Write On!

Two years ago, I heard a sobering story about a young man who wanted to write.

He was a fresh out of college, working at a hardware store between a yoga studio and a Chinese takeout in a strip mall; he liked to pick the brains of a certain coworker, who happened to be a very literate crony of mine, on the latter’s cigarette breaks. During one of their confabs behind the building, Hardware Harry revealed to my informant that although he never cared for doing it in school, he’d begun to write in his spare time.

However, on his next breath, the budding author complained—as though it were an unavoidable snag in the creative process—that ChatGPT needed a lot of re-prompting to halfway approach what he had in mind and didn’t keep the story consistent as it progressed.

This young man’s situation strikes me as pitiable. The language of Melville, Mencken and McCarthy has been given to him as his mother tongue, which is a fat piece of luck for any writer; and yet, this zoomer has conceded, to a synthetic interloper, his birthright to sculpt with his own hands that able if refractory clay.

Plugging in prompt after prompt, he is not writing—he’s grinding a clicker game.

#

Every reptile in Silicon Valley from Altman to Zuck seems to be pushing his own “Generative Artificial Intelligence” model, or “GenAI” for short (or “GAI” for shorter, as in “fake and GAI,” if you will). Typically, this takes the form of an unwanted chatbot which our lizard overlords shoehorn into the latest versions of their stagnating or declining products, like Microsoft 365’s busybody, Copilot.

These latter-day brazen heads are not limited to “automatic writing.” Many chatbots—Grok, Copilot and ChatGPT to name a few—can be prompted to produce other media, sometimes including images, videos and audio; meanwhile, music generators, such as Suno or Udio, also write song lyrics and illustrate album art. This magical cross-functionality can make GenAI difficult to define, but every model essentially does the same thing.

The clearest, simplest and most all-inclusive definition of GenAI comes, in my opinion, from Jon Stokes, co-founder of Symbolic.ai and potential lizard. In his Substack article, “ChatGPT Explained,” Stokes writes, “a generative model is a function that can take a structured collection of symbols as input and produce a related structured collection of symbols as output.” Stokes gives letters in words, pixels in images and frames in videos as examples of the structured collections of symbols that these functions, GenAIs, suck in and spit out.

Now, a text prompt for “Bill Clinton playing the sax on stage in a blue dress” could produce an image with the likeness of Jeffrey Epstein somewhere in the audience. Accelerationists, brogrammers and other sedentaries might attribute this unbidden cameo to an intentional comic flourish on the part of the machine, but it’s better explained by relationships among the symbols within the model’s training data, which would likely include squillions of shitposts along the same lines; the connections between “Clinton,” “blue dress,” “Epstein” and “Epstein’s painting” were exhaustively preestablished by humans, not cunningly divined by a nascent consciousness.

GenAIs that primarily trade in text-based inputs and outputs are called “Large Language Models” (LLMs), referring to the amount and nature of the training data they require. I’ll touch on the ramifications of this shortly, but, first, it’s worth explaining what an LLM is and how it works.

An LLM is a mathematical function used to determine the next most likely word of a given text, whether at a full-stop or in the middle of a sentence. Under the hood, it identifies every input word with a lengthy series of numbers; these are coordinates that represent a word, its definitions and its relationships to other words. A single word can have as many as one thousand such coordinates, none of whose values are fixed. In fact, they’re readjusted, again and again, in parallel with those of an input’s other words to particularize and contextualize how the words are being used together. Having thus produced a numerical representation of the text, an LLM uses a probability distribution to finally pinpoint the next likely set of values, that is, the next likely word.

Practically speaking, a mathematical function makes no distinction between an incomplete document and a question—both are followed by blanks. To generate a response to a prompt, an LLM performs its basic function iteratively. First, it processes the user’s input and then adds a word; then it processes the original input and the extra word now as one text, and appends a further word; and so on and so forth, until it accumulates a sentence, a paragraph or a whole legislative bill. That this drudgery looks quick, fluid and easy is a sleight of hardware.

