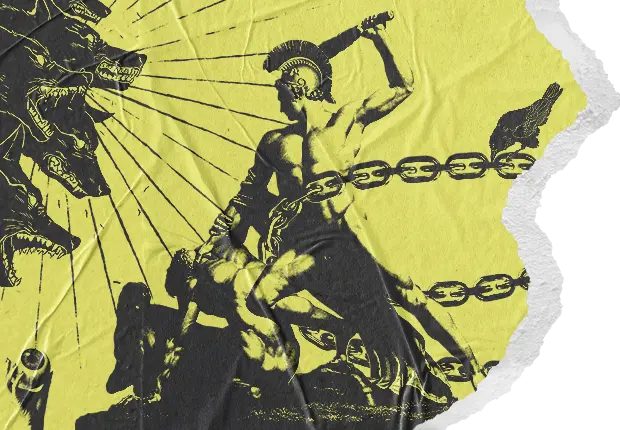

The Chains of Theseus

I

His vision spun in ribbons and rings. He was adrift on the frigid, black-hearted sea, and the howl of a distant storm echoed in the beyond. Beneath him spread the tumbling waves—he plunged his hands into their depths, but the sea was not cold; no, it was warm, warm and biting–

“Hey! Do that one again. And use more soap this time.”

Throk stood before the sink, up to his forearms in soapy water, vaguely aware of his mother reprimanding him for failing to clean one of her china plates. There were dozens of dishes to get through—his mother had entertained her coven last night, all aging, shrivelled crones with clawed nails and voices like strangled crows. The duties for cleaning, needless to say, fell upon Throk, while his mother texted those same women from her little black box with tales of his buffoonery. He could only imagine the laughter as they perused those messages. Caw, caw, caw!

Throk stood in a daze, soapy water cracking his hands raw, plastic sponge and steel wool scouring the last scabs of duck pâté from the returned plate. His mind wandered, circling around old memories like a wary panther, gripped in the doubt that something was not right, not right at all.

He had once been a warrior of great fame, born to a mighty chief. His earliest memory was the time his father had brought him a caught rabbit, and bidden the young Throk, aged three, to kill and butcher it himself.

Thereafter his will and body had been wrought in the iron hills and dark forests of the North. By his eighteenth summer, none in the tribe could match him for strength. By his twentieth, he was their foremost warrior, and had led them to many victorious battles against enemies fair and foul. When he thereafter took to wandering, tales of his exploits were told in hushed whispers by everyone from hunters in their elk-hide tents to ploughmen in their mud-brick taverns. They all knew his name; they all feared his name.

Yet here he was—Throk the Untamed, ravager of men and ravisher of women, in the house of his mother, washing dishes.

Throk wasn’t sure how it had happened. Certainly, there had been no sinks in his tribe, let alone ‘soap’. His mind, dulled and foggy, was beginning to lose track of the threads of his life. But for now, at least, he knew he had been Throk of the Merciless North, and now was not.

“Better, Throk, better” cawed the wizened hag. This woman, with her hooked nose and sunken features, summoned no recollections of his past.

“Now hurry up, or you’ll be late for work. The roads are icy, so let your sister drive you. She knows what she is doing.”

II

His mother bundled him into the car, a contraption the colour of unnatural iron. He had to hunch over to fit, and he felt repulsion at his own mass. His sister sat in the driver’s seat, smiling patiently.

“Put on your seatbelt,” cawed the Mother, “And don’t forget to wear a mask—I don’t want to get sick. Strain one-two-eight is all over the news.”

With the growl of a sickly beast, they began to move.

Throk looked about him. He was in a cage, every surface a pallid, rough material that reeked of mockery. His torso was bound to an achingly soft seat, but he found he had not the desire to free himself. Beyond his cage, he could see the land pass by, the same dwellings of grey stone repeating over and over. Then they came out onto a thoroughfare, and they were instead surrounded by other cars, clogged on the concrete road like a river of tar. The air now held the scent of smoke, but acrid, corrupted, like the noxious pits of the black mountains. Within each car was a person, or two people, their glazed eyes watching the machine in front of them. Throk wondered, idly, if they felt as he did.

