The Radical Aristocrat of Hollywood

Jonathan Bowden said of Nietzsche, “His was an ethical superstructure for a radically aristocratic way of thinking which once existed in the past.” If Hollyweird ever had such a man it was John Milius, the man who refused the Hollywood Industrial Complex “norms”. A place where ethics are notoriously penumbral, a place that summons demons and thus by nature demands an equally savage spirit to battle against. That spirit sprung out of the abyss in the form of John Milius, a Bronze Age anachronism thundering, inveighing as only a righ- wing zealot can. “A lot of the principles by which I live were dead before I was born.” He smoked cigars inside Warner Brothers’s “smoke free” studios and offices. He refused traditional payment, demanding handguns and a SUV full of illegal Cuban cigars instead. John asserted his radically aristocratic way of living in a world where such philistine and buccaneering impulses were abhorred.

His was an impulse to action. It was the only true sense of being; he did therefore he was. He grabbed the bull by the horns, balls – anything – as long as his fists were clenched tight and he was engaged with life in a way that most men will not even consider a possibility for themselves. His was not a domestic life, but one which subsumed adventure, combat and physical stimulus. Faulkner said, “I believe that man will not merely endure, he will prevail.” With over 23 screenwriting credits to his name, most of which howled in the face the radical-left, Milius is a man who did more than prevail. Milius is a man who conquered.

Armed with a writing style heavily influenced by the muscular, Anglo-Saxon prose of Hemingway – terse and direct like a hard right to the jaw – Milius told the stories that he liked to read, steeped deeply in the lore of Homeric hero and hardy frontiersman. His was a type of syntax that once punctuated Hollywood’s most memorable scripts, written for the old gods of cinema, but which had fallen from favor. He was the resurrecting voice, which breathed life back into the sleeping giants of violence and vitality. He alone channeled the cold-hearted bastard, who blacked pity’s eye and shattered its jaw.

This concept of masculinity and storytelling came from Milius’s father. Dad Milius was a WWI vet and Harvard grad who would read John stories of Teddy’s “Rough Riders” and James Fenimore Cooper’s rugged frontiersman. When John delved into juvenile delinquency, his father sent him to boarding school in Steamboat, CO. Nestled within the Rocky Mountains was a school where John could check out a rifle, a horse and camping gear for the weekend. His naturalist spirit and his ability to write were fostered by a young, unorthodox teacher. Wayne Kakela was a recent Dartmouth grad who traveled the world by motorcycle, participated in biathlons (cross-country skiiing and rifle shooting) and encouraged his male students to engage not only with the great classics but also the great outdoors. While educating them on the likes of Homer, Hemingway, Faulkner and Conrad, he would co-opt their labor, for instance to craft an outdoor sauna.

After high school, John’s life purpose remained elusive until he wandered into a film festival while on an “endless summer” trip to Hawaii. It was here that he saw the films of Kurosawa for the first time, and his purpose became clearer. He returned to Southern California and enrolled in film school, a still nascent idea within Hollywood. As luck would have it, he graduated into a box office bear market; James Bond’s waifu fantasy You Only Live Twice delivered a 25% drop at the box office compared to 1965’s Thunderball and Hollywood was realizing that Connery’s hair piece was now as obvious as their inability to deliver results. Even legendary talents like Director Howard Hawks and John Wayne were doing retreads (El Dorado) of their own films, and still couldn’t match the box office power of the original (Rio Bravo, 1959). The studio old guard, etiolated and out of ideas, were willing to take a gamble on any writer who could help refill their empty coffers.

