The Reactionary Imagination: A Review of ‘How to Start a Dissident Art Movement’

No ideas but in things—William Carlos Williams

“What was your Kronstadt?” was once a common refrain among old leftists, who often asked it with a note of chummy fatalism as a means of sounding out one another’s anti-Soviet priors. It referred to the 1921 rebellion of sailors and other naval personnel at the Kronstadt naval base on Kotlin Island, some twenty miles west of St. Petersburg, who, lead by Stepan Petrichenko, and disenchanted by the newly-appropriated and centralised power of the Bolsheviks—who had no qualms about wielding such state machinery—protested in favour of anarchical and social democratic reforms, among which were elected councils, embedded rights for the proletariat, expanded economic freedoms, and so on. Hailed once by Trotsky as “the glory and pride of the revolution,” the sailors of Kronstadt kept up their rebellion for little over a fortnight. After ten days of assault and bombardment from across the frozen sea, they then folded. It was Trotsky who had signed the order.

It makes sense that a betrayal such as this should have come to perform in the age of ideologies as something like an ineluctable theme or recurring motif, and that the ensuing decades were so arranged as to serve such idealistically minded men with its myriad variations. For the break between Trotsky and Stalin, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the staunched Hungarian Uprising of 1956, and the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia—each one provided another generation of leftists its Kronstadt, and each older member of the International Socialists further corroboration of their disunion.

No doubt many reading will have already drawn their own contemporary parallels, but I bring all this up not only to remind the reader how far he has come, but of where he started. Before Brexit, Trump, Floyd, Woke, et al. many of us were deeply committed—right or left—to the liberal priors imbibed in our youth. Such priors were not so rudimentary as to be brittle against temperamental deviance, and as such had their insipid flavours: Tory, Labour, Lib Dem, or any of the mainstream parties that make up the left/right divide among nations of the Western world.

We were not all unthinking in our positions, either. Many of us were even sceptical adherents to this state of affairs. Yet it was our scepticism that housed our deepest commitment. For whenever we felt, either in the news-cycle or in the sharper facets of our daily lives, that society was not living up to its august principles, we appealed to those same principles as means of critique. In the end, it was disillusionment not only with material short-comings—job positions closed off, projects curtailed, the atmosphere in which one lived slowly, then quickly, becoming hostile—but with these principles, which enabled so many of us, notable or not, to employ the phrase which has become common currency in recent years. Oh yes, we’ve all been “on a journey.”

The reader must forgive this little prelude. For it was while reading Mr Adams’s latest book that I found myself pondering these matters, if not for the first time, then certainly afresh. Even reading on the frontispiece that the selection of speeches and essays which make up the first half of this volume date from 2018 to 2025—the second half is a selection of letters dating from 2009 to the present day—one is inevitably reminded of the furore of madness which produced the characteristic din of that period. That the speeches and essays are arranged for the most part chronologically offers one of the chief pleasures of the book, which is to compare one’s own journey to that of its author. That it was a journey is in no doubt, something Mr Adams makes clear in his introduction:

“The drawback of printing older pieces is the reappearance of positions to which I no longer subscribe, as well as the presentation of arguments I would now approach differently. The pieces show my thinking evolving. This collection is an implicit invitation to consider how far you travel beside me. It may be that you would not go as far as me but find the pieces worthwhile as thought experiments.”

Indeed, we can chart the progression of Mr Adams from those few obstinate lines of the old catechism, such as when he mentions in an early piece of the collection, “I may not wish to attend such a dramatic performance [sympathetic to white nationalism] but I do not object to anyone writing, performing or watching such a drama. Yes, even another drama that was anti-white. . .” to where they give way to the more hardened, if sometimes reluctant, stances of the reactionary: “Even more painful, for an author who wrote an entire book advocating restraint and the preservation of ideologically objectionable art, is accepting the reality that many New Statues will have to go.”

