The Departed Modern Man

By my count, Martin Scorsese has directed six films explicitly about being a gangster. If we relax the criteria to films that simply deal with the seduction of inflicting violence, of easy money and of beautiful women, then the count is far higher. This makes sense for Scorsese artistically — after all, he spent his childhood fairly sickly, and in a house that didn’t read. Instead, he sat at the window in Little Italy and watched the neighborhood. To pull a quote from Roger Ebert, “In the 23 years I have known him, we have never had a conversation that did not touch at some point on that central image in his vision of himself — of the kid in the window, watching the neighborhood gangsters.” As happens to many in life, we become extensions of the children we once were. The boy watching gangsters at the window became the man watching them on the monitor as he directs.

Marty is endlessly fascinated by these men, who band together and are free in ways that you and I are not — Goodfellas, of course, directly plays out his childhood fantasy. Yet of all his gangster films, there is one that is a purer distillation of his own central artistic tension. I speak, of course, of The Departed.

The main character of the film is Matt Damon’s Collin Sullivan, and the first real scene is him as a child, encountering Jack Nicholson’s Frank Costello, Boston gangster extraordinaire. Colin is watching Frank shake down a store owner, when Frank sees young Colin watching him. He orders the owner to package up some bread and milk (and a comic book), giving it to Colin to take home. An easy reading of this scene is that it’s the first time Colin is being paid off to look the other way — which will turn out to be the formative moment in his life. However, it’s what immediately follows that makes The Departed such a load-bearing study of masculinity of the 21st century: Colin is seduced by the gangster way of life and doesn’t become a gangster. He becomes a cop.

The importance of this is difficult to overstate. If we look at Colin’s formative moment more closely, the true picture comes into focus. The camera follows the store owner grabbing a loaf of bread, holding two cartons of milk. Frank throws a comic book on top as Colin hefts the newly filled bag. Is this what a twelve year old kid would get bribed with? Common groceries?

No. What’s happening here is Colin himself is, for the first time, adopting the desires of another. Frank decides what to fill the bag with, and Colin trundles off, clutching it. This is because Colin is unique in that he has no idea how to desire. Instead, he instantly adopts the perceived desires of those around him. It’s this quality that makes him the perfect embodiment of modern masculinity. It’s also what makes him the perfect mole.

To fully understand the connection this trait has to modern masculinity, we have to take a look at an enigmatic book entitled, Sadly, Porn, by Edward Teach. In this oblique and purposely obtuse book, Teach proposes that modernity is marked by a universal inability to genuinely desire. In an ideal world, you would desire something, fantasize about getting it, act on those fantasies, and then either succeed or fail in getting it. This is how Alexander the Great functioned, sleeping with a sword under his pillow and a copy of the Iliad by his bed. He fantasized about conquering the known world, and then acted on those fantasies. This is not how you or I function.

We don’t function this way because we are incapable of real action, because we are incapable of even desiring in the first place. Instead we are bombarded with algorithms, advertising and social media that tell us what (and how) to desire. And it is hardly restricted to shopping. Teach uses the example of finally bedding the hot sorority girl. It’s never quite as satisfying as you think it will be. Once you sleep with her, she becomes a real person: “just an econ major.” Worse, she is still a hot sorority girl to everyone else, but to you she is just an econ major. As Young Werther [@werther_n] astutely observes on his Substack, instead of banging a girl you “matched” with on Tinder (i.e. were passively matched with), “Has it ever occurred to you to ask out a girl you actually like?”

This is Colin. His capacity to absorb the desires of those around him is nearly limitless, and can be seen even in the smallest encounters. An early one is when he rents a spacious apartment overlooking Beacon Hill. The realtor makes a number of insinuations regarding his financial situation. What’s interesting is he doesn’t appear troubled by the questions until he gets asked if he’s married. “I have a cosigner,” he fires back with a glare. The easy reading of this scene is that the realtor is insinuating that Colin can’t afford the apartment as a police detective. The popular reading is that Colin is gay, so it’s the question of marriage that sets him off. But these miss the truth of his character: that he resents being questioned about what he actually wants. “I have a cosigner,” can be understood as the ultimate justification to Colin: “Someone else wants this too”. Colin couldn’t get an apartment without a cosigner. He wouldn’t even have the desire.