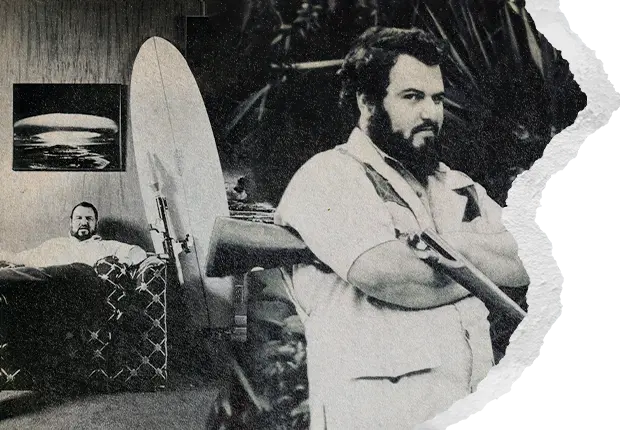

While Milius did pick up some part time work, it was mostly the NEET life of surf, sun and skanks that earned his full-time attention. While Milius was living in a bomb shelter under his landlord’s home, an agent across the street noticed the bombshelter bordello and its nightly cavalcade of bimbo habitues. He told John to give up surfing and sleeping around and get serious. John did not listen. A practicing Pagan, he named his surfboard Odin’s Arrow and earned the nickname “Viking Man” for his fearlessness on the sea, his captivating yarns around the fires of beachside barbecues, and his ability to take surf groupie brides. He found an altar at the foot of rolling Southern California pipelines. “It was like a religion…We were all living at an intensity which couldn’t be substituted by any drug, or job, or even women.”

John’s first significant success came in 1970 when he sold his script for Jeremiah Johnson. He earned $5,000 for the initial sale, but after being hired, fired, and rehired numerous times he ended up making close to $100,000 in total. With a newly formed mercenary drive to write, he exacted his tribute. Like an Alciabiades of Hollywood, he would hold up productions: if he was writing he’d torment directors, if he was directing he’d terrorize studio heads. The enfant terrible, the gadfly, the agent provocateur, no matter what they called him, he had writing talent and he delivered results.

Millius said, “(Director Sydney) Pollack always looked at me like I was crazy or was going to do something horrible or attack everybody or start gnawing human flesh.” It was this Dionysian spirit of chaos and frenzy that undoubtedly fed the crazed ravings of his fully scalped yet vitalistic character, Del Gue:

“These (mountains) here is God’s finest sculpturings! And there ain’t no laws for the brave ones! And there ain’t no asylums for the crazy ones! And there ain’t no churches, except for this right here! And there ain’t no priests excepting the birds. By God, I are a mountain man, and I’ll live ’til an arrow or a bullet finds me.”

Yet amidst his thundering, semi-non-sequitur tirades existed the Apollonian spirit of rugged individualism. It was John’s firm belief that purity inspired the mountain man’s savagery. Their desire for clean water, clear air, and unclaimed space revived long forgotten demands for savagery. It was savagery that asserted their place in that pure terrain. They were the first, and the first must always endure the bloodiest battles if they are to remain.

Embodying that type of ethos kept John constantly embroiled in feuds with the Hollywood elite. Milius saw Jeremiah Johnson and his struggle against the Crow in these terms:

“The feud will go on forever, and it makes both of them bigger and makes them live forever and also kills them. And these are the way all feuds are, the way the Hatfields and the McCoys are, the Capulets and Montagues, and the fueds in Borneo among the Dyaks. When I was making Farewell to the King in Borneo I’d ask the Dayaks, ‘What started this feud?’ and they’d say, ‘It doesn’t matter. The feud has been here since the time of God.'”

Milius was fully taken by the romantic notion of holding forth against an adversary, against insurmountable odds that would certainly end in death or at the very least loss of limb or physical function.

***

Milius was in the back of a sedan headed to Palm Springs to meet Frank Sinatra for the second time. In his briefcase was a handgun. Milius’s classic Smith and Wesson, four-inch model 29, which he had written into the script for Dirty Harry. Sinatra, who was lined up for the Harry Callahan role, had asked Milius to bring “the gat” that he was supposed to use in the film. When Frank saw the gun, after he had laced into his bodyguard for letting it get into his house unannounced (typical CA liberal, some things never change), he picked it up and acted out the famous line then set it back down. “Ooh, it’s a big one! Too big.” By the time Milius had driven back to LA from Palm Springs, Sinatra had decided he didn’t want to be in films anymore.