When Throk had come to his sixteenth winter, he had left his tribe to spend a year alone in the wilderness. He recalled one night when, spear in hand, he had made the mistake of stalking the same deer as a young sabretooth.

He heard the tiger a heartbeat before it pounced. He whirled, blocking the deathblow with the haft of his spear. His life was saved, but his weapon lost, as it spun away into the undergrowth. At once the tiger was upon him. It was not yet fully grown, or his bones would have been crushed in that moment, but it was more than large enough to barrel him over and pin him to the ground.

He caught the gnashing jaws in his hands as the beast’s claws dug gashes into his chest. Raw pain. Swelling blood.

Throk kicked his legs, and found purchase. With a heave of strength he sent the tiger tumbling away. Faster than a thought— for he had no time for thinking—Throk was on his feet. The tiger recovered, pounced—but this time Throk was ready. He ducked beneath the open jaws and grabbed hold of the cat’s forelegs. He surged upwards, found his mark, and with his own gnashing teeth tore out the sabretooth’s throat. Hot blood sprayed his face; and he threw the tiger’s spasming body to the ground.

And Throk stood there, triumphant, chewing on the sabretooth’s flesh, its life-force dripping down his jaw and fuelling his soul. That night, he skinned the beast, and kept its hide as a trophy. He wondered what had happened to it.

The deer, of all things, escaped with its life.

“Let’s put on the radio,” said his sister.

Voices assaulted his ears like a squabble of harpies. Cases of latest strain up by two hundred… still they refuse to be vaccinated… rumours of permanent side-effects have been fact-checked false by our team of experts…

Throk looked across at his sister. He knew this woman. She had once put out the eyes of an interloper with a carving knife. Now she too hunched in her seat, tutting and commenting on the voices from the radio.

“That’s terrible… how awful… something really should be done about those people.”

They were overshadowed by more buildings now, but these were tall, crowded, and concrete. The barren trash-strewn roads about their eaves were mostly abandoned. Only a few people braved the cold dead air, heads down and shoulders hunched. Many of them wore strange bands around their faces, and it struck Throk that these people were slight, almost emaciated.

Defence Secretary blames toxic masculinity for the lack of cisgender males in the armed forces.

“Oh, I love her. Such a girlboss.”

He had fought beside many great warriors in his time, but none so treasured as the brothers of his tribe. One time, they had slain a mammoth by leaping upon it from the trees above; another, when a rival tribe had raided their camp at night, they had rallied and driven out the invaders in a crushing victory. He recalled in particular how his cousin had single-handedly slain the enemy warleader.

Man arrested for stabbing last night… claims self-defence.

“How terrible. The streets just aren’t safe these days.”

III

Their car pulled to a stop outside a particularly ugly monstrosity, huge and towering like an obese giant.

“All right, out you get. Here’s your mask. And here, take some hand sanitiser. Oh, and your vaccination appointment is at five. Don’t forget, or mum will freak.”

The door shut, and the car pulled away. Without his bidding, his feet, leaden with resigned intent, carried him into the building.

Many people were within, hurrying from some place to some other. Behind a large sweeping desk were two young women, and he stared at their features, sensing he ought to feel something, but finding himself empty. Several people eyed him with suspicion, and he felt their gazes like hooks pulling on his bones.

He moved towards the elevator. Though this place was strange to him, his limbs knew exactly where they were going. The doors slid open like the portal to a fiendish temple, and he entered. Runes were arrayed on the wall, and he instinctively pressed the final one, bearing the numeral for fifty-six. Throk could not recall ever learning to read.

The doors slid shut, and suddenly Throk was trapped, closed in on all sides by the sheet metal cage. His mind reeled, and at once he thought of beating the doors with his fists, until he was rendered free, or broken in the attempt. Once, he had been thrown into a pit by a psychotic tyrant of the coast, to fight slaves and beasts until his death. After defeating half a dozen island ‘warriors,’ he had fashioned their rags into a rope and tied it to one of their spears. When his captor had come to the edge of the pit to insult him, he had harpooned the devil, dragged him to the floor, and taken the key from his corpse. Throk hated nothing more than a cage, and he would rather die than suffer one.

And yet, some part of him elated in the tiny space, all to his own, and waited patiently until the elevator had lurched to a stop and the doors jerked open. Deeper into the dread temple, thought Throk.

