T.E. Hulme on the Origin of Left and Right

“Hulme is classical, reactionary, and revolutionary; he is the forerunner of a new attitude of mind, which should be the twentieth-century mind.” – T.S. Eliot, 1924.

“It is difficult for [the left] to understand a revolutionary who is anti-democratic, an absolutist in ethics, rejecting all rationalism and relativism, who values the mystical element in religion ‘which will never disappear’, speaks contemptuously of modernism, and progress, and uses a concept like honour with no sense of unreality,” – T.E. Hulme, Preface to “Reflections on Violence”

Introduction

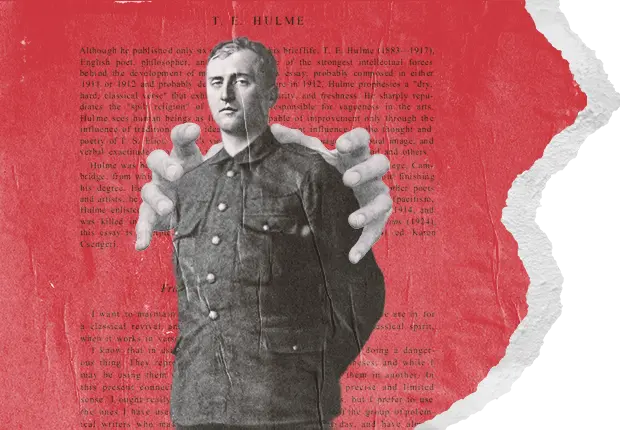

T.E. Hulme was a British philosopher, poet, critic, and soldier, whose work and relations greatly influenced the birth and development of modernism and the philosophical underpinnings of right-wing radicalism in the English speaking world. Had Thomas Ernest Hulme not been blown to irretrievable pieces while reportedly “lost in thought” in the trenches of Flanders four days after his 34th birthday in 1917, he almost certainly would have gone on to be one of the founders of a unique British fascism. Though Hulme was mainly an art critic and writer on philosophy, this claim is entirely supported by even the most cursory reading of Hulme’s political work and will be further elucidated in this essay.

Many readers might be familiar with the work of French political theorist and revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel and the school of “third positionist” political philosophy, but few are probably aware that T.E. Hulme was the first man to translate Sorel’s seminal “Reflections on Violence” into English. Hulme’s original translation and his preface are maintained in Imperium Press’ edition of the work which I would highly recommend to anyone interested in the intellectual genealogy of rightist thought. Owing to his personal talent as a philosopher and political thinker, Hulme’s eight-page preface to the work is more than a simple elucidation of the original text, but instead represents something of a personal manifesto of his own political wisdom. In it he imparts ideas of his own as drawn from previous works and heralds the beginning of a new state of mind that must come to bear if a “regeneration of society is to occur.”

The Left and Right

Hulme’s preface begins with a bold challenge to socialists, liberals, and progressives that they are completely out of their depth when it comes to critiquing, let alone understanding, radical rightist thought at the beginning of the 20th century. Anyone in the modern day who has any understanding of leftism and radical rightist thought in the 21st century will have immediately noticed a similarity here. You are right to do so, and it is good that you have, for the political battles Hulme and his fellow travelers fought 110+ years ago are the same that we are fighting today, and historical precedent is always fruitful instruction.

Nevertheless, Hulme identifies that the general incomprehension of Sorel’s work among left-wing critics hinges on the fact of Sorel’s separation of two elements inherent to socialism, these being the working class movement (which Hulme shortens to “(W)”), and the system of ideas that go along with it. Though Hulme calls the word ugly, he categorizes this system as “ideology” or “(I)”. In understanding Hulme and Sorel’s work, left-wing defenders of socialism find a stumbling block in Sorel denying “the essential connection between these two elements [and] even asserts that the ideology will be fatal to the movement.” The purpose of Sorel’s program is to reject the progressive and pacifistic ideology (I) that is too often hitched to the working-class (W) mass movement of the people. Already here one can start to see the origin of a rightist interpretation of socialism that will eventually manifest in Italian Fascism and National Socialism.

Like all big thinkers of the era both on the political left and right, Hulme understood that Europe was in a state of decay from the excesses of modernity and that something radical must be done to resuscitate it. In opposition to Fabian Society types of liberal socialism that could recognize the problems but had less radical proposals than groups like the Bolsheviks, Hulme said that “the regeneration of society “will never be brought by the pacifist progressives.” Anyone already familiar with Sorel will know how big of a role action plays in bringing about desired political ends. Sorel’s work preaches a philosophy of action, hence the titular “violence,” and thus naturally stands at odds with pacifistic socialism. This worldview a liberal socialist struggles to comprehend, and can do little more than paint it as reactionary and confabulate ulterior motives for its expressed goals.