Existing texts by human writers are necessary to set the parameters for these operations. During its training phase, an LLM is incessantly quizzed on the missing last word of snippets from actual typescript. Its early gibberish answers are corrected, trillions of times over, which gradually hones its numerical representations to match words appropriately.

Although AI companies are famously cagey about the specs of their latest models, it’s commonly agreed that GPT-3, for example, was trained on forty-five terabytes of text data. When The New Yorker used GPT-4 to run the numbers, it claimed that’s roughly the word-count of ninety-nine million novels. AI companies scored this bag, of course, by scraping the internet—without a plan to inform, credit or remunerate any living authors or copyright holders.

Google Book Search established the precedent for this heist and made plenty of loot available for it too. In 2005, Google was fighting two lawsuits—one filed by the Author’s Guild and another by the American Association of Publishers—over its activities in big research libraries, scanning the books and uploading their contents to its searchable database without the consent of rightsholders.

Legal battles rolled on for years while Google (and others, like Amazon) continued to digitize and index print matter online. Finally, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals decided, in 2015, that Google’s unauthorized scans of copyright-protected works, uploads thereof into a search function and snippet views of same all fell under “fair use,” as being “transformative.”

Early on, Google had a vocal cheerleader in Kevin Kelly, “Senior Maverick” of Wired magazine. (To illustrate that publication’s spirit and impact, in ’97, Wired ran a piece called “The Long Boom: A History of the Future 1980-2020,” which was pivotal in persuading the investorati to regard the web as an instrument for infinite economic growth.) In 2006, The New York Times published Kelly’s manifesto, “Scan This Book!” Although Kelly is himself an author and his then publisher was a plaintiff against Google, he exalted “the moral imperative to scan” in order to “move books to their next stage of evolution.” Kelly foresaw a “universal library” which resembles today’s LLMs.

“Technology accelerates the migration of all we know into the universal form of digital bits,” Kelly preachified. “In a curious way, the universal library becomes one very, very, very large single text: the world’s only book,” much like the repository of cribbed prose swallowed whole by an LLM. “Each word in each book,” he envisioned, “is cross-linked, clustered, cited, extracted, indexed, analyzed, annotated, remixed, reassembled” in this new medium, which seems realized by LLMs. Writing is now the internet burping up and rechewing its own content.

Kelly wrote, without blushing, that search engine technology was “[p]ushing us rapidly toward an Eden of everything,” but not everybody was thrilled by his idea of paradise. Novelist John Updike (who wrote Rabbit, Run and The Witches of Eastwick) promptly responded in The New York Times to the manifesto, decrying the tech trends Kelly championed as “the end of authorship.”

Today’s AI companies, embroiled in their own legal battles, are angling for their products to be similarly defended as “transformative” of the datasets they’ve finagled. Meanwhile, anybody who’s solved a captcha to open their email or access a webpage has likely trained an AI without being paid. (By the way, if you wanted to know, “CAPTCHA” stands for “Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart.”)

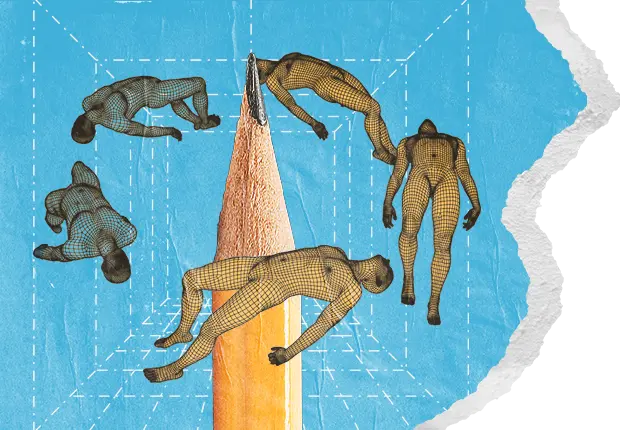

“Generative” is a misnomer, of course. If you’re hiding from whom you’ve plundered your data, you can pretend your AI was clever enough to make up the output by itself. In reality, GenAIs are just collage software with poor user controls which move around decontextualized bits rather than magazine clippings.