It seemed to Throk that he had entered into a prison. In the plastic and lifeless chamber before him were arrayed rows of box-like enclosures, with only one open wall. And yet, rather than bounding from their confinement and seizing their freedom, their inhabitants sat motionless before squares of unnatural light. He stared at them, men and women alike, hollow like corpses. Some of the women returned his gaze, skittish, fearful… and their looks filled him with the same self-revulsion he had felt squeezing into the car.

“Where is your mask?”

There was a man standing before him—or at least, Throk supposed it was a man. He was short, pudgy, with a head round and smooth like a goose’s egg. Two beady eyes stared at him from behind a pair of spectacles.

Throk fingered the mask in his hand and held it up. He could feel his will leeching into the fabric.

“Why are you not wearing it?”

Throk simply stared.

“You know you have been asked to wear it until you are vaccinated. This city has been plagued by pandemics for years and still you troglodytes won’t listen! It is people like you that make the rest of us unsafe.”

IV

Throk’s desk was right at the edge of the web of cubes, with its free side facing a barren wall painted the colour of a corpse. It was not long after he had sat down that the eggman reappeared.

This time, Throk felt a spark of memory—he had seen men like this before. Once, when he was still a warrior in his tribe, another race had migrated up from the south and settled in their territory. Hunting became scarce from the competition, and swathes of forest were cut down for their wide and crowded dwellings. The southern men were small, soft, and led by a coven of elderly crones; but they were numerous, like ants, and in victory were as cruel as a vicious child with a trapped hare. Twice, they had attacked lone hunters; once, abducted a group of women washing hides in the river. Something had to be done.

Throk gathered half a dozen of his tribesmen and set off down the mountain. This southern tribe was known to hunt mammoths in groups of thirty or more—a laughable excess, in Throk’s opinion. Nonetheless, it played right into his hands.

The ambush was easily sprung. Throk and his warriors waited among the rocks in a valley so steep it was almost a canyon. The foolish Southerners, following the tracks of a mammoth the Northerners had driven through earlier that day, were as oblivious as flies in a honey trap.

The first volley of arrows slew five. Three more fell before they could find cover. Then the bellowing barbarians were upon them, and every swing of his sword felled another hapless enemy. In a matter of heartbeats the entire hunting party was slain; Throk’s warriors had barely a scratch on them.

In the coming weeks there were more engagements like this, and every time Throk’s tribe was triumphant. This was their land; the Southerners, with their weak eyes and soft hands, didn’t stand a chance.

Then, when the outer parties had been vanquished, Throk led a full raid on their settlement. The Southerners had constructed it in their peculiar way, with rows of tree trunks fashioned into walls, but it availed them nought—they had not counted on the Northerners effortlessly scaling the palisades. The final battle of this war was hardly climactic—Throk lost three men of his two dozen; and the Southerners, already weakened, lost everything. Every last man was slain and left for the wolves. The fertile women were taken back to the tribe; the rest were not so lucky.

Later that year, the Northerners were blessed with a large migration of elk to hunt. Such was the way of the wild.

“In case you needed reminding,” said the eggman, “you’re behind on reports. Finish the ones you’ve got, then get started on these.” He dropped a stack of yellowed papers on the desk with a thunk. “If you don’t finish by Wednesday, Floor Fifty-Seven will want a word. You’re on thin ice already, Throk.”

V

The next hours passed in a haze. Throk’s fingers struck his keyboard, words appeared on the screen, and boxes on the yellow paper were checked. At one point, the eggman returned to peruse his efforts.

“You’re falling behind,” he said.

Later, he was in a small cafeteria with some of his colleagues. They each had a bowl of something like boiled cabbage they were poking at with a plastic fork, and were drinking coffee that looked and smelled like hot oil. A larger black box was propped up above them, and the talking image of a woman with loveless eyes was upon it.

Man arrested last night for stabbing is being charged with intentional homicide for the killing of two protesters. He claims they assaulted his store-front and were attempting to steal merchandise. The man attacked the protesters with a machete—one was killed, and the other is in critical condition.

“How awful,” said one of his colleagues.

“They’re just fighting for their civil rights,” said another.

