Broken Open: Between War Bands and the Woke in Today’s Archaeology

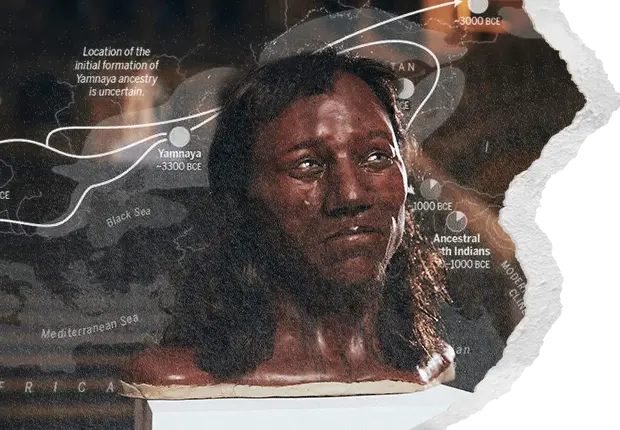

On February 7th, 2018, the general public in Britain were given the news that a piece of genetic analysis had been published about a Mesolithic man who lived in Cheddar Gorge some 9000 years ago. Ordinarily this might have been a quiet news story, one that yielded nods of interest and some chatter among nerdish corners of the internet. But this was a different kind of story – for front and centre of the reporting, in gleeful triumphal tones, came the new mantra, “our ancestors were black”. According to the geneticists, the Mesolithic man may have had dark-to-black skin and green or blue eyes, an image forever associated with the Western Hunter Gatherers, and now a piece of received truth within the emerging folklore of Britain’s multicultural past. Oceans of digital ink have now been spilled in opinion columns, social science journals and dissertations, each declaring with a smug satisfaction – “the British are racist”, “the British still have a problem with race” and “our black ancestors destroy the myths of white Britain”.

This isn’t a one-off or a rare event. Almost weekly now Western media outlets report archaeological finds which somehow tally perfectly with the morals of the day: transgender skeletons, female hunters, gay Palaeoliths, non-binary Vikings, shield maidens, black Romans, the list seems endless. So how exactly did we end up in a place where archaeology has been colonised by such politicised and obviously dubious results? What has happened to the discipline to end up with bizarre readings of gender politics being considered good osteology?

The Old Paradigm

The post-war years in archaeology saw a major change in direction in response to the emotional and intellectual fallout of the conflict, particularly among the ‘thinking’ classes, who pointed to nationalism and racism as driving forces behind the slaughter. Prior to the Second World War, archaeology had been developing along a trajectory which accepted the existence of defined ‘cultures’, identifiable through their particular type of material culture (pottery, buildings, weapons, art etc) and burial practices. This idea, that cultures could be readily observed through differences in their artefacts, had been slowly established since the mid-1700s and came to be called the ‘Culture-Historical’ model or approach. Culture-History was an explanation for how particular groups of people maintained a distinctive way of life and was strongly tied to the developing notion of an ethnic identity. Scandinavian, German and British thinkers had developed a distinction between ‘Kultur’ and civilisation, tying a ‘Volk’ to a unique pattern of behaviours, defined by Edward B. Tylor as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society”. Works such as Klemm’s General Culture-History of Humanity, a 10 part series published between 1843-52, expanded the idea and divided the world into the ‘active’ and ‘passive’ races, the pinnacle of each being the Germans on the one hand and the Negroids and Finns on the other.

Probably the most important figure of the time, however, was Gustaf Kossinna. Kossinna (1858-1931) was a Professor of Archaeology at the University of Berlin and pioneered a methodological approach to archaeology known today as ‘settlement archaeology’. He believed that Europe during prehistory was a jumble of different cultures, each with a distinct type of material culture. He argued that a culture was an equivalent expression of an ethnicity; therefore not only was Europe a pathwork of distinct cultural groups, but each group had a unique racial and ethnic origin which could be traced by following the material culture backwards and forwards in time. He postulated that the origins of the Indo-Europeans lay with a series of migrations which allowed a more creative and dominant culture to rise above the passive and weak. These ideas, more than any others, have been denounced today as pseudoscience, racist, bad scholarship and unworthy of consideration. We will return to them later in the essay to see Kossinna vindicated.

