Hockey Was the Last Masculine Team Sport

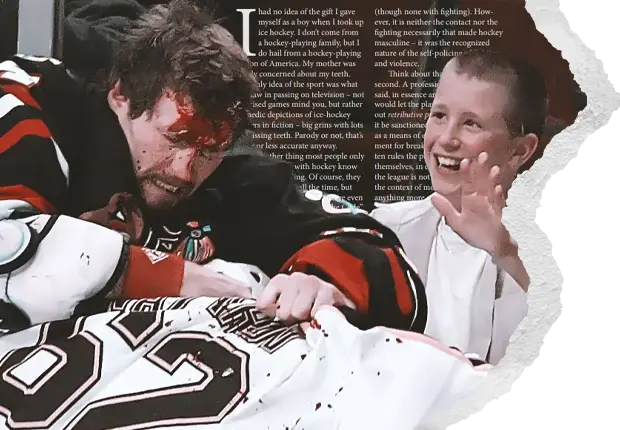

I had no idea of the gift I gave myself as a boy when I took up ice hockey. I don’t come from a hockey-playing family, but I do hail from a hockey-playing region of America. My mother was overly concerned about my teeth. Her only idea of the sport was what she saw in passing on television – not televised games mind you, but rather comedic depictions of ice-hockey players in fiction – big grins with lots of missing teeth. Parody or not, that’s more or less accurate anyway.

The other thing most people only casually familiar with hockey know about is the fighting. Of course, they think it’s all fights all the time, but there is a nuance to it. There are even unwritten rules known as “the Code” that govern it. It is this element that made hockey the last masculine team sport.

There are still masculine individual sports, some such as MMA which are nothing but fighting. There are other full contact team sports (though none with fighting). However, it is neither the contact nor the fighting necessarily that made hockey masculine – it was the recognized nature of the self-policing of fighting and violence.

Think about that for just a second. A professional sports league said, in essence and reality, that they would let the players themselves dole out retributive pure violence and let it be sanctioned within the game, as a means of extra-judicial punishment for breaking informal, unwritten rules the players come up with themselves, in effect admitting that the league is not in control. Within the context of modern sport, is there anything more masculine than that?

I specify “league” here as fighting in hockey is not universal, as many outsiders would think. It is and has pretty much always been limited to hockey specifically in North America – the Europeans never really had it in their game, and whenever it did happen, they didn’t know how to handle it. The most famous example is probably the 1987 World Junior Championship game between Canada and the USSR. The game ended with a nearly 20 minute long bench-clearing brawl between the two teams. The European referees and other game officials had no idea what to do. They actually left the ice and attempted to get the brawl to stop by – and I’m not making this up – turning the lights in the arena on and off like you would with an unruly kindergarten class. The Soviet players didn’t really know how to handle it either, fighting back very awkwardly initially, and eventually more or less passively accepting their physical beating by a bunch of rowdy Canadian teenagers. Though less extreme, that is the format for nearly every very physical game between North American and European teams, before and since.

What I’m about to say is applicable only to professional hockey, and only in North America. Don’t go doing anything at all like this in your local men’s recreational league. Furthermore, nothing I say here is gospel. The Code is informal. What I am writing here is simply my interpretation of it, and a brief one at that, only covering the most common situations.

So what is the Code? What can and can’t you do? What will earn you a beating? Well, one particularly interesting part of the Code is that committing a penalty, any penalty, no matter how large or small, that the referees do not call, will likely result in violence. A bit of an oddity in that since you can’t beat up a referee for missing a call, now someone on the offending team needs to pay the price for it, not directly through any fault of their own, but rather the fault of the referee. This has less to do with deterring the other team from committing penalties, but rather to get the message across to the game officials that the game is getting away from them, and they better shape up and not miss any more calls.