Now, Mr Adams has written a number of polemical works that date back to those lamentable years when the phenomenon we are obliged to refer to as ‘Woke’ reached its highest pitch. It was in such books as Culture War: Art, Identity Politics and Cultural Entryism, Iconoclasm, and Women and Art: A Post-Feminist View, along with a number of brief pamphlets such as Abolish the Arts Council, that he staked his place among its notable critics, particularly so in the realm of the Arts. Yet How to Start a Dissident Art Movement is no mere jeremiad. After years of criticising that which has so incontrovertibly failed, the pieces in this volume point a tentative way forward for reactionary and dissident art, whilst dispelling as false dawns its incipient forms and modish postures.

The main concerns of the book may be split into those matters sociological and, if not anything so clinical as psychology, then certainly those challenges which pertain to the motivation of the contemporary artist, both of which stand as impediments once he has broken from the status quo. Two pieces in particular map out this territory, and it is perhaps no coincidence that they are the first two pieces in the book of significant length.

In the first of them, “Towards a Based Barbican,” Mr Adams outlines what a dissident arts centre could look like, what its chief attributes would be, and the means by which it would operate. These include a mixture of commercially minded productions, readings, and exhibition spaces in order to economically sustain a home for more radical artists and their work. As Mr Adams drily observes, such a centre “cannot rely solely on hipsters, fashion students and trendy sociology graduates; it needs elderly ladies who listen to Handel and watch Hamlet.” Well, God bless those elderly ladies! But it’s important to note that this is not merely an artist’s fever dream of the ‘build it and they will come’ variety, replete with the usual salivating and onanism over a model venue. (Mr Adams, thankfully, keeps such hopes pointed hearteningly toward earth). It is also a portrait of what social scientists of one stripe or another would no doubt call an eco-system. And Mr Adams is clear that no such dissident or reactionary eco-system is possible without ownership of the venue or property, for only by such ownership can any necessary ‘alternative economy’ at all flourish; one in which “Dissident artists should create their own networks, ones that retain and grow wealth within connected parts: venues, journals, books, exhibitions, artists, curators, writers, journalists, small businesses, audiences, etc.” All of this is mapped clearly onto the existing Barbican structure, and shows how these component parts would work in conjunction.

If it may be objected that the Barbican remains today as left-wing as any publicly funded institution, Mr Adams shows there is no issue for its being taken as a model. For chief among those prerequisites that he lists as necessary for such an institution to exist deal primarily with ensuring defence against subversion, either by purse-strings, or by disaffected liberals and leftists who have merely found themselves washed up on dissident shores. Such vigilance is well founded. For given the title of the book, it comes as no surprise that Mr Adams sees the advantages of artists working together in aggregate, and that the usual disdain for their curating posses is merely an unfortunate outgrowth from the familiar sophomoric image of the struggling artist becoming evermore attenuated in his garret. Nevertheless, to open a door to friends is always an invitation to those of more insidiousness intent. Yet the “critics as lice” attitude, which is still prevalent among many artists, is one Mr Adams has—whether gladly or not—necessarily dispensed with. Alive to the manner by which many contemporary artists struggle to negotiate the new world of digital patronage, it is only by the symbiotic relations of artist and curator, it appears, that he finds answers to today’s thickening malaise. That it is one that will require bricks, mortar, and property deeds, is doubtless as tiresome as it is true.

If all of this appears to omit the necessary imaginative element expected of such a volume dealing with cultural matters, then it is in the “The Coventry Speech”— which serves as the second of the two pieces forming a central spine of the book—that such men as would form an engine for this venue are described. Here, Mr Adams maps out against its better understood and often incestuous conservative and liberal counterparts the reactionary temperament, and by extension, its application to art:

“It seems that to me there may be no praxis for a reactionary, only doing. [. . .] The reactionary creator follows his instincts, hardly different to those of the huntsman. When he works, he gains an intuitive understanding of his tools and his materials. He knows his blade will twist in his hand, he can feel the grain of wood in the log, he knows the ring of true stone and clank of flawed stone when he raps it.”

