Schultz and the White Stone

Mr. Schultz labors down the stairs holding his dirty laundry. He kicks the bottom step three times, like a lazy mule trying to drive away a pestering insect. Or Dorothy conjuring her homeward flight. Short, fat, awkwardly proportioned, obsessive little Schultz is out of breath by the time he crosses the tiny lobby of the small decaying hotel where I work as night manager.

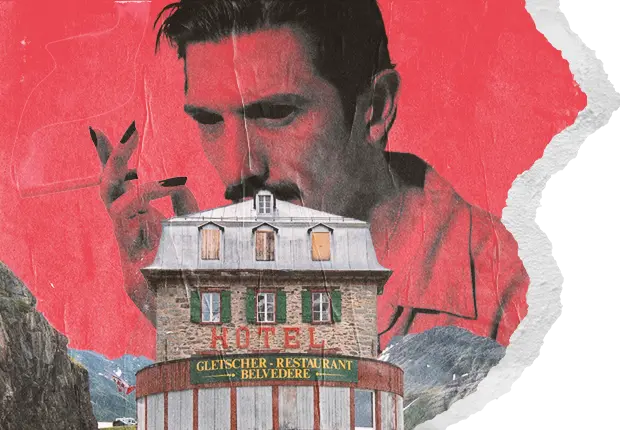

I can see he’s going to want to talk. His porcine cheeks flare with dramatic excitement as he puts down his basket and approaches the counter. Mr. Schultz has the dignity of a tall thin man inside the body of a short fat one. He seems to have stepped out from a faded daguerreotype of a German shopkeeper, posed in front of a colorless curtain in some small artist’s shop. None of this is out of place here in the Northern Midwest. Schultz could almost be a type, if he didn’t diverge so much from himself. Old Schultz the failure, the shut-in. Schultz the nocturnal resident of the fifth floor in the dingy hotel in this more than chastised midsized midwestern city. I wonder what he would have been 50 or 100 years ago. I know what the city used to be…

“Going to do your laundry tonight, Mr. Schultz?”

“I’ve got to do my laundry. Going to do my laundry tonight.”

His obsessive compulsive speech patterns can be frustrating, or they can be soothing in their predictable repetitions. I choose to find them comforting – when I am able. When I have that poise that results from self-satisfaction. The lazy self-satisfaction of an ambitionless man fulfilling his lazy ambitions in a job that barely requires the illusion of labor.

“That’s one thing I miss about the old hotel. The elevator.”

“They had an elevator where you used to live?”

“Because there they had an elevator. You could take the elevator. You didn’t have to walk. Didn’t have to walk up and down the stairs because they had an elevator. At the hotel.”

He takes a deep breath. He’s already wearing himself out with all this friendly conversation.

“At the old welfare hotel where I used to live,” he finishes, satisfied that everything has been said sufficiently, clearly and with the right amount of emphasis.

He’s talking about The White Stone, the old welfare hotel, long ago turned into a luxury apartment building, though the area remains… grungy, let’s say. Rundown. And the downtown onto which it looks, as if from the outermost edge, is no longer packed, thriving, bustling. It’s a shell. Blown out, half-empty – like half of the formerly thriving cities in this shell of a country…

But still, every town has at least a few rich residents – and the upper middle class, tied to the area, making their living in law, city politics, development… They need condos, restaurants, bars. And you have to put them somewhere, even if that means somewhere in the ruins. And look, there are greater and lesser ruins. Nicer ruins, cordoned off from the more terrifying rubbish piles. A few blocks here, a few there… with ominous, half-empty parking garages filling in the gaps.

So too here. Hence the decision to cram million dollar condos into the former welfare hotel, even if it overlooks a typically empty “main street,” where, at any given time, you can still easily find panhandlers, junkies, muggers on almost every corner. What a view! What monstrous proximity.

Mr. Schultz tells me about his last years in the hotel. How they stopped fixing the place. They’d never done much, of course, but then… gentrification was in the air! It came in the windows on a rumor. It blew in with the pollen that Spring. A sale was in the offing, and so the tenants were slowly forced out. Slowly – this isn’t Manhattan, or even Chicago. Here it takes a little time for a neighborhood to turn over. And even when it does, it never turns all the way over. Like a reticent whore, this town flashes a little thigh and then insists we turn out the light… But I guess Division Avenue changed enough to make it worth some developer’s while to force out the renters, gut the place, and sell it out to the city’s rising ephebes. The fresh out of law school yuppies. The trust fund children who spend a few months here every year to justify their payroll taxes and incomes as part of their parents’ businesses. They drove the muggers and enough of the panhandlers back a few blocks across the river and thereby justified the sale price of these two and three bedroom monstrosities.