Now it was between Burt Reynolds and Clint Eastwood, and since Eastwood was younger, they figured he’d be more amiable when it came to doing scenes that Reynolds disliked (i.e. “stunts”). The studio took Eastwood off Jeremiah Johnson and went with Redford instead. Eastwood was moved to Dirty Harry. This affected the final script for Jeremiah Johnson (something about Redford refusing to eat livers) as Redford was imbued with a sense for the “greater good” as opposed to the savage realities of revenge films. The real Jeremiah “liver-eater” Johnson wasn’t as interested in “the beautiful and the good” as he was in removing his eternal enemy’s skin from its skull. He killed somewhere between 200 to 300 Crow Indians. He scalped them, ate their livers and lived till 90. He was the original “liver king” and spent nowhere near $11k per month on gear.

Milius was not interested in “good men” in the Aristotelian sense. Becoming good would only be accomplished by doing good, which could only be accomplished by beheading evil (preferably in public); there was no alternative. It was good men that let bad men off easy (compare wordcel Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction diner scene where Jules lets Pumpkin leave alive). It was good men who obeyed, and if Milius’s tumults with executives were any indication, obedience was not a behavior he was interested in cultivating, whether in his own life or in the characters which he brought to life on screen.

One such moment takes place between Harry Callahan and the lieutenant he reports to; a paper pushing mandarin who gloats to Harry:

“I’ve never pulled my gun, a fact which I’m quite proud of.”

“Well, you’re a good man, Lieutenant. A good man always knows his limitations”

Dirty Harry was excoriated by filmcel femcels like the New Yorker’s Pauline Kael, calling it a “fascist” film, while most on the Right understood that the Harold Francis Callaghan was a taller, quieter, vitalist version of Archie Bunker. As his partner says, “Harry doesn’t play any favorites! Harry hates everybody: Limeys, Micks, Hebes, Fat Dagos, Niggers, Honkies, Chinks, you name it.”

Harry Callaghan was based upon a Long Beach detective who told Milius, “When I’m put on the case, the verdict is in.” This detective was reported to have numerous notches on his own gunbelt. According to Milius “He was more out of LA Confidential than Dirty Harry, but he was an interesting guy becuase he was in his part time a dog trainer, and he was very gentle in training dogs.”

While the literati looked for any reason to trivialize and/or demonize white, middle class anxiety, Milius delivered a cinematic gladiator. Harry was the personification of the “Silent Majority”: a white allotrope made up of Scot-Irish heritage Americans and more recently arrived white, hyphenated Americans, all of whom needed a champion to wade into the “dirty” miasma of 1970’s lawlessness. Against a backdrop of violent crime (rape doubled and homicide grew by 76% from 1960 to 1970) this blue-eyed, brooding Achilles fights when he wants to and with methods he deems worthy despite the incessant bellowing of whatever Agamemnon is assigned to keep him under heel. Milius’s on screen worlds called for men like Harry; men who were beyond convention, beyond societal norms.

There is no better illustration of this than Milius’s retreatment of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in his screenplay for Apocalypse Now. Partnering with the auteur talent, Francis Ford Coppolla, Milius re-created Conrad’s Kurtz through Brando’s portrayal of a man who stared into the abyss and become the monster, a menace to the proper order of things. Kurtz admired the Viet Cong’s barbarity, their will to triumph. What the West saw as capricious Kurtz saw as an ability to constantly change in everything but their commitment. No measure was too murderous if it meant advancing self-determination. While the Left passively panned Apocalypse Now (among other reasons, they didn’t appreciate the use of Conrad, TS Eliot and Fraser’s Golden Bough as literary inspiration) they excoriated Conan the Barbarian, with one insider commenting to Milius that the “movie would have been very popular at the Nuremburg rallies in 1936.”