British archaeologist V. Gordon Childe took Kossinna’s ideas and developed a powerful and lasting methodological approach to prehistoric archaeology. In his 1925 works Dawn of European Civilisation and The Danube in Prehistory, Childe outlined a full and complete hypothesis of European prehistory, showing the distinct cultural groups based on their material culture and how various technologies had moved into Europe from the Middle East. This was a major breakthrough and many of the cultures have passed into the standard archaeological model, including the Bell Beakers and the Hallstatt. The triumph of the Culture-Historical approach can be seen today – it is still the dominant mode of analysis in most countries around the world. Its strengths lie in the ability for people and groups today to link themselves to past cultures and feel a sense of continuity with the past. It also allows nations to claim sections of prehistory and deliberately bind the current system to a previous and more ancient one, for good or ill. But it was precisely this quality which horrified the post-war generation of scholars and the backlash against Culture-History has ruled the academy ever since.

Rise of the New Paradigm

It wouldn’t be fair to label the rejection of Culture-History as merely squeamishness on the part of the post-war researchers. Decades of new ideas had begun to filter into the mix, including social anthropology, positivism, functionalism, ecological approaches and Marxism, to name a few. Archaeology found itself in a decade-by-decade intellectual maelstrom, as one idea competed with another and the scientific technology improved exponentially.

Out went older forms of study, including craniometry and philology, and in came radiocarbon dating, scientific objectivity and a massive influx of data from the natural sciences, including geology, biology, ecology, chemistry, experimental replication and palaeontology. The horizon of possibilities for a young researcher seemed limitless, with new methods of studying soil samples, dating artefacts and examining the molecular composition of deposits left on pottery and tools. Experimental archaeologists began building ships, siege engines, knapping flint and creating entire living villages to experiment with agricultural techniques and wooden architecture. Anthropology was integrated in new and exciting ways, and researchers like Marshall Sahlins, Colin Turnbull and Lewis Binford demonstrated that hunter-gatherers were not living in Hobbesian nightmares, but enjoyed rich and healthy lives, largely free of the toils of farming peoples. The 1966 ‘Man the Hunter’ symposium resulted in gender, firescaping and high-quality anthropological data being placed foremost in the literature. Marxism pushed economics to the front of many debates, allowing materialism to be taken seriously and the study of trade, coinage, markets and material consumption became dominant in every field from the Neolithic to the Roman Empire.

Many of these intellectual movements of course took place in a wider social context, as the Cultural Revolution of the 1960’s introduced feminism, identity, power and hierarchy, collective liberation struggles, subaltern studies, decolonisation and similar ideas into the academy. Evolutionary theories such as sociobiology and evolutionary psychology were also made use of by archaeologists and anthropologists – Napoleon Chagnon being a classic example.

However, within this brew of ideas and theories was a set of common commitments. The older intellectual traditions of Culture-History and forms of colonial and racial anthropology were denounced and largely expunged from the academy. Culture-History was an obvious candidate for ire, since many fascist thinkers and movements had made direct use of the approach, not to mention the sympathies within that generation of archaeologists for Nazism and similar ideologies. Kossinna himself was crucial in developing the idea of a biologically superior Aryan race and that the German nation was both the inheritor of this line. The Nazis founded the ‘Ahnenerbe’, an organisation dedicated to finding supporting evidence for the Aryan hypothesis. They launched expeditions to Syria, Tibet, the Antarctic, analysed runes in Scandinavia and searched for Atlantis.

Given this history, the post-war archaeological discipline purged its methodologies and approaches of anything which smacked of racialism and the search for ethnically distinct and superior cultures. As the decades moved on, archaeology built a shaky but tenacious fortress of intellectual defenses against part of its heritage, based on the total rejection of racial science. Part of this included the downplaying or dismissal of any theory which placed migration or invasion at the heart of its interpretation. It also involved promoting a form of fairly radical subjectivity which intended to demolish the idea of ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ stages of human life, to allow indigenous and hunter-gatherer people to be included in the human story without being denigrated to a lower level of existence. Altogether, by the 1990’s and early 2000’s, Western archaeology largely prided itself on having removed the majority of racial, nationalist, patriarchal and colonialist theory and rhetoric from within the discipline.

