Mr Roberts

If you have ever served in the military, then you have inevitably been asked at some point to comment on the accuracy of various war films, and you surely have your own staunch opinions on the subject. Every branch has their own favorites, and the sea services are no exception. Submariners will pontificate at length about everything from “Destination Tokyo” to “The Hunt for Red October.” Any naval aviator will be happy to tell you all about how Tom Cruise’s Maverick is “literally me.” Any former SEAL you meet will probably have his own podcast, book deal, and movie script to plug. Even the coasties can cling to “The Guardian.”

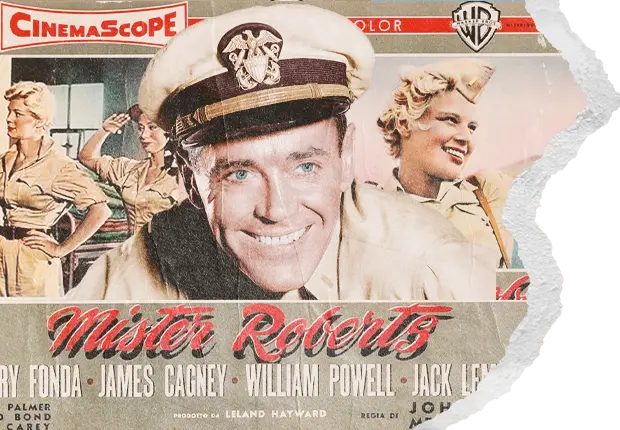

As for those of us who served in the surface navy, while 2012’s “Battleship” was a lot of fun, one must venture all the way back to the 1950s to find the truest representations of our community. “The Caine Mutiny” (1954) is a rightly well-known and highly praised classic with timeless lessons of leadership and lack thereof. But it was a less talked about but equally excellent movie from the following called “Mister Roberts” that gave the most comprehensively realistic view of the community and continues to shed light on issues facing the service today.

Many World War II movies were made during the course of the war and its aftermath. Many of them told tales of important battles and martial glory. Mister Roberts was a different type of film. It was based on a 1946 novel by Thomas Heggen (a navy veteran who was taken aback by the book’s success and died of an overdose in 1949 while struggling to produce a sequel) which begat a 1948 Broadway play. The film’s original director was the legendary John Ford, whose prior experience with the naval world included capturing live footage of the Battle of Midway. However, Ford left the project during filming due to both medical reasons and conflicts with the cast, and was replaced by Mervyn LeRoy and Joshua Logan.

The story centers on a small supply ship aptly named the USS Reluctant as it thanklessly toils through the South Pacific, many miles behind the frontline action, in the waning days of WWII. Henry Fonda, who had actually served with the navy in the Pacific during the war, stars as the titular Lieutenant Doug Roberts. Serving as the ship’s XO and cargo officer, Roberts is well respected by the crew, but longs for a transfer to a frontline combat ship. James Cagney plays Captain Morton, a petty tyrant cast in the same mold as “The Caine Mutiny’s” Captain Queeg or “Mutiny on the Bounty’s” (unfairly maligned by history) Captain Bligh. In a role that earned an Academy award for Best Supporting Actor, Jack Lemmon portrayed Ensign Frank Pulver, an unmotivated junior officer so skilled in the art of “skating” that the Captain doesn’t even know his name. William Powell, in his last major film role, rounds out the principal cast as the ship’s doctor, and the story’s moral compass.

We join the Reluctant’s crew in the midst of their South Pacific supply runs. There is a world war going on out there somewhere, but one wouldn’t necessarily know it. They are operating in an endless cycle of working hard on tedious tasks and being reprimanded for petty infractions by egomaniac Captain while traversing an endless blue water expanse. LT Roberts does what he can to ameliorate the crew’s experience by shielding them from the worst of the Captain’s wrath, and pushing back against his excesses whenever feasible. Meanwhile, he periodically submits formal requests to transfer to a cruiser or destroyer closer to the action, which captain Morton summarily rejects.