#

Sometime in the ’00s, while I was pursuing my bachelor’s in literature—and hoping to become a celebrated novelist—I shared a room on campus, in a gloomy dormitory made of conjoined towers, with a computer science major. He was always apprizing me of advancements in “machine learning,” a field that shook me up awfully.

I hoped he was overstating the progress being made. Writing, doodling and other fits of creativity with friends had gotten me through my very, very dismal teen years, and it distressed me to consider that my vocation, telling stories, could be mechanized. However, any web search for a milder second opinion dredged up spooky quotes by futurologists, like Ray Kurzweil, heralding “the Technological Singularity;” a point when computer power accelerates, on its own, beyond human control and understanding.

“The Singularity” was too inconceivable to me—outside the clichés of science fiction—to meaningfully prepare for, although it would interrupt my life in fifty, fifteen or even five years. To say the least, I was on edge.

My roommate also minored in jazz studies and enjoyed playing music over ancient beige speakers on his desk, plugged into his sleek laptop. Ordinarily, he preferred bebop and free jazz, which, to me, sounded like the gastric agonies of Pollock paintings, but one night he gave me a deliberate reprieve.

He had clips from three piano sonatas he wanted me to hear and challenged me to identify the composer featured in each sample. Listening closely, I gave my best guesses—Bach? Chopin? Mozart?—but he wouldn’t confirm these for me until he played through his selection. I didn’t mind; I actually enjoyed the music. Finally, my roommate divulged the ditties were from a new album, From Darkness, Light, by one Emily Howell.

Then he walloped me. Howell wasn’t a young savant with a gift for pastiche, he explained, but a computer program created by Professor David Cope of UC Santa Cruz, which had been trained on work by the composers whom I had just named. (How’s that for a Turing Test?) By way of reply, I doubled over in my UNICOR chair and burst into sobs of fat, scalding, heartbroken tears.

Try as he might, my roomie couldn’t calm me down. In that moment, the near future seemed to me a rancid dystopia in which the invincible math of determinism, as reified by the effectiveness of “creative” machines, would finally put the lie to human freedom and expression forever—and all I could do was watch as history ended before I hit twenty.

Apparently, another resident of the dormitory chafed at my unmanly grief as it reverberated through some very thin walls. Within the next day or two, the exterior door of my dorm tower was tagged by thick, black spray-paint, delivering a rebuke in large letters; “faggots cry.”

For context, that’s simply what we called “sensitive young men” back when I was one.

#

David Perrell is a youngish man, a writer, and a writing teacher; he’s also the host of the “How I Write” podcast. (In fact, he’s interviewed Kevin Kelly and Sam Altman on his show.) This February, across multiple social media platforms, he posted, “This AI boom has set off an existential crisis in me” to the point he shuttered his teaching business.

Perrell explained, “many of the skills I’ve developed and built my career on are becoming increasingly irrelevant” as a result, that is, of improving LLMs; “[t]he amount of expertise required to out-do an LLM is rising fast.” Based on this familiar forecast of technological progress, he has concluded, “the number of people who can gain an audience for their writing and outperform AI has fallen considerably — and will continue to do so.”

Perrell’s worries seem legitimate; low-hanging positions, like SEO stenciler, email drudge and blog padder, which were once vital springboards and stopgaps for creative writers, are being snapped up by software packages. As Mira Murati (formerly CTO of OpenAI and one-time product manager of Tesla) mumbled to students of Dartmouth College in 2024, “Some creative jobs maybe will go away, but maybe they shouldn’t have been there in the first place.”