“He should have butchered them both and displayed their flayed corpses as a warning to their friends,” said Throk. “What manner of hell is this where a man may not defend his land? You wretches abhor violence and death, blind to the necessary role they play in the balance of nature.”

At least, that is what he wanted to say. Instead, his voice betrayed him, and the words emerged in a squeaky rasp.

“That’s terrible,” said Throk.

VI

More people entered the cafeteria. They collected their plastic pots and styrofoam cups; they sat slackly in groups and passed mutters amongst themselves. The eggman also came, and with him was another: a middle-aged woman, tall, rigid, erect, with bell-like hair, thin lips, and stretched eyes. Pointing to Throk, she muttered something to the eggman. Then, the ooze of a man approached, and stood before the sedentary Throk.

“Throk. We have been receiving complaints that you have been staring inappropriately at our women employees. This is your one and only warning to control your behaviour, or you will be referred to Floor Fifty-Seven for disciplinary action.”

Once upon a time, Throk had come across a jungle temple of square-cut stone. It was the furthest south he had ever been, and the weather was hot and humid. In search of treasure, he had scaled the vine-strewn walls in nought but a loincloth, but had found something else entirely.

In the middle of a courtyard invaded by the surrounding jungle was a woman, naked and tied to a stone column. Around her in a circle lurked bowed, cloaked figures, chanting in a sorcerous language; warriors strange to Throk, with their grass skirts and painted faces, stood at the edge of the clearing thumping their spears on the ground. One of the cloaked priests approached—his form, like the others, seemed misshapen to Throk’s eyes, and when he cast down his cloak the truth of that was revealed—a horribly twisted body, malformed and scarred by disease and foul magic. Fully naked now, he held aloft a dagger and shrieked his cursed appeals.

The woman was not of the South, but of the North, her pale, exposed flesh quivering in weakness and fear, her golden hair drooped over her defeated face. Desire surged through his body, and he stole forwards.

Some amongst the southern cities called him the Fury of the North, and on that night he earned his name. With the stealth of a panther, the skill of a hunter, and the fury of a god he broke into the circle and set upon his foes. Though the warriors tried to surround him it availed them nought against the vigour in his veins; though the priests called wicked curses upon him it availed them nought against the bite of his steel. A night of blood unlike the temple city had ever seen, and at the end Throk, gouged and bloody but triumphant, approached the woman and cut her free.

She became his companion for many adventures. Great tales were told of the legendary warrior and his huntress queen. Throk wondered what had happened to her. He could not even remember her name…

Throk looked into the eggman’s fatty, glazed eyes, visions of those memories slowly fading away.

“Do you have anything to say for yourself?” said the eggman.

Muttering began around him. His colleagues were all watching, and every stare was a chain about his limbs. “What a creep… can you believe it… hope they do something about this…”

And in that moment, something curled up like a gutted vermin in Throk’s bowels, and his gaze fell to the eggman’s feet.

“I’m sorry… I’m sorry…” he pleaded, “I won’t do it again. Please, please forgive me.”

He heard the eggman smack his lips with delight. “You are not forgiven, but we will allow you one final chance.”

Throk the Imperishable, the Wind of Death, was defeated, and Throk the mild-mannered box checker was triumphant.

“I hope he learns his lesson,” someone said.

VII

The rest of the day passed in a blur. He sat at his desk, his body curled up to be as small as possible, and he checked his boxes and filed his reports. Selfishness, that was the problem. Everyone just needed to be more considerate. He was so thankful to have been made to understand that.

As the afternoon crept on, he knew that soon the time would come for his sister to arrive and take him to his appointment. His chance to finally demonstrate his remorse.

One of the office’s secretaries came to his desk. A quick glance at her face revealed her displeasure, and he quickly averted his eyes in fear. All possible thoughts of her beauty—or what remained thereof—were stamped on and destroyed.

“There’s a weird old man to see you downstairs,” she said. “Asked for you by name. You’d better go, he’s very insistent. Make sure he goes away before he causes a scene.”

Throk nodded, happy for the chance to prove his obedience.

“But don’t be long. You have reports to finish.”

“Yes. Of course. I’m sorry.”

He shuffled over to the elevator, hoping that nobody was watching him but knowing that they were. Down in the lobby, there was now nobody around, save for the usual receptionists eyeballing an old man lounging in the cushioned seats in the corner. Throk approached.