The Two Towers: the Woke and the Steppe

Into this comfortable consensus came two earth-shattering movements. These twin challenges were the rise of a hyper-militant Americanised obsession with identity and power, and the devastating return of the Culture-Historical model in 2015. The former is well known to everyone at this point and needs little explanation, but its particular manifestation within archaeology has been difficult and awkward and has yet to be fully digested. Some obvious examples include:

- The collaboration between historians and archaeologists to downplay and even deny the Saxon invasion of Britain, citing the colonial heritage of Saxon supremacy and the admission of a migration hypothesis.

- The ‘queering’ of Viking archaeology, the interpretation of Norse mythology as pro-LGBT, of burials as showing no common ancestry to Viking warriors, the existence of female fighters and non-binary or transgender individuals.

- The interpretation of several high profile Roman-era skeletons as sub-Saharan females.

- The insistence on gender parity during Palaeolithic and Mesolithic prehistory.

- The introduction of queer, disability and feminist theory within prehistoric archaeology as standard teaching practice.

- A commitment among archaeologists to ensure their work does not support or uphold ‘nativist’ or nationalist interpretations of history.

Taken together, a number of concerns have animated recent research, including the identity politics of race and sexuality, the older feminist insistence on equality and the anxiety of bolstering a multiracial narrative in the face of mass migration, starting in the mid-1990s. Alongside the rise of these issues has been the downplaying of more traditional topics, particularly anything focused on violence, invasions, migrations and conquest. A hybrid approach to prehistory has emerged which has largely maintained the older Culture-Histories, such as the Solutrean or the Maglemosian, but which focuses heavily on individuals, their particular lives, the lives of objects and the subjectivities of older ‘lifeways’. It’s noticeable how absent any large scale top-down narrative is for prehistory, often leaving students bewildered about how to contextualise historical processes and change.

However, the most grating part of these developments has actually been the destruction of theoretical tools in the face of the ‘woke’ approach. For example, the resurrection of craniometry to prove the ancestry of Roman skeletons, or the attempt to diagnose ‘gender identity’ from grave goods isn’t a comfortable outgrowth of archaeology as presented from the 1960’s onwards. It has the hallmarks of an imposed and outsider approach to archaeological interpretation, forcing researchers to twist older methods to suit new needs. Bioarchaeological studies of so-called ‘third’ or ‘fourth’ genders appeal to the ethnographic record for examples of men who behave as women and vice-versa, which do exist, but they then rely on diagnostic patterns on the bones of a person to reveal a contradiction between their livelihood and their sex. This is uncomfortable for a discipline which has worked tirelessly to abolish the presumption of gender roles and in other osteological examinations will attempt to subvert their own findings. For example, a female skeleton which shows wear patterns of upper limb extension that suggest throwing would be joyfully considered a female hunter; but on being forced to consider the existence of a ‘third’ gender, we might have to conclude that this was ‘actually’ a man who was born into the wrong body instead.

While these debates and intellectual currents have been steadily working their way into the legitimate side of academic archaeology, a more frightening spectre has emerged: the ghost of ‘Culture-History’ has come back with a vengeance. In 2015 two papers were published, Haatz et al 2015 and Allentoft et al 2015, both triumphantly holding up the severed head of post-war archaeology with the following conclusions: a third group of Europeans existed aside from the Western Hunter Gatherers and the Early European Farmers; these were either directly descended from the Yamnaya Steppe Cultures or a very similar group; and this group migrated into Europe from the Pontic-Caspian region and most likely began the spread of Indo-European languages. Along with these two papers came several more (Rasmussen et al 2015, Mathieson et al 2015 and Poznik et al 2015) which asserted that the Yamnaya invaders were fair skinned, much larger in stature and were predominantly male.

It is difficult to overstate the distress and anxiety these results caused in the archaeological world: a theoretical bomb had just vaporised the foundations of the entirety discipline of modern archaeology. Invasions were real, male warriors dominated Europe, they were white, huge and aggressive, they took local women and killed or subjugated the men, they had symbols of war – they were the nightmare Aryans of earlier generations. It was all real. Before the Haatz paper was even published several co-authors quit, distressed at the implications of their own research, the main authors had to write a 141 page appendix denouncing any connections between their findings and the Culture-Historical approach, but the cat was out of the bag.