LLMs are hard on seasoned writers, too. Not only are there many techniques, devices and tricks of the trade that, being formulaic, can be automated—for serial novelists, churnalists and other hacks exploit these gimmicks by rote—but GenAI, generally, targets any artist with a polished, hard-won, distinctive style, flexing its muscles by swift mimicry. (Think of OpenAI’s recent Ghibli filter.) Everything being on the web, innovators throughout arts and letters invariably feed the machines that later imitate them for the idle recreation of mediocrities.

With regards to his own career, Perrell said, “I’m investing more into personal audio and video,” but if what he claims about LLMs is true, and broadly applicable to all GenAIs, he’s setting himself up for another existential crisis when the computers move on to becoming podcasters.

Sousing the front row at a recent Davos event with his lisp, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei told The Wall Street Journal that AI systems will be “better than humans at almost everything” as early as 2027, causing total unemployment. It’s strange, then, that while the Trump Administration is deporting tens of dozens of illegals to save American jobs and wages, it’s also toying with investing $500 billion in AI infrastructure, a technology which, according to industry leaders, will bring about the end of jobs and wages. If there are no more paying jobs left on Earth, I guess all those kids Elon Musk wants us to have can slave away in gem mines on Mars.

Lately, the Tech Executive—as a species—is the economy’s apex predator, which status he’s happy to attribute to a sort of Digital Darwinism. Software has been, for him, a solid survival strategy; it has proliferated rapidly throughout different industries, first expediting, then assimilating, and now, with AI, automating all other fields of endeavor—and thus, subordinating them to whomever controls the software. (Ask any graphics artist you know about Autodesk.) This is what NetScape co-founder Marc Andreessen was gloating about when he wrote, “software is eating the world” in 2011.

However, before it could begin its feeding frenzy, software was first served the world on a silver platter by D.C. and Wall Street. The Tech Executive has oftener succeeded by the tried-and-true methods of flattering power, wooing investors and—see Bill Gates’s antitrust deposition—cheating competitors than by delivering a novel or functional product. (Or even a real one. Case in point, Elizabeth Holmes.) Let me add, tech execs would be nothing without the fawning press they enjoy from the media who are either too clueless about tech—Katie Couric was famously puzzled over what the @ symbol meant in the 90’s—or too complicit in its hype cycles.

Silicon Valley is enriching itself by burying us under layers of abstraction, not an “Eden of everything” but a “meta of everything.” Amazon, DoorDash, Steam and GenAIs demonstrate how Web 2.0 has become a series of platforms that absorb other activities, monetize them and algorithmically manipulate user engagement. Indeed, what Facebook is to our relationship with one another, LLMs are becoming to our relationship with words: the intrusion of a superfluous remove that reframes us as managers, rather than participants.

To a young man who wants to write, what LLMs promise him is guaranteed copy, rapid speed and limitless scalability; he will always have as much Lorem Ipsum as he wants, whenever he wants, to achieve untold heights of internet marketing. Needless to say, these are not the concerns of a diligent craftsman, or even an inspired amateur, who loves mucking around with words for his own pleasure, although he may hope to profit by it.

In a written culture, it is easy to forget that words are not merely blots for the eye to scan as fast as possible, but part of our very breath. As such, they carry within them wisdom about the world in which mankind has lived for generations.

For example, “branch” comes from the Latin for “paw,” which depicts trees as living things with vital members whose sacrifice for our shelter and warmth might be, in light of the etymology, better understood. “Cybernetics” comes from the same Greek root for “steersman” that also produced the word “government.” And “infant” literally means “one who is unable to speak.”

As LLMs rapaciously quantify them as statistical tokens of habitual use, in service of banal admen, chain-letter spammers and feckless influencers, words need passionate human writers now more than ever to rescue, revive and restore them to the organic riot of real life that is their source.

There’s one last etymology I’d like to share—for the word “desire.” The word “desire” comes from the Latin, desiderare, the root of which is “star” (sidus), which might come the phrase de sidere, or “from the stars;” as if to suggest that our desires—whether to write in the time of AI, to love that which we love, or to live on our own terms—are heaven-sent, God-given, cosmic in origin and purpose.