While Roberts wages his sisyphean struggle, Pulver has surrendered to ennui, spending his days lying idle in his rack, and occasionally thinking of ideas for pranks that he lacks the nerve to actually play on the captain. The only time we see him perk up is when he plays an eager tour guide to a group of visiting nurses. (If this scene were to be cut, the movie would pass the Master and Commander reverse-Bechdel Test of having no women with speaking roles). Pulver is finally spurred into action when Roberts calls him out for not acting on his prank ideas, but his planned trick of setting off a firecracker underneath the Captain’s rack only results in an accidental explosion of the ship’s laundry system.

The crew continues to, in Roberts’ words, “Sail from tedium to apathy with an occasional side trip to monotony.” With no in-port liberty in a year, the crew is near its breaking point. Roberts takes matters into his own hands by going over Captain Morton’s head to accept an invitation of a port visit from a more senior captain in charge of the port facilities on a tropical South Pacific island. However, when the Reluctant arrives at the port, Morton makes a last minute decision to cancel the crew’s liberty, the type of bait and switch that could permanently break their spirit. Determined to rectify the injustice, Roberts confronts Morton in his cabin and asks him point blank what he would have to do to get the crew a night of liberty. After a heated exchange, Morton agrees to grant the liberty in exchange for Roberts agreeing to stop submitting transfer requests and no longer push back against his orders.

Like sailors have always done for all of time immemorial, the crew raises hell onshore and instigates all manner of what the modern navy classifies as “alcohol related incidents” and generally have the time of their lives, while Roberts remains onboard as a duty officer. After the brief reprieve the crew gets back to business and back to the old routine. There is a noticeable change in Roberts, and the crew is confused and concerned as to why he seems mentally checked out and isn’t having their back against the Captain anymore. Meanwhile, the Captain’s tyranny becomes even more oppressive and petty than ever. (Skip the next few paragraphs if you care about spoilers, but come on, you’ve had nearly seventy years to see it.)

When things finally come to a head, Roberts takes out his frustrations on the physical embodiment of Captain Morton’s toxic leadership, a potted palm tree on the ship’s bridge that he had been given as a prize, by throwing it overboard. Soon thereafter, Morton summons Roberts to his cabin for a heated confrontation that is inadvertently picked up by the ship’s PA system. Through this accident, the crew finally learns of the deal that Roberst had made to get them liberty, and their trust in him is restored.

At the story’s climax, Roberts unexpectedly learns that his long awaited transfer has been approved and he will be joining the crew of a destroyer in the thick of the action. In a private moment, Doc reveals to Roberts that the crew had sent out their own transfer request on his behalf, and had forged the Captain’s signature on the document after holding a contest to determine who could write the best version of it. Before Roberts leaves, the crew presents him with a handmade medal as a token of their appreciation, and he tells them he will treasure more than a Medal of Honor.

In a moving final scene after Roberts’ departure, the crew assembles for a mail call and receives a letter from Roberts containing a wealth of heartfelt advice and appreciation. Meanwhile, Pulver receives another letter from a college buddy serving on the same destroyer, in which he learns that Roberts has been killed in a kamikaze attack. Realizing the shoes that he must now fill, Pulver marches up to the bridge, throws the Captain’s replacement prize palm tree overboard, and storms into the Captain’s cabin to confront him about canceling the crew’s movie night.

While Mister Roberts may be based on the specific experiences of a World War II sailor, it speaks to universal experiences that continue to ring true to sailors today. At a time when the U.S. Navy is struggling to find enough recruits (according to the U.S. Naval Institute, the Navy fell short of its recruiting goals for Fiscal Year 2023 by over 7,000 sailors), and has been plagued by stories of scandals and mishaps, the issues illustrated by Mister Roberts may shed some light on why.