The man was a strange sight. Old indeed, his face and hands were crossed with weathered lines, but he was nonetheless physically imposing, with broad shoulders and a thick white beard bound into a braid. He wore a bizarre garment which seemed like little more than a dull green blanket wrapped and wrapped around his body.

“You have almost forgotten who you are, Throk,” said the man, “who you were born to be. You have not long left before you will forget completely.”

Throk blinked at the man. He made no reply but sat in the opposite chair. He could not shake the feeling that he had seen him before.

“You hold within you an ancient power that has all but left this world. You have yet before you a choice: to reclaim your soul, or to succumb to the miasma.”

The chains on his limbs were heavy, and he had hardly the strength to breathe.

The old man stood up now, and Throk saw he was tall indeed, a full head above the average man. His eyes had a steel to them, and Throk could not look away from that grim visage.

“This is it, Throk. Will you listen, or will you send me away? Will you return or will you die?”

One last memory came to Throk’s mind. He was a young boy, no more than six winters, and he was standing on an icy mountainside with his father. The sky was pure, noble blue, and the great forests of the North swept out before them.

“This is what is,” said his father, gazing out at the vista. “The world runs through our veins, and we run through the world’s. To run, to hunt, to fight, to love, to live—this is what it means to be alive, my son.” His father crouched, and looked into Throk’s eyes. “Do not ever let that be taken from you.”

Throk stood up to face the old man, who suddenly did not seem so tall.

“What must I to do?”

“There is something you need reclaim. On the forty-third floor of this building, your Master houses his collection. What you seek is at the very end. Enter in and reclaim what is rightfully yours.”

“How will I know what I seek?”

“You will know.”

“Thank you,” said Throk.

The old man bowed his head. “Go. You have little time, and I can help you no further. You are on your own now.”

Throk inspected the old Man’s face. “Who are you?”

The old man smiled. “Just a memory,” he said.

VIII

Throk arrived at the lift. He searched the buttons, numbered up to fifty-six, and found the one marked forty-three. For the first time that day, he was in full control of his body, though it still felt strange to him.

He felt totally lost as to what was going on. No further memories appropriated his thoughts. He was, indeed, alone. Visions of his colleagues’ disapproval flashed in his mind, but nonetheless he was driven onward. He had to press on, he had to find what awaited him.

The doors slid open onto a dimly lit corridor, almost barren of natural light for lack of windows. With uncertainty settling into his limbs, he crept out of the elevator. The corridor extended to his left, before cutting left again deeper into the building.

As he continued, his fear of discovery began to grow. Surely, the Master would have installed cameras to protect his collection. But it seemed that fate had one final card to play for Throk, for two steps before he rounded the corner there was a crackle and a fizz, as the corridor was plunged into gloom.

“What the-” came a voice from around the corner—the guard to his Master’s horde. “Damnit, electricity must have gone out…”

Throk crept forward. The guard’s footsteps faded away, presumably to turn the lights back on. But Throk preferred this gloom… the vestiges of natural light had not the harsh, unnatural glare of the building’s usual illumination, and he found he could still make out what was before him.

The door was locked. It crossed his mind that if he backed out now, he could still get away without being discovered. But his heart was set. He kicked the door, once, twice, and the flimsy half-wood construction clattered open.

Inside was a hall, plastered strangely in red velvet, and lined with glass cases. Inside each was a strange relic, and Throk observed them all as he padded onwards. A masked helmet, gold and shaped like the sun. A black flag bearing a skull and crossbones. An ancient, reptilian eye that stared at him in fixed gaze.

But it was the item at the far end that caught his attention. Displayed above the mantle of a black, dead fireplace, was a sword. The blade was straight, square until tapering to a point; the handle was bronze-wrought and inlaid with gold. Throk knew at once that he must take it. He reached out, grasped hold of the handle–

A flood of memories cascaded into him. Every action he had made, every notion he had thought, every passion he had felt surged through his body in that moment. Throk looked down. His hands and limbs no longer seemed frail, but strong and mighty, his body no longer repulsed him but filled him with vigour.

Like a thunderbolt the ancient past arrived all at once. And Throk remembered who he was.