#

On the tail end of my undergraduate studies, a select group of my peers, a camarilla of tomorrow’s stuffed shirts, members of the honors program, organized a colloquium whose theme was, in the form of a question, “Are you ready for the future?” A lecture series with distinguished guest speakers was part of the deal. As a result, the science fiction writer Vernor Vinge—widely regarded as the foremost popularizer of “the Singularity”—came to my school for an evening.

Promos for the event, open to the public, announced a Q&A with Vinge to follow his spiel; and so, hoping that a fellow wordsmith, who had been chewing on the subject for decades, might supply me with better pointers than “faggots cry,” I worked up the pluck to attend. By contrast, a week or two prior to Vinge’s appearance, Kurzweil himself spoke on campus, but I was too afraid of that silicon scaremonger to go.

At the door to the venue—an auditorium of royal blue drapes and cushy retractable seats—honors students moonlighting as event staff, dressed in black, doled out notecards and pens to attendees for the Q&A. The card detailed two means of submitting a single question to Vinge. The first method was by writing it “on the lines below” and waiting for staffers to collect the card toward the conclusion of his prepared remarks; the second, by texting it “to the following number…”

This boded poorly for my planned interrogation; I had assumed curious parties would queue at a mic once Vinge was talked out, whereas ink seemed too one-shot to pin down my jumpy FUD.

Vinge spoke to a packed house—hundreds of people came out to see him—but none of his words left an impression on me, except, of course, when he blanked on the title of a “Victorian” must-read, which he praised for prophesying Skype and YouTube; and someone in the front row reminded him, E. M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” (1909). Continuing to overlook the essence of Forster’s message, Vinge tied the friendly reminder to the promises of cybernetic enhancement:

“You looked that up with your phone, right?” he observed. “See? Google makes us smarter!” (Vinge died in March 2024, shortly before Alphabet CEO, Sundar Pichai, inflicted AI overviews on all the search engine’s results, which told us to glue cheese to pizza and that it’s “totally normal” for roaches to live in human penises.)

I spent most of Vinge’s speech hunched over the notecard in my lap, struggling to write a sharper and sharper question with a duller and duller pencil, which I had bummed off the well-prepared Eagle Scout sitting next to me.

“What’s the point of honing a skill, like writing,” one of my efforts began, “when, in the near future, any semiliterate turd can push a button and produce works greater than Shakespeare’s?”

I erased that and tried again; “Why bother writing a novel painstakingly, with my own clumsy meat-hooks, when a competitor’s machine, rapidly simulating all possible iterations of a given theme, might chance upon my self-same idea and, within seconds, render it in a style that could take me years to master?”

But I nixed that also. Running out of time until the Q&A began, I finally decided on a simple question that would fit within the clean, readable area left on my ravaged card; “Are you a prophet of hope, or of despair?”

On present reflection, that was a naïve query to waste my card on. Lucky for me, however, the honors staffers broke their word to collect notecards from the audience. (And I had taken an aisle seat in order not to miss them.) The event was drawing to its close and, so far, Vinge’s attendant—yet another honors punk—had fed him only questions submitted by text message.

Perhaps those student leaders had sided with the cutting-edge of tech and chose to teach a lesson to any fuddy-duddies out there who insisted on handwriting. Go paperless, or go without!

What’s more, back in those days, I never carried my phone on me if I could help it; so, I asked the Eagle Scout if I mightn’t borrow his. Familiar with my troglodyte habits, he didn’t find the request suspicious. He was, in fact, my computer science roomie from years ago, whom I’d dragged along that night for moral support. Meanwhile, the whole notecard hiccup had given me a minute to change tack…

“Last question,” said Vinge’s attendant, flatly, before reading aloud my words; “What will posthuman literature be like?”