As tuned in to others’ desires as Colin is, perhaps Colin is simply content to absorb and project these things himself? More directly, how do we know that Colin himself doesn’t desire what he says he does? Because like the best liars, Colin is best at lying to himself. And he is so good, he may have convinced himself, but his body keeps the score. His body betrays him.

Colin’s romantic pursuit of female psychiatrist Madolyn (Vera Farmiga) is crucial because it illustrates this defining quality of his in fine detail. On an early, expensive dinner date, Madolyn challenges Colin.

Madolyn: “You know what Freud said about the Irish?”

Colin: “Yes I do.”

Madolyn: “If you actually do I’ll see you again.”

Colin: “Who says I want to see you again?”

Madolyn, worried, pauses. “Don’t you?”

Off her worried expression, Colin laughs. “You should see your face. Of course I want to see you again.” Colin had to see that she wanted him before he could admit to wanting her. Once he’s confirmed what she desires, then he’s safe to project it back to her: of course he wants to see her again. If she didn’t, then he would effortlessly switch — well I didn’t like you anyway. He can’t make the decision for himself and say the truth: yes, regardless of your feelings, I want you.

While his strategy works in the short term, it fails in the immediate and long term. He’s unable to perform sexually, even though Madolyn has everything he should need to “work overtime” as he enthusiastically lies to Alec Baldwin about his relationship. But he just wants to be the kind of guy that can get a kind of girl like her. He doesn’t like her. Colin is the dog who caught the car. In fact, the happiest he seems around her is when she asks if he wants a “French donut”, offering him another desire of hers that he can adopt.

The common reading of these scenes is that Colin is gay, and closeted so deeply he can’t even admit it to himself. The film was released in 2006, and the push for nationwide gay marriage was in full swing. Colin’s (very liberal) original sin: not acknowledging his homosexuality. And yet, Scorsese directly refutes this at the end of the film.

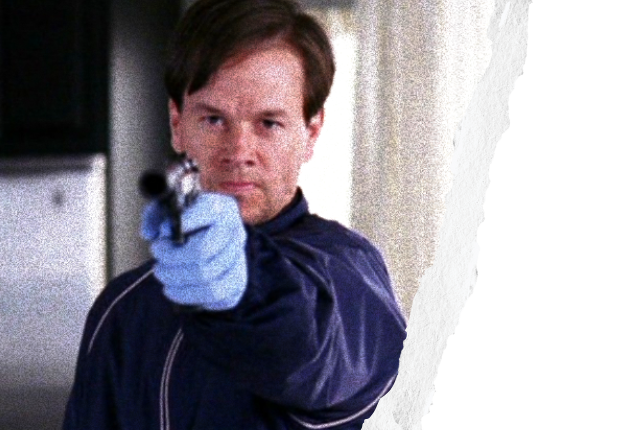

In the final scene, Colin returns home with a bag of groceries. Everyone involved in the extensive mole-hunt is dead or gone. Returning to his apartment he opens the door to find Mark Wahlberg’s Dignam waiting for him. Dignam has spent the entire film angry, slinging obscenities and insults at every single person who crosses his path. Here though he is calm. Saying nothing, he shoots Colin in the head.

The groceries spill out across the apartment like brains, revealing bread, cartons of milk, and “French donuts”. Even here, at the end, Colin is still carrying around a sack of other people’s desires. In contrast is Dignam, saying nothing and at last not filled with rage. Pure action.

Scorsese, the boy watching the gangsters, didn’t become a gangster — he became a professional voyeur of them. Colin is seduced by a gangster and instead becomes a cop. This is how desire works for the modern man, unable and unwilling to fantasize and act on those fantasies, he instead absorbs the fantasies of those around him, all the while wondering why, why he is so incapable of meaningful action. Estranged from himself. Departed.