IX

For the first time that day, Throk marched from the elevator with his head held high. His shirt and shoes had been discarded, leaving his chest as bare as his feet. The legs of his trousers were ripped up to allow him more agility, and his sword was concealed beneath the blazer draped over his left arm.

A buzz from his pocket. He reached in to find one of the small black squares; on its was illuminated the name of his sister, and the message: “Coming to pick you up in twenty minutes for the jab. Don’t be late.” Throk snarled, and hurled it against the wall. He knew sorcery when he saw it.

The office lay before him. Illuminated now only by the grey, filthy windows, it reminded him of a cave he had once come across. A whole tribe lived within it, but they could hardly still be called men. The children were wan and sickly, and the elders would not allow them to leave, trapping them with stories of fear and terror from the sunlit world.

Danger, yes… Danger was real. And nothing could be real without danger.

Gasps and wide eyes followed him as he entered that den of resignation. The eggman emerged from the cafeteria, black oil in hand, and blocked his path. Every person in the room was watching now, and the eggman sneered in the knowledge that he had their full support.

“What do you think you’re do–”

With an open palm, Throk slapped the drink from his hand. It whirled through the air and splashed against one of the strange screens.

“You will not speak to me again.”

The eggman blinked, mouth slightly open. “You-”

Throk took a step towards him. That was all—a single step—and the eggman visibly wilted before him. Throk almost thought he was about to melt into a noxious, gelatinous puddle. The eggman looked at the floor, and said nothing.

“Good. Now, you will take me to your Master.”

The eggman nodded and waddled away. Throk spared a moment to regard his audience, his so-called colleagues that had bound him in chain after chain. And he realised, as he looked into their eyes and saw little else but fear, that they were not his enemy. They were victims, victims of the elders who would rather rule amongst the broken than not rule at all.

He followed the eggman, who muttered under his breath. Throk knew he called for retribution against him, and the savage was greatly amused.

The eggman stopped before a door at the end of an unlit corridor. He opened it to reveal a stairway lined in red velvet. Floor Fifty-Seven. Without another glance spared for the creature by his side, Throk strode forth.

X

The stairway was long, wide, and dark. It rose to a thick wooden door, which was unlocked.

The portal opened into a study, its walls covered in that same red velvet. The far wall was one giant window, but the entering light seemed to be swallowed up by the air, so that the room was lit only with a dull, bloody glow. The walls were lined with shelves of black leather books inscribed with incomprehensible runes. In front of the shelves were half a dozen statues of disgusting, warped people, fixed in poses of utter pain and defeat, their bodies so twisted that Throk could not tell if they depicted men or women. The only other decoration in the room was a wide desk of dark, polished wood; and behind that desk stood a man.

He was tall, taller than Throk, and horribly gaunt. He wore a neat, form-fitting burgundy suit, and his dark grey hair, down to his jaw, was slick with grooming. His features were narrow, edged and hollow, and behind them were sunk two eyes an unnatural red.

“So, Throk,” said the man, his voice raspy, reverberant, and with the depth of ancient thoughts, “you have remembered.”

“I know you,” said Throk, “from the Temple of the Black Mountain. You were their high warlock.”

“In a manner of speaking,” rumbled the demon. Throk growled in recognition.

“Yes, I remember that night well. I slaughtered your priests, loosed your slaves, and buried your fortress beneath the fury of the mountain.”

“An unfortunate setback, to be sure.” The warlock smiled, thin and malicious. “But it didn’t matter in the end.”

“Your reign is over, demon.”

“Is it now?” The warlock’s grin was gleeful. He walked, almost glided over the floor to one of the statues. He stroked its shrieking face with a skeletal finger. “You see what becomes of those who would defy me. They become… nothing.” He looked at Throk. “Why are you here? What is it you hope to achieve?”

Throk’s reply was a determined growl. “I will slay you for what you have done, and return to my home.”

“No, you will not.” The demon walked back to the window as Throk’s eyes narrowed with suspicion. “See for yourself.”

Throk looked past him to the light outside, and he saw a barren wasteland. Row upon row of desolate stone structures, devoid of trees or other life. No open steppe, no great forests, no mountain air. Just the same malignant sea of dead Earth, pouring smog into the murky sky.