“That’s a fascinating question,” Vinge smiled. A glimmer of childlike wonder flashed across his bald head. After a short pause, he gave his answer, which began, “If you think about it, the first joke ever told didn’t have to be all that funny to get a laugh because it was the first of its kind.” And so, in summary, posthuman literature is that which won’t need to be any good because it will be new.

Vinge’s encomium of earthshattering, though frivolous novelty—no matter how it upends everyday life for generations to come—is the most boomerish pile of bullshit that I have ever heard.

By the way, when the website Big Think eventually grilled Kurzweil (a boomer) on how to prep for the Singularity the jumped-up showman’s advice was similarly glib: “Follow your passions.”

#

In February of this year, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella told podcaster Dwarkesh Patel that, despite their ubiquity, AI products aren’t generating market value yet. Tech journalist and the host of “Better Offline” Ed Zitron has estimated that OpenAI, which receives “cloud credits” and other bennies from its cozy relationship with Microsoft, lost $5 billion last year after revenue. Perhaps the writing is on the wall—Microsoft has lately reneged on its plans to build new data centers in the US and Europe. This comes on the heels of a deal the company made to reopen Three Mile Island to power their AI infrastructure. Well, now they can use it for reenactments.

On top of the staggering financial expense, GenAI has an environmental cost too. GenAI servers run blisteringly hot. (In fact, Sam Altman publicly remarked, on X, that the flood of Ghiblifications has melted some of GPT’s GPUs.) The hardware requires copious amounts of water to keep cool; according to The Washington Post, for a single 100-word output, ChatGPT’s hardware needs about 16 ounces of water, more than a whole bottle of Microplastic Springs.

Even so, the average Silicon Valley hoaxter can brush aside these and other glaring problems by promising his investors that, maybe, within the next 100 words it spews, the machine will propose its own fixes. The Singularity means never having to tell your shareholders you’re sorry.

Although they’re straining the limits of their imaginations, tech tycoons continue to propose flat, absurd futures which nobody wants. Sam Altman repeatedly claims, soon, a user will be able to simply prompt an LLM to “discover all of physics.” Zoom CEO Eric Yuan looks forward to a coming day when he can send a digital version of himself to online meetings, so he can go to the beach where, presumably, he’ll connect with everybody who also skipped the meeting.

In the meantime, there’s not enough high-quality, human-generated stuff left for GenAIs to chew up in order to improve their performance. A study published by EpochAI estimates that LLMs will run out of available text data by as early as 2026. Altman’s superbrain launched over two years ago; it’s eaten most of the web; and it still insists there are only two r’s in “strawberry.”

More data is not the magic ingredient for better computing. For twenty-plus years, Cycorp’s project, “Cyc,” pronounced “psych” as in “encyclopedia,” has been collecting a huge knowledge-base of millions of pieces of information—it’s been connected to Wikipedia since ’08—and it hasn’t yet sprung to life.

The simple rebuttal to the mythology of eternal recursive increase, of accelerationism, of the Singularity, and of all other varieties of pie-eyed techno-utopianism is a cursory glance at our present circumstances. Has Facebook streamlined human connection? Are microtransactions making video games more fun and immersive? How’s your HP printer these days, cost-effective and user-friendly? What degree in computer science does your mechanic need to work on your car? Has automating customer service made your gram’s returns to Walmart go more smoothly?

The hot trend in information technology might’ve been personalization, alas. Greater control over the functionality of apps, devices and platforms could still be given to the average user, whose tech-savviness the industry arrogantly underrates. After all, it was to boost the general public’s “computer literacy” that Apple and IBM donated thousands of PCs to schools in the ’80s; not to hook the pipsqueaks on their goods and engender a market of drooling gadget freaks…

Granted too much accessibility leaves systems vulnerable to amateur errors and targeted attacks; however, Big Tech’s obscurantisms and mystifications withhold agency from users, which leaves people vulnerable instead to manipulation and abuse by these systems. Ironically, one possible way to give nonexperts greater control over their devices and apps, and at low risk of errors or attacks, could spring from some of the same tools currently in development as “AI.” Smaller-scale language models, like DeepSeek, “made in China,” which can run on local hardware, could empower regular users. Such models could give guided tours of a device’s OS and, potentially, help users identify and disable surveillance features or other invasive, harmful doodads which publishers sneak into their products.