Now, right around the corner is an ancient diner. One of the last greasy spoons in the neighborhood. Somehow we get off the subject of The White Stone itself, and Shultz begins to rhapsodize about the neighborhood before its recent makeover. Back in to the 80s and 90s, when all those avenues had been abandoned, and the movies houses finally closed down. When instead of crowds streaming out after the late show, you had a few tottering drunks stumbling out of the remaining bars, too poor to be robbed, and too far gone to care if they got rolled anyway. When the hosiery counters closed and the variety stores soon followed. When Shultz and a few others were left behind in the devastation. Left behind with a few remnants of the early postwar years. Places owned by men too stubborn, too broken, or too deep in debt to move their business elsewhere. Places like Peterson’s Diner.

By then, Shultz tells me it had become the late-night hangout for hookers and their pimps.

“Oh, oh… they used to sit there all night. You just had to ignore them if you could. If you wanted to get a hamburger. Get a hamburger. Or if you wanted to get a soda. When you wanted to get a soda.”

Mr. Schultz has been hiding his repetitions fairly well tonight, but the thought of all that polluted flesh hanging off the stools at the counter of Peterson’s is too much for him. He starts doubling and tripling up.

“I used to go in, though. And have a coffee. Go in and have coffee. It really wasn’t that bad. It wasn’t bad. In the winter they’d meet their Johns right outside, so… no one bothered you if you wanted to sit and have a coffee.”

Schultz used to talk to the whores, but swears he never slept with them – he says this, and I believe him. If anyone could have merely observed, holding in his desire, savaging his impulses, grinding them to dust… well, that someone would be Schultz. I’d tease him, ask him if he was ever tempted – that is, if it was anyone else, I’d ask him… But Schultz…

He fidgets and squirms, the pink in his cheeks showing again. His recently shaved, fleshy cheeks flash red, while his nervous fingers start pulling and tearing at each other, mounting to a frenzy… Eventually he can’t hold still any longer and he shakes himself closer to the desk.

“But now they don’t let them in. They started locking the door at night. They lock the door at night…”

“They only do takeout? At a diner?”

“They don’t let you eat in at night. They’re trying to clean it up. Clean it up in that area. In that area, they’re trying to get it cleaned up.”

He’s stuck on triples. I’m getting worried.

But it’s a sad story, I have to admit. In the city’s ineffectual attempts to clean the area up, they’ve made it so the pimps have nowhere to sit at night. The whores have to shiver under the highway overpass. They can’t sit down at the counter, smoke a cigarette and rest their feet in between Johns. More progress. More sanitized appearances, covering ever more violent realities.

“Well… I just came in for quarters. I just need some quarters.”

Mr. Schultz is afraid of the coin machine in the guest laundry, so I break him off some “clean” coins from a new roll in the drawer and let him go on his way. He clicks his heels and disappears.

**

Later that week I’m walking across pitiful, filthy 3rd street, past the strip club and bodega, over near the grimy edge of the river, and I see the diner. Peterson’s Diner, glowing in the blue night, like some 1980s travesty of Nighthawks. The red molded plastic seats beckon to me and I go in and have a coffee. It’s 9 O’clock and the place is empty. Schultz is right: not a pimp in sight. Just a few Mexicans in work clothes, a lost-looking middle aged woman, and a limo driver reading the paper. There’s nothing to see. When you clean a place like this up, you kill it, too. The spectacle of wretchedness is like an anchor for the human. And it’s yet another measure of the increasingly inhuman world that’s grown like a parasite slowly swallowing its host, slowly taking the body over, that this cleaned out place, this dusted off, disinfected restaurant has ceased to be a draw. Even the waitresses look bored.

But maybe there’s still time… Bring back the filth! Revive the degradation! You have to goad your fellow sufferers into communion. Give them something to celebrate. We excel pigs in the trough if at all only by our ability to suck down rancid entertainment – while we chew. I want something with my sandwich. I want the whores marching by. I want the occasional stabbing in the bathroom, sirens outside, yellow tape… I want a reminder of life, if not life itself. Give us something that tunnels toward our hearts… this subterranean burrowing… this worm in the pig…

Instead of which… in shuffles a UPS driver and his noisy kid. Time for me to go.