Behind it all, the sun shone pale and distant.

“There are no more wilds, barbarian. No battles to fight or beasts to hunt. Your beloved North, as you knew it, is no more, and your tribe is ashes on the wind. There is no place anymore for people like you. The sun has set on you and your people, and dawns on a new era of civilisation. You can do what you like, but it is already over.”

Hopelessness crept into Throk’s limbs. The sudden feeling of being totally, inescapably alone; the knowledge that he was lost, that there was nothing he could do but struggle until his death. And what was the point, really? Here he was, out of time, separated from everyone and everything that should have been beside him. He could feel the truth of the warlock’s words—this land, blasted and ruined, this was all that was left of his home. What was the point, when he had no hope of victory?

But the words of that ancient, long-lost memory returned to him, and echoed in his heart. This is what it means to be alive, my son.

Throk’s eyes narrowed on the man, and the despair he had felt before the warlock’s aura of confidence roiled and grew into anger, and hate.

“Enough of your words. This ends, now.”

“Why do you struggle? What hope do you have? We are inevitable, Throk.”

“And yet, here I am.”

And the demon’s expression changed, an edge of tension entering his voice.

“Here you are.”

Suddenly, the room was torn open by dreadful, awful, eldritch screaming, as the six statues exploded into motion. The first monster met with the cut of Throk’s sword, the blade plunging through its pustulous flesh, the monster shrieking as it fell. Throk’s fist crunched into the next; the blow was like punching mud, lipid meat sucking to his skin, but one of its eyes burst, and it fell to the ground in an anguished wail. The third creature slammed straight into his gut in its mindless fury and bowled him to the ground. Beyond the fight, Throk could hear the warlock chanting, preparing to cast his wicked spell.

The rest of the monsters mobbed him where he lay, bludgeoning him with their deformed, club-like appendages. Throk writhed like a wild animal; beating his limbs and ripping his sword in a savage bid for freedom. He felt the blade bite deep into the gut of one directly above him, and he heaved his weapon upwards, ripping through its innards and spraying him with a plunge of foul-smelling pus. A moment of space, and he seized upon it, rolling onto his stomach and scrambling to his feet.

At the back of the room, behind his desk, the warlock was finishing his chant. Threads of billowing red-black magic swirled around him, promising the barbarian’s doom. He had heartbeats, if that, and so he charged.

The monsters, maddened beyond all recognition of pain, had already recovered. The slammed into him, grasped at him, tried to drag him to the floor, but the mighty thews of his legs carried him forward. And just as the warlock wound up to utter the last forbidden word, Throk leapt with all his might and fury. He soared over the desk, casting off the monsters like so many broken chains, and plunged his sword into the demon’s heart.

The final syllable of the warlock’s dread spell caught in his throat. Black ichor oozed from the wound; the demon opened his maw to scream but no sound was made. Then his flesh sloughed away, as he melted around Throk’s blade and dissipated into ash. His creatures too began to dissolve, though far from writhing in pain they were still, almost blissful. And Throk stood alone in the demon’s lair.

XI

Throk looked out upon the concrete wasteland. He still was not sure how he had come to be here, so far away in time from the home he had known. Unlike the twisted monsters, the vista before him had not melted away when the demon had been slain. So if there truly was no way for Throk to return… then he would remain, and find adventure here.

After all, if this were indeed his fate, then perhaps fate had its own intent. Perhaps there was a purpose for the old ways to live yet. Certainly, in his hands the artifice before him would not prove as unyielding as it seemed.

And with little more than that, he left. His former colleagues watched him with awe, save the eggman who cowered in a corner. Each of them, though they knew not why, felt as if a weight had been lifted from their soul. For some, this levity begat terror; for others, it begat hope.

Forgoing the elevator, Throk bounded down the stairs, through the lobby, and out into the world. The sun, shining from a gap in the smog-fuelled clouds, no longer seemed so distant and wan.

His ride was not here. Instead, there was an azure-blue convertible, its keys still in the ignition.

“There you are,” said his sister, approaching from around the corner. “I’ve been looking for you. I’m parked just down the road.”

Throk grinned, grabbed her by the hand, and vaulted into the car. This time, he was behind the wheel.