In an evergreen statement, Hulme says that when a democrat, by which he means libtard, encounters this new state of mind, they conveniently dismiss it as “springing from a disguised attempt to defend the interest of wealth.” For anyone in right-wing circles long enough, this should sound exactly identical to the false canard that “fascism is capitalism in decay.” Put simply, such accusatory reactions arise from the general inability of left-wingers to intellectually grasp anything reactionary, anything that denies the progressive view of history. When encountered, Hulme says, the progressive mind “must call to its aid the righteous indignation which every real progressive must feel at the slightest suspicion of anything reactionary. Instead of considering the details of the actual thesis, the progressive prefers to discredit it by an imagined origin.” Sound familiar? In our current decade, such imaginary origins don’t even need to be confabulated—though they are. Instead, in our day, all that needs to be said to discredit an idea or held belief is to accuse the holder of being a racist or a “Nazi” and societal leprosy infects that person until they’re socially outcast and completely contemptible. How amazing it is to hear of the same situations playing out identically today to how they did a century ago.

The inability for the left to understand the radical right has to do with unfamiliarity. Whereas today the left simply has no experience with rightist ideas from the mouths of the thinkers themselves and has instead been inundated with facile criticisms from the intellectually stifling environment of ideologically captured universities, a century ago rightists dominated the avant-garde and were politically novel, radical, and vibrant. The ideas were unfamiliar, and there is a comfort in dismissing the unfamiliar, as Hulme quoting a mocking Sorel puts it: “You see there is nothing in it. It is only our old adversaries in a new disguise.” The problem inherent in the left-wing understanding has to do with an ideological stubbornness inherent to progressive thought which sees their ideas as right and true on the basis of their contemporaneity. When your political beliefs revolve around a progression of history from the very terrible to the gradual emancipation of all the very terrible things that made it so, denying such progress is like denying history itself, it is like denying chronology. As Hulme says, coming up against this strand of anti-democratic thought “feels just as if some one had denied one of the laws of thought, or asserted that two and two are five.” This is because democratic thinking is such that liberals cannot conceive of the ideological (I) element to democracy (this being liberal progressivism and liberation theology) being able to be divorced from the workers, or “popular” (referring to the masses) element (W). Hulme again speaks to this, saying “[the democrat] has not yet thought of democracy as a system at all, but only as a natural and inevitable equipment of the emancipated and instructed man.” To the liberal, liberal ideology must be an inevitable way of thinking that follows mass politics and universal suffrage.

According to the liberal, an illiberal democracy is an oxymoron, one could never express the true will of the people (the real definition of democracy) in an authoritarian state, despite the fact that Orban’s Hungary (which he explicitly calls an illiberal democracy), or Hitler’s Germany (democratic authoritarianism) are probably the two most popular (see: reflecting the will of the people) governments of their respective decades. Liberal democracy, inversely, is the true oxymoron, for the system of liberal rights and protection of individual privileges comes into conflict with the overarching protection of the interests of the majority, which inevitably will conflict with the rights of the individual. Anyone who has read the work of Carl Schmitt, particularly his “Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy” will understand this well.

The Origins of Progressivism

Of the particular nature of late 19th century liberalism, Hulme explains it not through examples and definition but a genealogy. He dates “this democratic ideology” to the beginning of the 18th century Enlightenment and making it fundamentally an expression of bourgeois liberalism. Hulme speaks only dismissively of these origins as they exist today (c.1915), calling it a body of “middle class thought dating from the eighteenth century” that has “no necessary connection whatever with the working-class or revolutionary movement” of the present.

“Liberal socialism is still living on the remains of middle-class thought of the last century…and in being [pacifist, rationalist, and hedonist] so believes itself to be expressing the inevitable convictions [progressive historicism] of the instructed and emancipated man, it has all the pathos of marionettes in a play, dead things gesticulating as though they were alive.”

Put simply, liberalism in the modern era has no context. Liberalism was made to defend the property interests of White, enfranchised men against those of a growingly cosmopolitan, rootless aristocracy. It had no context in the burgeoning era of mass politics and mass movements that spawned at the dawn of the 20th century. The history of both left and right radical politics in this era was the seeking of a formula to communal oneness, not increased individual atomization. It sought to be part of something again, not a cog in a machine but a chain in an order of being. The default state of the European man in this era who had his head above the radio waves was idealist, nationalist, mystical and calculating, and prone to culturally revanchist sentiments.

Classicism and Romanticism

After this historiographical look at the origins of liberal socialism, Hulme then endeavors to understand the attitude from which it springs. Now this will begin a summary of one of Hulme’s most famous insights, the distinction between two political, artistic, and religious frames of mind, (or as Hulme calls them, temperaments): the classicist and the romanticist. While most elaborately treated in his 1912 essay “Classicism and Romanticism,” in the Preface, he gives a short summary as well:

“All romanticism springs from Rousseau, and the key to it can be found even in the first sentence of the Social Contract — ‘Man is born free, and he finds himself everywhere in chains.’ In other words, man is by nature something wonderful, of unlimited powers, and if hitherto he has not appeared so, it is because of external obstacles and fetters, which it should be the main business of social politics to remove. What is at the root of the contrasted system of ideas you find in Sorel, the classical, pessimistic, or, as its opponents would have it, the reactionary ideology? This system springs from the exactly contrary conception of man; the conviction that man is by nature bad or limited, and can consequently only accomplish any thing of value by disciplines, ethical, heroic, or political. In other words, it believes in Original Sin. We may define Romantics, then, as all who do not believe in the Fall of Man. It is this opposition which in reality lies at the root of most of the other divisions in social and political thought.”