But, turning the corner, I decide to take a look at the old welfare hotel. The “grande dame of welfare hotels,” as Mr. Shultz likes to tell me in barrages of three. I’m picturing how it used to be, when there was still some lingering sense of the old world in this country of ours, some hint of what we thought we were superseding in these cities. Before the fast food chains and the pharmacy chains and the yuppie glass cube condo buildings came in. Before the race riots and the long sure decline of the 1970s. When families still lived downtown, and taking the bus after dark was a normal activity. Before the wretched of the earth pitched their tents under the bus shelters.

I can picture it as Schultz must have first seen it: a big lobby, slowly decaying. The upholstered armchairs fraying delicately beneath a cloud of cigarette smoke and slowly widening American asses. Men getting their shoes shined, buying newspapers and cigars at the concession stand. Chandeliers, carpet, ferns, standing ashtrays and umbrella stands. But from there it emptied out, the guests dried up. So they converted it to apartments – but that didn’t work either, so eventually it went section eight. They cleared out the lobby, put a table or two in for packages, got rid of the carpet (too difficult to clean). And as the neighborhood declined, the hotel became a relic. Fewer European accents, more down on their luck workmen, blacks, drinkers and pimps – and then single mothers and men who wouldn’t know luck if it shit on their banana. Men like Schultz.

Because the gods hadn’t been very kind to Mr. Schultz. They started with OCD, gave him a stutter on top of that, made him prematurely bald, nervous, fumbling, unable to hold a job – unable, often enough, even to leave his apartment. If that uncle of his hadn’t kicked off, poor Mr. Schultz would have wound up across the city, in a part of town no Schultz (or Wertmüller, or Smith or Kowalczyk) had gone in many decades, in a tower block run, in effect, by one of the various gangs who’ve long held the unofficial mayoralty over there… But the gods took a break from their aggression and knocked off his relative instead, which gave Schultz enough of an income to move permanently downtown into our hotel. An actual hotel, however decrepit – with paying guests, and apartments on the top three floors. And that’s where he’s been living since 1992.

But through the 80s… well, he was on the 10th floor of the “grande dame of welfare hotels.” And when the elevator broke – which happened with increasing regularity as the years wore on – Mr. Shultz found himself sweating and groaning all the way to the top, where he would stay for days, against the possibility of having to climb it again. Imagine having to hit your heals against every landing for ten flights? The poor bastard.

And now, from the outside, all you can think is who in this city can even afford such a swanky place? It’s been restored to its former glory, in one sense – from the outside it looks immaculate. Cornices repaired, new windows, new frames, the canopy above the entrance restored, burnished, shining in the sun…

Yes, from the outside it looks like the old days have returned – though I’d bet money that they did a “gut rehab” inside. Probably now there are open kitchens and exposed brick and every other yuppie contrivance. Yes, from the outside, it sure looks like a time gone by. But of course nothing has returned. It’s not a hotel. There’s no lobby. The simple human niceties it used to house – sitting next to the potted ferns and reading your paper while you wait for your mail – gone, irrevocably. There’s a hotel down the street, but of course it’s a chain, the lobby is basically a plastic husk, indistinguishable from the one they used in Fort Lauderdale, Phoenix, San Diego…

I picture Schultz walking nervously out of this door and down this street in the 1980s, on the lookout for muggers, bad omens, his own reflection in the windowpanes. I pull the door and find it locked, as expected. It’s not surprising. But I had to try. Maybe catch a glimpse of some remnant of the old lobby – the tall ceilings, the crown molding. No luck. There’s no getting in here.

So I walk down to Father Timorem Park, by the dingy black river that runs through our downtown, where the Historical Society occupies one of the few remaining historical buildings in the neighborhood. Amid the wreck of a flattened corner, a no longer functioning drawbridge, and a decaying neoclassical pavilion, there’s a kind of seasonal homeless encampment. Impossible to believe, incredible as it is… the city does get visitors every summer – mostly to see the local pro sports teams or drink themselves stupid in one of the many bars surrounding the stadium. And so for a few warm months, the park is cleared, cleaned, and remains mostly off limits for the junkies, bums, and prostitutes. But in March…

I cross the park, picking my way through the litter, discarded clothing, a few old needles cradled in the long uncut half-frozen dead grass. Making my way to the river’s edge.