If this has shades of Noble Savagery transplanted to Western shores then it is worth pointing out what differentiates such a conception from the more cultured “doer.” For Mr Adams, the reactionary is neither so weighed down by theory or the desire to have his ideological priors in order before acting, which mires him in the familiar cerebral labyrinth; nor is he the biblical Adam, who attends to everything for the first time as an untethered—culturally and temporally—naïf. Both in fact form a coherent whole in our contemporary culture, and are often present in the same person. You may well know the type. For he sits always like Buridan’s Ass, unable to move between pure thought and pure action—caught always between wishing to throw everything off and strut naked and in communion with his virginal self, or to take on as many articles of the mind as he can manage, always afraid he might be one idea short of conquering the dissonances of modern life.

That liberals and conservatives are equally represented along either end of this spectrum goes some way to explain how the reactionary sits apart. For certainly, in Mr Adams’s eyes, he is self-conscious, but not of his own consciousness; he attends to his craft—whether that be art, politics, even family-life—but only by an appreciation of its essentials, and never as an excuse to develop grand instruments by which he can endlessly explain his as yet consummated grand designs. His explanation is always his action, expressed through his art, his wielding of power, or his family; and that expression, as Mr Adams observes, which is redolent of the honed intuition, becomes “internalised as a kind of muscle memory, which links him with his ancestors, a profound instinct that has a poetry to which men respond.”

All this might explain the particularly recent, and particularly British, phenomenon of the revival of Italian Elite Theory, which winds its way lightly throughout the book. For such a theory—while it is a theory—nevertheless claims to explain politics by denuding it of all its ideological clothing, leaving behind only that which defines its operations: power.

By doing this for art and the artist, and boiling both down to their unique essentials (instincts, tools, materials), no doubt Mr Adams wishes to reveal the limits and freedoms otherwise obscured by current liberal perceptions of art. Cleared of its false paths and thickets of obscurantism grants the artist the knowledge of his foundations, a knowledge preserved by those essential means from the falsehoods manifest in the “larping” savage and self-consciousness’s pathological forms: “The maker, the doer, the reactionary man who understands the world through action learns the truth and knows that a lie will ruin the stone, break the tool, topple the structure, kill the man.” With such a structure thus intact, this orientation doubtless brings with it great strengths. For instance, the question “What was your Kronstadt?” can mean nothing for such a man. He can be betrayed, certainly, but each betrayal is its own event—just as is every achievement—and neither can be taken up as symbolic in an ideological battle, where it gets passed around and worn like stolen valour. His Kronstadt, in other words, can only be the Kronstadt, and if a Guatemalan or Chinese were to look upon his situation and heap upon it their own ideological load it would be axiomatically ridiculous. No, betrayal for him is everywhere and always of men, not of ideas.

If all this clears the ground of yesterday’s weeds, much of the remaining essays here concern themselves with pruning what has only recently sprung up. Here Mr Adams is at his best, running between the nascent dead-ends of traditionalism, “Trad,” the Localist or “Folk” Revival, and National Futurism, by turns taking a scythe to each one of these spurious shoots. That he is a generous and softly worded critic should not detract from his criticisms. Take for instance, his exposure of the kinds of woolly thinking and inherent contradictions characteristic of such movements as Anglo-Futurism (which to this writer has only ever appeared as Yimbyism with squirrels), and which are deployed deliberately to obfuscate their reluctance to face those issues implied by their own rhetoric:

“D’Albini writes that an ethnic Anglo who denies his culture can be treated as non-Anglo, which could give rise to the situation of a first-generation Indian admonishing an ethnic Englishman that it is he, the Indian, who is the truer Anglo.”