By contrast, the tech industry today applies AI to automate the parts of computers which users traditionally operate, like word processors, graphics editors and, soon, the power button.

It’s worth observing, too, that while OpenAI is crying foul that DeepSeek’s model has been trained on their data, OpenAI is also demanding that courts sanctify their consumption of copyright-protected material as “fair use.” In the words of journalist and science fiction writer Cory Doctorow: “Every pirate wants to be an admiral.”

Let us suppose, however, that GenAI was a cheap and sustainable technology; and furthermore, that people were paid for the data they’ve created and had control over its use, what Jaron Lanier—Microsoft’s Prime Unifying Scientist and author of You Are Not a Gadget—calls “data dignity.” Under those conditions, LLMs fit snugly among other writing tools that use existing print material, like found poetry or William S. Burroughs’s beloved cut-up technique. Similarly, there are artists who do interesting things with MidJourney and like programs. But rather than kooky playthings, GenAIs are marketed as viable replacements for human creators.

The remedy to AI saturation is not less technology, but more humanity. They’re usually depicted as isolated geniuses, romantic individuals, wanderers above the fog, but writers, artists and musicians constantly influence, collaborate with and steal from one another. Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst have had hands other than theirs produce many of their iconic works. Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman notably coauthored Good Omens together; and many bestselling authors benefit from contributors, too, whose names don’t make it to the front cover. Young men who want to write will do well to found (or find) salons, writer’s colonies and workshops where they can make connections with one another, encourage each other and pool their resources.

Above all, the important thing is to keep writing, putting words together for yourself, exercising your own ability to select them, feeling your way through one sentence after another. Writing does take time. (I thought I’d have this essay done in a week and a half; it took over two months.) But the process isn’t a problem to be solved so as to expedite the arrival of the finished product.

In fact, the process ought to be your focus. Writing better acquaints you with the shape of your own mind, be it a palace or a hovel. Writing teaches you how to think thoroughly and speak clearly—because nothing else is readable.

Finally, language belongs to man and mustn’t be forfeited to machines; we cannot allow Big Tech to infantilize us. An inarticulate public is easily snowed by the dazzling promises and specious philosophies of technocrats, politicians, journalists, businessmen and other fissilingual hoodwinkers.

With regards to finding an audience, it is true that the superflux of chatbot slop in book publishing threatens to drown out human voices. However, millions of books were published every year before GPT, Claude and Sudo came along; the odds are always stacked against a unique, emerging voice. But if you really are a writer, you will keep writing because you want to do it, and tenacity is the biggest marketing secret. It’s fortunate, too, that readers who aren’t scraping the web to feed a chatbot prefer texts written by flesh-and-blood authors anyway; Sports Illustrated ran AI-generated columns under fake names and reaped significant backlash.

I am willing to join the skeptics in saying that the AI bubble will pop. Thomson Reuters lately won a copyright suit against Ross Intelligence, an AI startup that trained its stochastic parrot on their published research and editorials. Crying into its transhumanist beer, Wired reported that the judge ruled in favor of the legal firm particularly because, “by developing a market substitute” to outcompete Thomson Reuters, Ross had violated fair use. I am hopeful similar rulings will follow, chastening GenAI’s current spree as plagiarism software.

As legal battles stagger on and LLMs hit the wall, we will continue to need human writers to tell our stories. Technologists, of course, won’t give up the struggle to replace their fellow men with kitchen appliances (which their Aspergic dispositions prefer); and yet, supposing Big Tech can roll out AGI, or that the Singularity does happen, we will also still need human writers to tell our stories.

So, to young men who want to write, it’s a win/win for you. Keep calm and write on.