I’m emerging from a patch of nauseating brightness, under an uncovered street light – one of the few still functioning over here – when a filthy man laboring heavily under four or five layers of ripped coats and grimy sweatshirts opens the flap to a tent pitched at the edge of the now unused “River Walk,” and comes outside to fight with a company of pigeons circling and landing on his cracked tent pole. After a few warm days, some of the birds came back. And the more intrepid squirrels. A few warm days, then another frost. I guess the pigeons took refuge here in the pavilion. Now it’s a fight between the junkies and the pigeons for control of the other’s territory…

In my experience it’s unwise to fight with birds. Especially city birds. They’ll come out of nowhere, without breaking the silence, and sink their diseased talons into your skull. They’ll peck through the skin in a matter of seconds, before you even hear the wings flapping.

But the bum hits out at the birds with a broom handle, collapsing one side of his tent in the process. He cries out in frustration, just as the last bird squawks away into the upper air. A pyrrhic victory. The wind blows the flaps until it seems to uproot half of his stakes… But he persists.

In the relative silence of only bus engines, the echo of the interstate, and the occasional car horn, the bum rebuilds his hovel. But the sounds alone! They’re almost worse than the junkie. To inflict them on a once quiet park by the river! Thus Time in its guises crept in here, soiling the place as much as the junkies have done. The black streaks of exhaust and the computer-generated voice blaring out the number of the route every five minutes as the buses lurch up to the shelter on the corner of 5th street… One indignity balanced out by the others. Round robin. If only every beginning could see its end, the world would remain in total silence, stillness and death. But then, all the indignities of action lead it there eventually, too. No wonder men make of the birds something holy, in the detachment of flight, of distance… escape.

**

Whenever Shultz emerges from the laundry room he wants his paper. I have a growing affection for Schultz, sitting quietly with his paper in the lobby at 3 or 4 a.m., tittering to himself over the news. Because you’re right, Schultz, it is funny. It’s hilarious. The doings of the yahoo. The toing and froing of the over-clever ape. Lucking into civilization and then blundering it away…

He gets the local paper first, as if to warm up his jaw for the laughter of the national news. The day’s disgrace writ large. He starts with the local corruption, the local, smaller catastrophes, and then he moves on to the continental disgrace. Giggling, shrugging, scratching his head, throwing up his hands – Schultz works like a mime at the edge of the lobby, tucked in between the plastic fern and the leaded glass windows. He signals contempt, confusion, shock, horror, speechlessness…

The process is always the same: he buys his paper, chooses his chair, flips the cushion (wisely, it seems to me – in order to be free of the last man’s contamination!) He sits down with a moan. How could it be avoided? Schultz moans like other men breathe. Which, again, convinces me of his wisdom.

Having warmed up with the city news, he’s ready to go national. Today the big story was the arrest of a local cop who’s been selling guns to the city’s gangs. And clean license plates for the stolen cars. Giving them heads up on raids, accessing the addresses of their enemies. Tips for easy escape on high speed chases. This guy was really a great help to the local economy. That’s one way to look at it. Shultz shakes his head and grunts as he comes to the desk and asks me if I’d read the story. We lament the state of things a while, before Schultz punctuates the conversation with something like my own thoughts.

“But anyway… what’s really new in this?”

“Not much I guess.”

“There’s nothing new in this. It’s not new.”

We’re holding at double repetitions. So it’s a good day so far.

“Corruption, greed, lack of honor. Just more corruption. No honor.”

“Just the inevitable end of American values… Or their final realization”

Schultz reflects on this thoughtfully, before agreeing.

“It is. It’s sad. Sad, but that’s what it is.”

“Get it at any cost.”

“They don’t care what it costs. It doesn’t’ matter what it costs them.”

“Or us.”

Schultz sighs, itches his beard.

“You want a New York Times now, Mr. Schultz?”

“I think I’ll take a New York times now.”

And he goes back to his seat by the window. He likes to open it a little bit, to let the fresh air in. He complains how stuffy the lobby gets. I agree. It’s great when Schultz comes down – I have an excuse to open a few windows. They’re on the ground floor, of course – but they’re too narrow for the bums to fit through. Even the most far-gone junkies can’t wiggle in. You can’t leave the front door open for long – but the windows are ok. There’s some kind of lesson in this. Apertures can’t have the shape and scale of a human body, unless you want to invite their fetid horror into your building, too. Something like that. It’s imprecise. I need to flesh it out more… it’s not yet a good epigram… but you get the idea.

The yahoo-shaped-hole.

Yes, that’s it! I really do have a way with words! Possibly I will become our day’s Martial, if not Juvenal… In the meantime, I’ll sell Schultz a USA Today.