In a 2017 paper entitled ‘Kossinna’s Smile’, Volker Heyd summarised several years of conference tears with the following: “While I have no doubt that both papers are essentially right, they do not reflect the complexity of the past. It is here that archaeology and archaeologists contributing to aDNA studies find their role; rather than simply handing over samples and advising on chronology, and instead of letting the geneticists determine the agenda and set the messages, we should teach them about complexity in past human actions and interactions”. Frustrations abounded across the global community – Ann Horsburgh, an African prehistorian railed bitterly: “such molecular chauvinism prevents meaningful engagement. It’s as though genetic data, because they’re generated by people in lab coats, have some sort of unalloyed truth about the Universe.” But the bombs kept going off. In 2018 a paper by Olalde et al broke the news that up to 90% of Britain’s Neolithic population were replaced by incoming Bell Beaker steppe migrants. It could not have been more devastating for the old guard, many of whom have spent their lives dedicated to a particular theory of Beaker pottery movement, summed up in the famous ‘first lecture’ phrase – “pots are pots, not people”. The return of Kossinna and his ‘settlement archaeology’ has been quickly dismissed as ‘Risk Board archaeology’, but despite the pleas, walk outs and demands of researchers, Kossinna is indeed smiling.

The Gathering Storm

Sharp-eyed readers will have noted among the reactions to the 2015 papers this revealing phrase – “we should teach them about complexity in past human actions and interactions”, referring to archaeologists teaching geneticists about complexity. Or in other words, we don’t like the results you’re proving, we need to teach you how to produce better ones. This threat is likely the opening salvo in a new war to reclaim the narrative from the scientists and bring it back into the text house of traditional archaeology.

This conflict between genetics and older methods of interpretation is in its infancy. The first ancient skeleton to have his genome fully sequenced was a Greenlander in 2010 by Eske Willerslev. Clearly, we have many years ahead of us. A good indicator of the emerging struggle is in the 2019 paper ‘Present Pasts in the Archaeology of Genetics’ by Frieman and Hofmann. In it, the authors rail against the Yamnaya steppe war band interpretation of the 2015 papers. They build a laughably absurd case that the media had racialised the Yamnaya, by decrying the use of the term ‘thugs’ as racist in North American parlance (the paper was published in Denmark) and complaining about an Armenian translation of the Indo-European war band tradition as ‘Black Youth’. They demand that genetic information such as eye colour and skin tone not be reported in the literature, state that home and hobby DNA testing kits have fuelled an obsession with appearance and make the bizarre claim that the fact that dominant males reproduced more in prehistory should be irrelevant in genetic reporting. They state: “It is time to question whether the almost exclusive emphasis in our narratives of the past on successful, conquering, increasingly whiter and male individuals, the classic winners of (pre)history, is terribly well thought out, or indeed an objective representation”.

But the real meat of their pitch comes at the end, where they make a series of further demands that archaeogenetics submit to the greater interpretive power of traditional archaeology. Hiring non-geneticists to write lengthy and complex additions to papers, altering publication standards, educating university press officers and so on – the fight is now on. In a similarly hysterical paper Hakenbeck (2019) increases the pressure on the geneticists and looks even to pull down the commercial DNA testing companies, stating that white nationalists are taking to online forums to compare ancestry results, looking for Y-chromosome haplotypes which might identify them as Yamnaya. We should expect to see further and more institutional changes in archaeology to ensure that the results of these genetics studies are dampened and problematised. They won’t be able to ban these studies entirely – almost all the money in archaeology now goes into such STEM-oriented work – but they can and will double down on making the results as muddied as possible.

Conclusions

Archaeology has come full circle from the late 19th century to the early 21st. The older thinkers who looked to the material artefacts from excavations and carefully categorised them by type and age have been lifted from their obscurity and deserve wider recognition. Only with the absolute precision of genetics have their names and ideas been reinvigorate. A more interesting future for archaeology lies ahead, one where migrations, conquests and vitality are back on the table. To be a traditionally liberal academic working on archaeology today is to be hemmed in between the ghosts of Culture-History and blue-haired students demanding that skeletons be considered queer third genders. The latter has the institutional backing, but little public support and almost no research outputs. The former is ploughing ahead into new territory and leaving behind the old guard with their beaker pots in their trembling hands. A real fight has smashed the consensus, and the potential direction of archaeology is now up for grabs in a meaningful way. If more geneticists, interested in Culture-History and looking to determine the truth of the Indo-European and other great migrations, were to be trained and enter the profession, we could see a powerful new direction in scholarship. Of course, this enthusiasm should be tempered by the realities of working in a captured and hostile institution, but for the first time in decades there is a breach in the walls and we should take full advantage of it.