blinks.

THE HONORABLE DEATH

A warrior cannot die an honorable death except at the hands of another warrior. When there are no worthy opponents, a true warrior knows there is only one other way. Mishima did not commit suicide because his coup attempt never materialized, nor because he knew the rising tide of the left was going to further bury the nationalist movement. In other words, his suicide was not one of despair. He died the way he did in in order to reclaim the one thing left to the warrior: an honorable death; to die on one’s own terms. Spengler said “the honorable end is the one thing that cannot be taken from a man,” but how can an honorable end be given in the West? We have no tradition of ritual suicide in our culture. One may be tempted to conclude, in this day and age, that the absence of an honorable death implies the absence of an honorable life.

The traditions of the West do contain men who chose an honorable death, who died as warriors fighting to the end to preserve their race and their way of life. And perhaps we might derive a not-insignificant amount of inspiration from these heroes. Most famously we have Leonidas, and in fiction, Boromir — perhaps inspired by Roland, who dies blowing a horn to bring Charlemagne’s army down on the attacking Saracens. These men, unfortunately, do not serve as inspiration-proper to our current predicament, because while they fought with the full knowledge of their inevitable defeat, their sacrifices ultimately resulted in civilizational salvation.

Another warrior who sacrificed himself for his people is Constantine XI Palaiologos, last Emperor of Byzantium. While Roland and Leonidas fought losing battles to help establish the cultural boundaries that allowed their civilizations to thrive, Boromir gave cover to Frodo to escape with the ring and save civilization from encroaching evil. The first two came at the beginning of civilization, while the third helped save his at the eleventh hour — an analogy, endorsed by critics but denied by the author, for fighting off fascism and saving democracy in World War I and II. Constantine, however, served no such role. He chose to die with his people, with no chance of salvation or escape.

Constantine, and indeed Mishima, come at very different times than the three heroes, and their deaths bear much greater significance to western man in the 21st century. Constantine XI lived at the the end of his civilization, and died with it, while Mishima lived after the death of imperial Japan, in the shadow of its ghost. While Constantine watched the tidal wave of history crash through his gates and wash away his people, Mishima lived in the wake of the tsunami, when everything was gone. Constantine hurled himself from the walls into the rushing tide, knowing he would drown with his people, while Mishima took his own life decades after his people had gone under. There was one crucial difference between these two men: for Constantine, there were sharks in the water. For Mishima, there was only an empty abyss.

Comparing the deaths of these two men brings our plight into focus, and perhaps makes clear our only option. Spengler says we must die at our posts, hold the lost position and preserve honor in our deaths when all else is lost. This is the position of Constantine XI, who died at his post, flinging himself from the walls of Constantinople into the fray as the Turks poured in and brought down mighty Rome, once and for all. This hopeless death was not heroic, but it was honorable. This was what Spengler had in mind, the last chance to accept your fate and face it without cowardice. At our current stage in history, indeed 50 years ago in Mishima’s time, we have lost even the lost position, and have been robbed even of an honorable death. For when there is no enemy to face down, no natural catastrophe to wash over you, what can one do?

MISHIMA THE TIGHT-ROPE WALKER

Mishima did not die in vain, nor did the tight-rope Walker in the prologue to Zarathustra. Nietzsche says humanity is a tight rope, stretched across an abyss from animal to Ubermensch. The Last Men stand on the edge of the abyss, blinking stupidly in their peace and happiness, never considering they might make the treacherous journey across the chasm. The tight rope Walker makes the move, and all stare dumbly as he goes, and dumbly as he falls and dies, and they move on. But we, like Zarathustra, love those who have in them a going-across, and we know going-across means also going-down. Mishima knew this. This is the significance of Mishima: while all others stood dumbly and blinked, Mishima went across, and by his going across he went down.

Spengler’s pessimism is a needed tonic in an age of unchecked pleasure, when your Nintendo switch and your OnlyFans subscription are supposed to inspire in you unmitigated ecstasy. But the Hour of Decision has long past. Perhaps we are tempted to follow Evola and “ride the tiger.” When you cannot fight the onslaught, instead of hurling yourself from the walls into the din of a losing battle, you hold on desperately to the tiger’s neck and wait for it to tire itself out. Evola offers a second analogy, this one from Western Mythology, of being dragged by the bull until it too wears itself out and you can finally best it.

But I can think of fewer worse ways to die than wrapping my arms around an angry tiger or being dragged around by a charging bull.

No, we cannot hold the lost position or ride the tiger. But there is another way. Mishima does not tell us that all hope is lost, or that we need to follow his example, far from it. Like the tight-rope Walker, Mishima is showing us the way across. The time was not right for him, but he had to fall into the abyss to inspire bravery in us who confront the terrible void in the soul of man today. He made a spectacle of his death to tell those who came after him that the way must be taken despite the surety of failure. For one day, the time will be right, and a man will need to come forward and seize it.

History is pregnant with the Man of the Future. I can see the undulations across its belly as the developing fetus moves in its womb. The hour may be late, but these things cannot be rushed. In a time like ours, there is only one thing for men like us to do. We stand guard at the mouth of the cave, and when the water breaks, and the New Man is borne in the rush of fluid, and he suckles at the breast amidst the after-birth, our duty is to hold at bay the wild beasts who come sniffing around the cave at the scent of blood.