**

Schultz doesn’t cook for himself. I don’t think he can. But in any case, he had the stove taken out of his room – afraid of the gas. So he simply eats in our restaurant, usually twice a day. I think he keeps crackers up there. And a few times a week he calls down and asks me to bring up a glass or two of milk. He’s a poor man’s Howard Hughes. The aviator with shorter toe nails.

Really, he hardly leaves the hotel at all anymore. He comes down at night to read and sit in the silence of the lobby. He’s told me that my presence doesn’t bother him, since I’m quiet and am usually reading myself. On the other hand, he avoids the alternate night man – who gets bored, tries engaging Schultz in conversation and won’t let him read in peace. A man who views solitude as a curse. A watcher of television on his tiny screen…

Yes, the old man avoids Lang, who he sees as desperate and feeble. Lang the carnival attendee, the audience member… With his bent neck, his chicken-neck, and bulbous if still somehow undersized midsection… Lang the desperate, always-bored – Lang the standard poodle: whiny and forlorn, silently begging for attention.

This dislike of Lang provides me with another reason to praise old Schultz. Usually I tense up when someone appears at 3 am. I took the job to avoid people, to sit in peace and quiet. And then someone shows up and starts talking. The sound of a human voice is a destroyer of worlds. I see the mouths open, and there’s a terrible moment before the noise emerges… The pretty girls feel justified, and begin speaking immediately, never conceiving that anyone might greet their offer of conversation with anything besides simple gratitude. The ugly women are better – they are by nature more apologetic for their presence, and there’s often a blissful pause during which I’m able to believe they’ll think better of whatever inane sentence is forming at the back of their embarrassed brains… But even the ugly speak, eventually.

They all think I want conversation. Because they imagine their own feelings in a similar situation. How they would feel if they were forced to work a long overnight shift in silence and solitude. How they would feel in the silent, empty lobby. But what they fail to grasp is that I chose to work this job, this shift. The last thing I want is aimless small talk. They assume that I find comforting what they find comforting. They believe in equality before god – or in the brotherhood of man and the citizen! Which is much the same. They think I read only to pass the time – until something better comes along! They believe there is something better…

Not Schultz. We speak for a few minutes, then sit in silence for an hour. Another five minute conversation, another hour of silence. Then Schultz nods and either goes upstairs, or, if it’s laundry day, asks me to carry his bin for him, back to the 5th floor. He tips well, does Schultz. Even though I always tell him it isn’t necessary. Ten bucks a trip. His back is no good. He can barely feed the clothes into the washer, let alone carry the whole basket.

Yes, tonight Schultz is doing his laundry and reading the New York Times. He guffaws, titters, removes whole sections in anger. He’s working his way through it before moving on to the Wall Street Journal, which, as he says, is “at least partly serious.”

“It’s at least partially serious. It’s almost a serious newspaper. Not like the Times. The Times is totally unserious. It takes up its position – takes it up and pursues it, dishonestly. Pursues it wherever the logic leads it. Not the facts.”

“That’s true,” I say – and I mean it, too. “The Times is immune to certain facts.”

“Immune to them or afraid of them.”

I nod my approval.

“It’s afraid of them, won’t admit them. It excludes the facts and continues the interpretation without them. It just leaves them out!”

Schultz is getting more worked up than usual at this stage of the night. I begin to wonder which stories he read from the day’s Times. But before I can ask, a late check-in rings the front bell, and, after scrutinizing him on the monitor, seeing a suitcase and intact clothing, I let him in. But Schultz sees nothing of this, hears nothing, just continues his monologue.

And I try to signal that I’m happy to talk, but I will have to deal with the customer first. The customer, who, sneaking up on Schultz without meaning to, winds up by frightening him, as he swings his suitcase around and pushes up to the front desk, just next to my friend. Towering over him by at least a foot, he’s sober, well-groomed, obviously tired from travel, and, seeing that I’m talking to what he must perceive as another customer, content to wait. He tries. But Schultz, shaken only briefly by this sudden, unexpected presence, continues his monologue on the decline of the Gray Lady. He goes on and on without any indication that he might soon come to a stopping point. He barely breathes in between the avalanche of insults and accusations, during which it emerges that in fact The Wall Street Journal is on the same slope as the Times. Yes, Schultz seems about to embark upon a parallel tangent, condemning the “nominally conservative financial rag” alongside the “formerly liberal paper of record.”

“They take their orders from the same class, the same voices barking in the same well-trained ears… They get the same training, without even knowing it! And they’re just a foot behind on the slide – though possibly there is more margarine underneath them! More margarine, and so the speed increases. They’re catching up!”