The progressive liberal, the leftist, the communist, do not only “believe in” this romantic conception of man as a limitless individual twisted by oppression, capable of great things if only they can tear down all the restrictions of society that stop them from reaching a utopian existence, they are actually temperamentally oriented towards that vision of the world and man. Now while Hulme does not explicitly say this, we know from studies today that political leftism is largely a biological phenomenon, and that conversely, a conservative orientation towards the world is also reflected in biological realities. This conservative orientation regards man as a fixed and limited individual living in a fallen world.

Conservatives being usually more religious both as a matter of faith and as a political ontology gives credence to Hulme’s highlighting of the importance of Original Sin in this equation. Though the starting outlook is negative, this classical man believes that through discipline, order, and tradition that “something good can be made of him.” This is where the conservative gets his reverence for the past and his belief that the social order is functioning well enough to sustain him and his family. It is when discipline erodes, order gives way to the disorder of revolutions and rapid change, and tradition is trampled on deliberately by spiteful bad actors and the inevitable “modernizing” of time that the conservative begins to be dissatisfied with the way things are going and starts to realize something must be radically remedied. The right wing man is thus the man of this disposition who is disillusioned with the promises and direction of the modern world and seeks political action to bring about this “regeneration of society” so as to reestablish a connection to tradition and community to be able to live historically once again. The inspiration which must proceed this necessary action Hulme calls heroic, and is akin to what some right wing activists today call “romantic.”

Hulme says, “the transformation of society is an heroic task requiring heroic values… virtues which are not likely to flourish on the soil of a rational and sceptical ethic.” On the contrary, says Hulme, this regeneration can only be brought about by “actions springing from an ethic which from the narrow rationalist standpoint is irrational, being not relative, but absolute.” Hulme’s attitude towards ethics being either absolute or relative is something of a matter of contention, as he has written things which seem to suggest opinions to the contrary in different locations. Parts of our ideology that liberals call irrational is better understood as pre-rational. Pre-rationality is a system that we know to be true by instinct and other natural, non-psychological inclinations. Humans have urges to protect or fight, or aesthetic judgements or disgust responses that originate not in the rational mind but from somewhere pre-rational, a place where logic is applied afterwards as a matter of justification. This note on irrational, absolutist regenerative action is not only Sorelian, but should be recognized as broadly right wing as well. Hulme contrasts this view with the progressive view of reformists: “The transformation of society is not likely to be achieved as a result of peaceful and intelligent readjustment on the part of literary men and politicians.”

Absolutism and Relativism

An expansive footnote in the text makes an allusion to artistic styles of different nations. Hulme says that as European man started to appreciate:

“Egyptian, Indian, Byzantine, Polynesian, and Negro work as art and not as archeology or ethnology… [This] demonstrates that what were taken for the necessary principles of aesthetics are merely a psychology of Classical and modern European art, [and] at the same time suddenly forces us to see the essential unity of this art. In spite of apparent variety, European art in reality forms a coherent body of work resting on certain presuppositions, of which we become conscious for the first time when we see them denied by other periods of art.”

Hulme in this footnote also makes the point that things once taken for granted in Western art—things like symmetry, perspective, and realism—once thought to be universal standards, were discovered through confrontation with the Other to be expressions of the uniqueness of the European mind. So too in our day are we starting to see the incompatibility of certain populations in Western society and are now starting to consider that concepts like individual liberty, freedom of speech, high-trust environments, and queuing for the bus are temperamental concepts of unique European psychology and not for universal export. John Adams once said that the American system of governance could only work with a moral people. It perhaps would have been better for him to have said a European morality, for we are seeing the American political system (and those in the wider European world) coming apart at the seams through it being wielded by non-moral, non-Europeans.

Hulme as Prophet

Hulme is a herald for the coming revival of the classical spirit. In literature such a prediction could not be more accurate, as he foresaw the explosion of literary modernism and the hard, pessimistic, and tradition-affirming work of Eliot, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald which would go on to dominate English-speaking literature for decades. But further than this, Hulme stands alongside his political influences Sorel and the men of the Action Francaise, particularly Maurass and Lasserre, as the harbinger of proto-fascism. As he himself describes his revolutionary attitude—“anti-democratic, an absolutist in ethics, rejecting all rationalism and relativism, who values the mystical element in religion ‘which will never disappear’, speaks contemptuously of modernism [not to be confused with his literary movement], and progress, and uses a concept like honour with no sense of unreality”—in Hulme there exists a forgotten reactionary who contemporary right-wing radicals would do well to rediscover. The regeneration and subsequent transformation of society will not come about through reform-minded conservatives or so-called “racist liberals,” but is only possible through a return of the classical spirit. As Julius Evola commands: “Be radical, have principles, be absolute, be that which the bourgeoisie calls an extremist: give yourself without counting or calculating, don’t accept what they call “the reality of life” and act in such a way that you won’t be accepted by that kind of life; never abandon the principle of struggle.”