Undeterred by the haze of semantics such movements perforce utilise to obfuscate these shabby paradoxes, Mr Adams notes drily, “I am unpersuaded that in either theoretical or practical terms AF is distinguishable from civic-nationalism.” Not surprising then, that a movement which can stretch the delineation of Anglo-Saxon so thin as to become an idea, has a similarly attenuated aesthetic. Here Mr Adams touches on something which cuts to the heart of all “vibes-based politics,” pointing out how the “vibe”—whether it be AI generated squirrels or even the ‘Anglo’ identity as deployed here—inevitably becomes the chief aesthetic of all civ-nat conceptions of identity. For its oft observed shallowness can only ever result in a pervasive thinness, one as easily acquired and brandished as a passport: “In saying AF is a platform which any political party can adopt, AFs allow their vision to be deceptively appropriated by pre-existing organisations which caused the very problems AF opposes.” That he leaves it to a footnote—that most insouciant of assassins’ methods—to land the killing blow, by mentioning the recent excitement stirred among Anglo-Futurists when Robert Jenrick described himself as among their tribe, can only be described as an act of cold bloodedness. Perhaps all one can say regarding his attempt to soften this at the last moment, describing Anglo-Futurism as a “creditable project,” is that it is a testament to Mr Adams’s genialness. For I cannot recall the last time I read an act of such devastating critique committed in quite so polite a manner. Imagine stirring from the anaesthetic of an organ harvester to find he’s left you with enough money for a taxi home.

That said, Mr Adams is an equal opportunity critic, and has no qualms turning the scalpel on himself. In the essays on Traditionalism and Localism he criticises positions he held in his youth and even in earlier parts of the book. Much of these observations are judicious and, in the case of his reminiscences, quietly moving. All the same, I suspect for many an artist they may prove unsettling, particularly for those whose reverence for old masters has become calcified into a churning out of pastiche. As Mr Adams notes of Bruegel, “[he] only became great when he went beyond Bosch, when he broke free, when he formulated a new language to address different topics.” Throughout these essays the reader bears witness, as here, to the inevitable fissure opening between the tired conservative and the burgeoning reactionary, and it is in these pieces that Mr Adams makes the final cut. I commend all these to readers to seek out, along with his essay on criminality and the artist, which is a repost to the idea right-wing art should not, or could not, innovate by transgression. Further essays concerning the sculptures of such artists as Thomas J Price and the need to be alert to the intransigence of one’s liberal conditioning, show a healthy, steadfast, but generous approach to the question of what one is to do with the jettisoned liberal orthodoxy and its detritus.

Contrast the direct manner of approach here to the letters, and one can say the pleasure of the latter is in watching ideas and observations, often barely stated, cumulate over the course of many months and even years. Many of these are the seeds of stances Mr Adams will take in the later essays, but rarely is there a direct genealogy. Only by reading obliquely and through the gaps in his retrospective jaunts through Northern Europe and east coast America in his job as art critic, does one obtain a rendering of the subtle ways by which the tectonics of one worldview gradually give way to another. Whether or not this will appeal to every reader I do not know, but for my money these letters are among the most touching and enlightening aspects of the book. To read an artist keep in touch with his old tutors a quarter century after he left art school shows, even in this one-sided manner, the enduring relationships forged by the shared pursuit of fine art. Indeed, one grows to enjoy his regular missives describing to the likes of Basil Beattie, Roger Bates, and the art historian Simon Wilson the latest shows in Paris, Bruxelles, and New York. There are some brief gems too. In his correspondence with the late Brian Sewell, taken up in the years shortly before his death, we are made privy to a shared and healthy disdain for Da Vinci’s execrable application as a painter, as well as such delightfully apt and irreverent judgements as this of Rembrandt:

“I still think he is a weak colourist, certainly weaker than Giorgione, Titian and some later painters. He had the brain and eye of a draughtsman but the palette of a cook: oxtail, minestrone, brown bean…”