And now, despite being treated to this rather remarkable insight, the actual guest begins to grow impatient, fidgets, looks around, trying to find some sign on Schultz’s face that he grasps the situation. But Schultz, stuttering, raging, almost fuming, like an engine with insufficient oil, rages on, getting hotter, redder in the face… I think he knows by now what’s wanted of him, but he remains committed to finishing his disquisition… like an autopilot he can’t override…

And then finally, inevitably, the other man speaks.

“Excuse me… I… I just want…”

“Mr. Schultz, I just need to check him in. Would you mind… just a minute.”

Schultz tries to comply, steps aside. And the guest hands me his ID and credit cards. I begin the check-in process. But Schultz is still fidgeting, growing redder, trying desperately to hold back the impulse to cut in, the need, really, to finish the tangent he was on, which was supposed to culminate in his retrieval of the Wall Street Journal, and his return to the chair by the fern, the window, the table where he’s left his reading glasses…

And in the end, he can’t restrain himself.

“Yes, but I just need a Wall Street Journal. Just a Wall Street Journal, please…”

“I know, Mr. Schultz. Give me a minute and I’ll help you.”

“Just a Wall Street Journal, please…”

But now the guest is getting frustrated. And it’s not his fault, really. He’s probably had a long, exhausting trip from somewhere – some godforsaken strip mall passing for a town. Some edge of the trade zone that used to be a country. Eventually he can control himself no better than his antagonist.

“What’s this guy’s problem?” he demands, though it’s clear that no response of mine could mollify him.

“I’m sorry, sir. Just let me sell him a paper and we’ll get you checked in.”

I’ve perfected the pretense of patience. The mask of concern.

“But I’ve already given you my credit card. Let him wait.”

Apparently this guy is going to be a stickler for the normal order of things, a believer in the standard ways of the world. Which is fine, and understandable enough. But it’s not pragmatic. And he must not be very observant. Because if he really wanted to expedite the process, he’d assess the man he’s dealing with, see that something is a little off, and act accordingly. He seems to prefer the proper and expected form of the thing, without regard for the actual substance.

“Mr. Schultz, can you just give me a minute?”

“Just a Wall Street Journal. A Wall Street Journal.”

“What’s your problem, pal? Can’t you see he’s taking care of me?”

“Sorry, sir, maybe if you just give me another minute I could – “

“I don’t see why I should have to wait any more!”

“Just a Wall Street Journal, just a…”

The guest swings half-violently toward Schultz, who, on his best day, is the picture of timidity, and so in this tense moment becomes as frightened as the proverbial mouse. He turns away, pivots almost elegantly in his terror and flees behind the plastic potted fern, like a miniature Falstaff obscured from battle by his rock.

“I don’t believe this,” mutters the traveler.

“Let’s just finish getting you checked in…”

But even now, from behind the fern comes again the feeble request: “Just a Wall Street Journal…”

“I wasn’t going to hit him, I just… was just pointing…”

“Just a Wall Street Journal.” It’s almost an echo… But it’s audible…

Shaking his head, shocked and almost apologetic, the traveler signs the registration card, takes his keys, and wanders off, stupefied by the exchange, and also more than a little disgusted. But while I understand his position well enough and can even sympathize with it more or less – there is justice in it, no doubt, even if of a limited nature – still, I feel myself siding more with the admittedly and obviously outlandish demands of stubby Mr. Schultz, my tiny whirlwind of spite and recrimination… And now, like some displaced Old Testament prophet, condemned to a lifetime of shame and degradation in the American Midwest, Schultz now, when his bodily safety no longer seems threatened, unleashes a torrent of minor violence and destruction onto the already disintegrating lobby…

Hurling – or rather struggling mightily to overturn – the cheap, if enormous, ceramic pot, he manages to get the fern as it were uprooted (though of course, being fake, it has no roots). Then, taking the fronds in hand, he proceeds to beat the synthetic mulch against the floor and edge of the front desk until it comes free of the “plant” and turns into just so much brown styrofoam dust… after which he rips each shoot of the plant apart, until the mess on the floor below him resembles chewed and abandoned stalks of celery from an undercooked winter stew…

“Mr. Schultz, please!” I try to discourage him as I come around from behind the desk. Though my discouragement winds up sounding more like comfort: “It’s ok now – he’s gone!”