The Code carries over into other games. Teams have long memories. Just because incidents happened in one game doesn’t mean everything is back to zero for the next game. One of the more well-known long-term grudges stemming from the Code was the Avalanche/Red Wings rivalry. In a playoff game in 1996, Avalanche player Claude Lemieux broke Red Wings’ player Kris Draper’s face and knocked out five of his teeth by hitting him from behind and into the boards in front of the bench. This hit resulted in a feud between the two teams that lasted for the next seven years, and aside from the many fights, included not one but two line brawls (including goalies!) in that span of time – line brawls being a rarity since the 80s.

One of the more nuanced portions of the Code governs actions taken against star players. Generally, they are above retribution, but if and only if they do not abuse this status afforded to them. Obviously things like taking cheap shots is a violation of this, but interestingly, so is acting like you’re untouchable. Hockey is a gentleman’s game, so much so that it might be the only sport that has evolved an enforced ego check mechanism. Don’t believe me? The Code also protects smaller players, or players who don’t normally fight, stars or not. You can’t beat up the small guy or a guy who isn’t known for fighting, unless he himself is picking the fight with you, or he has done something dirty. Similarly, goalies are protected as well. While there have been instances of goalie versus player fights, they are rare, and almost always picked by the goalie. Goalies may fight other goalies and be within the dictates of the Code, but such fights are still rare nonetheless, given the physical distance goalies are from each other on the ice, and that crossing the center ice line by a goalie is an actual penalty in the official rule book.

Okay, so let’s assume you’ve got the ideal situation: a big guy who is known for fighting takes a cheap shot at one of your star players. Can you fight him? Well, you still have to be polite about it and ask first. Yes, you’re about to have a bare knuckle fistfight, but you have to agree to it. Gentleman’s game, remember? You don’t have to verbally agree, though that’s quite common, but the knowing nod or the more obvious dropping of gloves counts as agreement. Curiously though, strict interpretation of The Code mandates that if your opponent declines the fight in this situation, you are in the right to fight him then and there anyway. The one exception is if your opponent agrees to fight at a later point. It’s not uncommon at all for a player to say something like “Yes, but on the next face-off” or some other designated point later in the game to have the fight. Declining the fight is cowardly, but delaying it to a predetermined point is not.

It’s also a misconception that fighting is out of hatred or an attempt to injure your opponent. For example, it’s against the Code to accept a fight and then curl up into a ball on the ice and protect yourself, but it’s also against the Code to keep hitting a player who does this. It’s also against the Code to keep hitting a player when he is down if he legitimately falls over during the course of the fight – once one guy is down, the fight is over. The intent is not to injure. Above all, it is a means of policing behavior, deterring cowardice, and showing mercy, in the most violent and direct way acceptable to a contemporary viewing audience.

This concept even extends to line brawls (fights where everyone on the ice, usually except the goalies, is in a fight) and bench-clearing brawls (self-explanatory). Such situations are strictly one-on-one, and it is preferable, if possible, for you to match up with someone your own size, and for the stars or other infrequent fighters to pair off and fight each other. If all of what I have described regarding the Code sounds very white to you, you’re partially correct. It’s very Canadian. Which until very recently meant white. It will be interesting to see if this honor and sportsmanship persists. I don’t have high hopes.

There are of course other, more traditionally recognized displays of masculinity in hockey. Hockey players are well known for their propensity to continue playing through what would be considered severe injuries; fractured legs, hands, arms, ribs, broken or knocked-out teeth, broken noses, or stitches received to the face during a line change right on the bench by one of the team’s trainers. We are also well known for our desire to not protect ourselves with gear. The last helmetless player, grandfathered in after the league mandated helmets in 1979, was Craig MacTavish, who played without one until he retired in 1997. Curiously, I do not recall him ever having had a head injury. Glimpses of a past masculinity can even be seen in the official NHL rules. For example, a high-sticking that does not draw blood is only a two-minute minor penalty. A high-sticking that does draw blood is a four-minute double minor. A high-sticking that sufficiently injures another player is a five-minute major. All at the discretion of the referee, of course, but it is interesting to note that the rule does make a distinction between whether or not you made another man bleed.