Observations such as this pepper the correspondences, and offer a flavour of the kind of conversational education one wishes still took place in the pub with one’s university tutors, delivered in hints to be followed, allusions to be ruminated upon. Mr Adams’s view of Magritte as an artist of chiefly Romantic temperament, and who I am given to understand was a formative influence, is just so illustrated here. Yet if there is one moment that stands out as a fulcrum in the personal development of Mr Adams, it is in this letter to the Australian artist Ryan Daffurn written in 2024:

“For many years I rejected the idea of writing about living artists, eschewing both praise & criticism, as I thought it was insufficiently distant to allow impartiality. But, what is impartiality other than a fear of weakness? Real artists living today need both praise and censure, if intelligent and articulate. I’ve needed it myself, so denying it to others is unfair. If I can help your art be known more widely, appreciated more deeply and valued more highly then it’s my duty—regardless of it also being a pleasure—to do my part.”

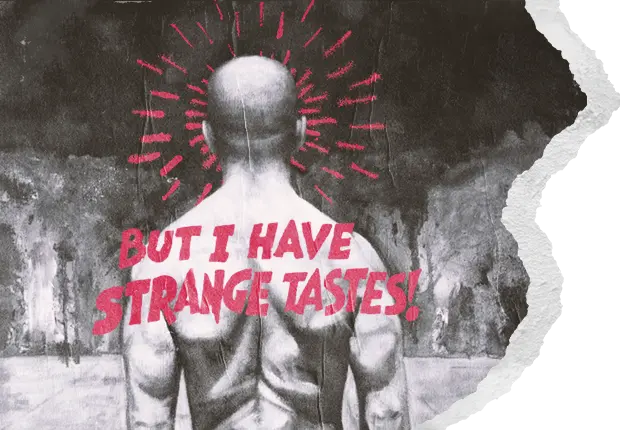

Gone here are the days of the isolated artist and critic, every bit as atomised—if differently—as the consumerist he distances himself from. Instead, there is an urgency, fuelled not so much by desperation but rather a note of quiet, even warm, confidence. Is it too far to say Mr Adams grew into himself? That is a question I shall leave each reader to decide. I shall merely point out the cover picture of this volume, painted in the early part of this year, which depicts a man, naked—shorn of what he once wore—and facing forwards into a nebulous hinterland of broad, energetic, even volcanic movement. That this hinterland has yet to be fully rendered should no doubt be taken as a statement of intent.

Looked on as a whole then, does it detract from the book’s worth that some of the essays in this volume have appeared elsewhere? Not really. For the curious effect of reading them bound together in the manner presented here is that each essay, speech, or letter begins to read not only as an argument, but as the kind of material a future historian, whether cultural or political, may just one day consult as source material. Of course, time alone will be the final arbiter of whether or not Mr Adams’s aims are to come to fruition, or whether the pieces in this volume shall be redolent of only a minor quirk in the annals of art history. Nevertheless, Imperium Press should be commended for publishing such a book. It goes some way to remind us that the pleasures of the Gutenberg mind are not relegated to matters of the past, but can aim to redress in some small way the unassimilable matter of the timeline. If there is a criticism to be made of its contents, it is that it describes the reactionary artist and his art primarily by means of the negative: he is not this, it is not that. Perhaps this is unfair, for if his positive renderings are diffuse it is only because, as Mr Adams makes abundantly clear, it is only by doing and the result of such doings, that the fruits of such an art can be understood. That he and a few like-minded artists are exhibiting in London this October should then be noted in any interested party’s calendar. For this book is really an exultation to the prevaricating artist to put himself to the task, to stop theorising, and—more to the point—to stop talking. In the end it stands as a rebuttal, at times both moving and considered, to Oscar Wilde’s famous line that “each man kills the thing he loves.” It is because of Mr Adams, and men like him, that for the finer arts of this country—and perhaps places further flung—there might just be some hope.

How to Start a Dissident Art Movement is available now from Imperium Press. You can purchase it here.