But Schultz’s rage can’t be contained. He stomps on the strings of green plastic, kicks them away and takes aim at another fern, across the room. I rush over there, doing my best to stop the pandemonium without laying hands on him. I show my palms, shake my head, speak in conciliatory tones.

“Mr. Schultz, please stop!”

He moves as if he’s a football player trying to juke his way to the endzone.

“Please, he’s gone, and this will take all night to clean up!”

Schultz’s footwork is surprising. He manages to throw me, as if he set an invisible pick, and rolled on just when I leaned in to lay hands on him. He’s past me now and ready to destroy another pot.

“Mr. Schultz, they’ll kick you out!”

This is what finally stops his rampage. Is probably the only thing that has any impact on him – the absolute terror of ending up somewhere worse than the old White Stone. Because he knows that now there are only very expensive and very dangerous alternatives to the miracle of this hotel, this last affordable holdout among the old residential hotels in the fraying downtown…

He looks around, as if suddenly cognizant of everything he’s done. Coming out of a haze, like a drunk waking up after a long blackout and wondering why it smells like urine in his bed… Forlorn, contrite, horrified, even, at the mayhem he’s unleashed – he, who, for long, buttoned up years didn’t even allow himself so much as a string of profanity, let alone physical violence…

And then it hits him fully, and he shakes his head, gesticulating around him as if standing on a smoking battlefield.

“It’s ok, Mr. Schultz. We’ll fix it,” I hear myself saying, though if this was anyone else, I would have already called the police and told him to collect his belongings.

“It can’t be undone!” he says, on the verge of tears.

“It’s just a plant, Mr. Schultz.”

“It’s ruined.”

“It wasn’t even real.”

“It’s ruined, can’t be undone…”

Poor Schultz, all that pent up hostility and sexual frustration, finally allowed out and – for what? To beat a plastic fern against the scuffed and stained tile floor of his own beloved hotel lobby…

“Mr. Schultz, we’ll fix it.”

I’m already erasing the video footage of the incident. And really, what the hell? Our system is so old it malfunctions at least once a week. Why can’t this be one of those times? Last month, we failed to turn up footage of the parking lot after eight cars had their windows busted by junkies rifling through the gloveboxes for change… This is just a plastic fern.

So I narrate my illegal act. My probably ill-advised fireable offense. Schultz looks at me as if he can’t understand. On some level, neither can I. But once begun…

“No more evidence, Mr. Schultz. It’s fine.”

He points helplessly at the fern, the brown styrofoam sand, the green plastic remnants, the broken pot…

“Yeah, we’ll have to clean that up. Goddamn junkies. I shouldn’t have let that guy in. Good thing you helped me kick him back out.”

He looks at me with wide uncomprehending eyes. Christ, I think he’s on the verge of tears.

“I’ll get a couple of garbage bags. If you don’t mind helping me clean up.”

He blinks his emotion away, shakes his head a few times, and rolls up his sleeves in preparation for the coming labor. Pretty soon he’s into the spirit of the thing, rehearsing his tale of junkie encroachment and mayhem.

“I knew right away he was no good.”

“I didn’t see it, Mr. Schultz.”

“Could see he was no good. The way he threw that pot over and shook the fern out. Onto the floor! Onto the floor as if no one else was here. As if this was his own backyard. Some people just can’t help themselves…”

**

After our adventure I didn’t see much of Schultz for a while. Maybe it wore him out. Maybe he was ashamed. But for a few weeks he avoided the lobby, and newspapers sales dipped accordingly. Often, to my surprise, I found myself thinking of him. Wondering why he didn’t come down. When easy laziness crossed over to weary boredom, I’d wonder when the stubby old man would be back at his perch by the window, tittering and guffawing at the absurd news of the day. One night I even cracked a window, as if to summon him!

At the same time, I was angry at myself for caring. I’d taken the job to avoid people, to sit in the silence of the night, alone and without other voices. Like Mr. Schultz’s “clean” quarters, I too believed in a kind of hygiene. A moral hygiene, you could say… solitude and silence, distance from the other yahoos.

So I’d put these thoughts aside and try to focus on something specific and distracting – some book I was reading, some vision I’d had that day while out walking. But I couldn’t stay focused for long. As if suffering from a sickness of comprehension, some mania for abstraction, for seeing the whole, I kept picturing myself in context, and Schultz along with me. I’d see myself sitting in the dusty lobby, and then I’d see the rest of the hotel, and then the hotel as if from above, in the context of the whole neighborhood – what was left of it! And I’d begin to chart the intact parts of the neighborhood against what had been demolished, replaced, left to rot… And eventually I’d imagine the neighborhood within the rubble of the whole city.