One of the principal themes of Mister Roberts is the idea of encompassing, soul crushing boredom. For the crew of the Reluctant, the world war raging miles away from them may as well have been occuring on a different planet. They exist in a self-contained bubble, performing the same monotonous tasks on an endless loop for months or years on end. A big part of why this film strikes such a chord with me is just how closely this resembles my own experience of the Global War on Terrorism. As a navy sailor, I spent plenty of time in the general vicinity of ongoing conflicts in Iraq, and Afghanistan, among other places. But no matter how adjacent we were to conflict, you would never know one was going on unless you watched the AFN news. Our days were the same endless cycles, standing long watches of staring at aquatic expanses for hours at a time, performing tedious maintenance tasks, doing random busy work for what often seemed like just the sake of doing something, and grabbing much needed sleep whenever you could. We could have been in any body of water anywhere in the world and it wouldn’t have made a lick of difference.

Another issue that is well illustrated in the film is the type of op tempo that is demanded of the sailors. As the navy becomes smaller, but America’s overseas involvement remains steady, ships’ deployments have become both longer and more frequent. No one can deny that this places a great strain on the crews, and is certainly a negative selling point in recruiting. The most important mitigating factor that can restore morale in this situation is port visits. As a Pacific Fleet sailor, I was fortunate enough to experience liberty ports throughout Asia, Australia, and the Pacific islands, and these visits provided my best memories of the service as well as much needed break from the grind. The sailors in Mister Roberts are pushed to their breaking point by a lack of liberty ports, and when they finally get to enjoy a long overdue night on the town, the force of military discipline strikes back at them over their drunken conduct. I once went over 90 days at sea without pulling into port, which at the time felt pretty close to a crew’s mental limits. However, in the post-Covid world, ships have routinely exceeded these kinds of stretches. In 2020, the destroyer USS Stout set a new record by spending 215 days continuously at sea. While Covid restrictions may account for the most outlying numbers like that, it is undeniable that deployments have become, on average, longer, more frequent, and with less opportunities for liberty. And those opportunities for liberty that do come along will be done so under the weight of risk-averse micromanaging disciplinary restrictions that threaten to sap the fun out of them.

Finally, the film’s depiction of Captain Morton is a great example of the type of toxic leadership style that the surface navy community is notorious for. One need only type “Navy Captain relieved” into the search engine of your choice to bring up pages upon pages of stories of similarly dysfunctional and disastrous leadership styles. (Look up “Horrible Holly” Graf for a particularly entertaining example). There are many factors that go into this type of toxic culture, and many theories to take a stab at explaining it. One is that surface warfare is the navy’s “default” community, and many who end up there are not exactly happy to be there. Another is that the system of promotion and ranking against one’s peers selects for sociopathic behavior, and the best officers end up getting out. Whatever the case, when the leadership issues combine with a demanding op tempo and the boredom inherent to the job, the navy’s recruitment problems should be no wonder at all.

It is a commonly lazy take among the lowest brow type of clickbait conservatives to blame the modern military’s issues on “wokeness.” While the current administration certainly is pushing DEI initiatives that will undoubtedly have a negative impact on military readiness, it is simply the cherry on top of the deeper existing issues. The other service branches no doubt have similar stories to tell. After all, it wasn’t “wokeness” that made us spend twenty fruitless years trying to bring democracy to Afghanistan.

Looking beyond issues of naval warfare, what lessons can Mister Roberts tell us about society as a whole? Whatever euphemism you want to use for today’s powers-that-be, “the regime,” “the cathedral,” “the longhouse,” etc, the characters of this story were living it on an oppressively small scale. Every day, their natural vitality was drained away by a combination of tedium and toxic leadership. How did they deal with it? Ensign Pulver spent most of the movie black pilling and giving in to despair. His response was to check out, give u hope, and retreat inwards. Lieutenant Roberts, meanwhile, shows us another way. He resists. Not in a reckless manner by “fed posting” and inciting mutiny, but intelligently and diligently. He protects his friends from petty tyranny the best he can, and keeps their hope alive that things can be better. As he tells the crew in his final letter, “The unseen enemy of this war is the boredom that eventually becomes a faith and, therefore, a terrible sort of suicide. l know now that the ones who refuse to surrender to it are the strongest of all.”