I say a “past masculinity” and that hockey “was” the last masculine team sport. What happened? Well, in short, the NHL was in many ways a parallel to what happened to NASCAR – both sports in the 90s attempted to court the mythical “casual fan.” What is a “casual fan”? My own interpretation would be as follows: a shit-for-brains American who watches ESPN’s SportsCenter at least four hours a day and is so sportsball-cucked he’s maybe three or four leading questions away from admitting he’d let an entire basketball or football team run a train on his wife or girlfriend if it meant they win the BIG GAYME. Imagine ruining something to the point of alienating your followers to appease people who don’t like it in the first place and never will. That something only Christian denominations are supposed to do, not sports! I guess I’m kidding, but not much. There is also a parallel to what happened to the churches in Canada, both Catholic and Protestant.

The first big change was the institution of the “Instigator Rule” in 1992. The rule stated that whoever started a fight would be assessed a minor penalty on top of the fighting major. Over the course of the 90s, this resulted in the creation of a player archetype known as pests. Pests are players that operate in the gray areas of the rules, who don’t officially break any rules, but will bend them as much as possible, for the sole purpose of getting a player on the other team to actually break the rules, and then acting like they are the victim. It’s not hard to see why they’re disliked. Pests are often low-talent players, who poke, prod, hit, shove, talk trash, smugly smirk, clutch, grab, and trip other players, right up to the point of drawing a penalty but stopping just short, and hoping to abuse this tactic to the point of getting someone to “instigate” a fight against them. Further crackdowns on fighting over the course of the 90s to appeal to those “casual fans” and “for safety” made the situation even worse.

The biggest problem though was Gary Bettman. Bettman is a former NBA executive who was appointed commissioner of the NHL in 1993 despite knowing nothing at all about hockey. He can’t even skate. His tenure has seen the league’s expansion to markets it should not exist in – namely the American South and Southwest. He moved teams out of Canada, he moved teams out of parts of America that actually have ice in the winter, and moved them to deserts and subtropical parts of the country. This expansion has resulted in a sharp drop in goals per game, as there are not enough skilled players to staff all the teams and maintain that level of scoring. He has overseen rule changes that spit in the face of the traditions of the game, all in pursuit of that mythical “casual fan” out there that was going to fill arenas and get the league some big television contracts, and of course the increasing calls for “safety” from a feminizing and de-Westernizing Canada. Gone are the days where you could even have blood on your jersey. None of these tactics worked, and the league is a mess, and he gets booed every season when he presents the Stanley Cup to the winning team. He probably gets off on the boos.

This is all at the professional level, of course. There is something entirely different going on at the grassroots level though. A lot of us of our philosophical persuasion wish there was a place where we could be ourselves and openly so. Gyms are one such place. They are right-wing cultural spaces. In my experience, gyms have nothing on hockey locker rooms, at least in America. I can’t speak for Canada, and given the ubiquity of hockey up there, it is likely different, but as far as Americans go, I dare say there is no more hardcore right-wing demographic than hockey players.

People mistakenly think that this “new right” thing is the same old stupid trope of the “dumb redneck” or whatever caricature exists in the minds of people whose mental development ceased at some point in the second Bush Jr. term. No, the new right, the dissident right, whatever you want to call it is a North/Northeast, urban, post-industrial hellscape phenomenon. People who have lived and seen what globalization does to places. Exactly the same places where hockey is popular – the Northeast and the Great Lakes region.

Your average hockey locker room is full of young men from these places, are proud, aggressive, fit, and simultaneously violently anti-socialist yet Russophilic. To put it into perspective for you, the gyms around me were some of the first places to lift mask requirements. Even then, I would still see a few people in there with them on, and the employees were still required to wear them. The rink? Never a mask in sight, even among the employees. This is a right-wing space, and not in the strictly “normie” or “MAGA” way, though they are Trump voters. If this thing of ours is to grow, it needs to grow on all fronts. It may have started in the gyms and on the internet, and it is growing into visual art, literature, and any and all other spaces it can. What I am saying here is to consider the space that is grassroots hockey in America, and what that can be for us too.