And then, worse still, I’d people my dreams, until I could see neighbors, co-workers, the junkies who slept on the church steps at the end of the block, the panhandlers who begged at the entrance to the bodega, the firemen endlessly washing their trucks across from city hall, the hookers under the overpass, the Johns cruising past in their cars – all of it, the entire absurd menagerie, everything that was beneath notice, I’d observe it, catalogue it, note it down into the vanishing journal of my mind – the blank, endlessly renewed blankness, which, in spite of myself I kept covering in notations of every kind, kept soiling with observations, and against which even a doubled dose of vodka in my coffee could not prevail.

What was this? This distasteful interest in my city, in the vanishing world around me, in Schultz of all things! I couldn’t stop contemplating him. Schultz tucked into his tiny apartment on the fifth floor, cleaning obsessively, disinfecting the counters he never used, wiping down the toilet, changing his sheets, sorting his loose change into baggies to contain the germs… Schultz at home, in his decaying city… and me wandering, walking pointlessly through it… the bum builder fighting off gulls or clawing at the lice in his filthy tent, drinking glumly by the dirty river, in the despicable Spring evenings.

But soon the whole spectacle would become too much for me, and, exhausted, I’d turn back to my book, my daydreams, and the vodka in my coffee, finally worn out enough to focus, hoping merely to outlast the still endless overnight April darkness.

And then eventually he started coming down again, resuming his routine. The laundry, the “clean” quarters, the crumbs of conversation as prelude to newspaper purchases… The muttering and even again giggling beside the window. His window. Everything is as it was. The lobby is now of course one fern short – the GM bought my explanation, but he didn’t buy another plant. But aside from that small detail, it’s as if nothing has changed. And maybe it hasn’t. Can’t things be swept under the rug? That’s what we did with most of the styrofoam dust!

“Do you ever think about leaving the city, Mr. Schultz?”

Schultz squints at me, seems barely able to contain his anger (and it pleases me to see him so riled up again). “Where would I go?” he demands. “What would I do?”

I imagine he’d do much the same as he does here – tap around his room, clean and clean again, eat, sleep, think about leaving, do his laundry, run back upstairs until the middle of the night, and then maybe go sit in the lobby… Ahh, but would there be a lobby? Maybe just some old folks milling around the entrance to a nursing home. No one but the dying and their anxious families. Or bored families. Resentful families.

But it’s like old Schultz can read my mind. I was thinking he couldn’t possibly understand my meaning, the implications… but he grasps them and much more. He understands the entire problem. The entire situation.

“I’m going down with the ship,” he says simply.

And of course he is. Even though he rarely leaves the hotel, he needs this city. He’s been here this long, he might as well finish out the loop. He grew up when it was thriving, watched it decline, flounder, try to recover, and ultimately sink down in defeat. He’s going down with the ship.

Anyway, there’s something to the life one lives in these circumstances. You have to go out in the daytime around here – the night is too dangerous. It gives you a sense of rhythm that whim can’t overcome. Then there’s the hint of fear in the air at all times. You remain at attention! It energizes you for the sake of self-preservation. No phony resolutions here – you have no choice. You’re on your toes, aware of the others. Really, the whole thing deepens your awareness, prods you to greater acts of comprehension.

And while you’re staying alert, you sharpen your memory as well. You walk in the shadows of the newer buildings and realize they’re the same as the shadows of everything that’s been torn down. You remember the restaurant that used to be on this corner, the butcher shop that was next to it before the whole block was junked. I bet Schultz gives himself a tour in his imagination every time he walks through the neighborhood. He pictures long gone alleys, now ruptured and filled in with parking lots. He sees the crowds that used to fill the shopping streets, now vacant below crumbling facades.

Why would he leave?

There’s nowhere to go, and no reason to go there. There’s nothing to do, nothing to be done, and no one to do or forbear doing it. No, you can’t just leave the city, as if the things you’re leaving had been part of a local affliction. You live in an age where nostalgia and rage seem inescapable, seem the only justified emotions, the only responses not weighed down with insincerity and delusion. Go down with the ship – at least then you know what and where you are. I’ll do the same, though my memory of what’s been lost is shallower than men of Mr. Schultz’s day. I have to fill in imaginatively what they can simply recall. I’m not sure if that increases or decreases the pathos, the melancholy tone of the whole thing, but either way, there’s nothing else to do. No, I won’t leave either.