“Conan is a barbarian and most of his conflict is with evils that are wrought by civilization. He was a marvelous hero, like Achilles. He sulked and ran away and was force into things and had great rages and great melancholies. He is a character who relies on the animal, and I always believe that the animal instincts in people are the better part of them, and that civilizing instincts are often the worst part of them….contrary to what everyone else says, ‘Isn’t it better to think and evolve’ and all you do when you think and evolve is corrupt yourself…When the going gets tough, the tough get feral.”

Conan never becomes an impressive physical specimen without Thulsa Doom’s Wheel of Pain. In Milius’s case the ratings board assumed the role of Thulsa Doom and their numerous cuts were Milius’s own Wheel of Pain. The MPAA gave Conan an “X” rating three times, forcing numerous cuts particularly from the raid of the Cimmerian village. One such cut removes Conan’s mother hewing down several of Thulsa Doom’s men prior to being beheaded in graphic fashion, and a young Conan cutting the throat of a warrior. The novelization of Milius’s script gives the reader better insight into Milius’s true vision for his cinematic ode to Teutonic savagery.

One scene endured within pop culture’s consciousness long after the film had been forgotten by most. The “pit” where Conan cultivated his appetite for blood became inspiration for the UFC’s Octagon. When Milius cast Reb Brown in his movie Big Wednesday he didn’t realize this would put him in close contact with Rorion Gracie. In their basement dojo, Milius watched them dismantle men twice their size and began introducing members of his tight-knit Hollywood circle into a quasi-Fight Club. Married…with Children actor Ed O’Neill went on to receive a Gracie black belt, calling it the greatest achievement in his life other than his kids, and Milius’s own son eventually taught BJJ. Milius’s mind envisioned this blood sport as a spectacle of power. He envisioned it playing out in an arena where men could not escape, grappling for supremacy (originally surrounded by a moat of sharks). The early investors of the UFC hired John as their first creative director.

Milius’s last, best-known film is arguably one of cinema’s best depictions of a mannerbund taking on insurmountable odds. Red Dawn depicts a microcosm of society without laws or government which still maintains a semblance honor. While the original story centered on a Lord of the Flies plotline, with the boys inner depravity becoming the focus, Milius brought an ethos out of the chaos, while still reveling in the idea of lawlessness. He esteemed the concept of a personal Honor Code as more honorable than a society’s codification of laws:

“I’m not a reactionary—I’m just a right-wing extremist so far beyond the Christian Identity people… I’m so far beyond that I’m a Maoist. I’m an anarchist. I’ve always been an anarchist. Any true, real right-winger if he goes far enough hates all form of government, because government should be done to cattle and not human beings.”

In Red Dawn this honor is primarily underpinned by the martial execution of the “others” yet also rooted in the understanding that true glory, true honor is found in holding out to the last man, plunging sword until steel is broken, the way of the Samurai, the Bushido. Milius found inspiration through the classics and liked the “Song of Roland” in particular. This 11th Century epic tells of Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778. Roland’s fighting force of 20,000 is ambushed high in the Pyrenees by the swarthy Basques in retaliation for Charlemagne’s destruction of Pamplona. The Frankish commander and his men were cut off and, according to tradition, overrun by 400,000 Muslims. Yet instead of retreating from these insurmountable odds they fought until the last man, allowing Charlemagne to remove the majority of his troops from the treacherous mountains and regroup. Roland and his men established the chivalric model for a medieval knight.

There is no doubt that Milius was inspired to be the last holdout of a bygone era in film history; hardly remembered by most yet hardly caring if he is. Concerning George Lucas’s oft touted leveraging of Homeric heroes, Milius said,

“You know George Lucas talks about it all the time. He doesn’t know how to use it at all. He doesn’t understand myth at all. As illustrated by Phantom Menace. Writers who really understand myth don’t use it consciously. There are very few things that are truly mythical. There’s a lot of stuff that’s famous, but very few things that are the stuff of myth and legend.”

While Milius may never achieve the qualities of the former he has undoubtedly distinguished himself with all the qualities and investitures of the latter.