Why You Should Read Jacques Ellul

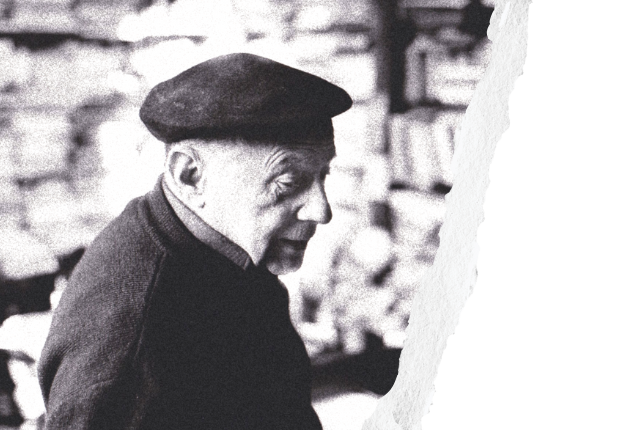

One of the aspects of the dissident right that I find the most compelling is the intellectual ferment. There is a genuine desire to understand our moment. How did we let things get so bad? When did we go off track? What were the causes? Politics? Religion? Race? Sex? Diet? — Architecture? There is a real desire to understand how things really work. One author that should be on everyone’s “must read” list, in this regard, is French sociologist, philosopher and theologian Jacques Ellul.

Ellul has written widely on numerous subjects but is best known for his work on technology and propaganda. He can be challenging in that he tends to examine every subject he looks at exhaustively, with an unflinching willingness to see the hard realities of the way things are, refusing to let people off the hook, not allowing easy justifications. But if you want to understand the way thing are and why they work the way they do at the deepest levels — the source code of modern life, so to speak — there is no better author than Jacques Ellul to help with that. His works should be considered an essential part of the dissident-right canon.

Let me very briefly walk you through a few key books, giving a brief introduction to each.

The Technological Society

What makes this book particularly helpful in understanding our current moment is that Ellul takes the time to develop a history of technology, examining the process of how we shifted from the long period in which people used tools and were their master, to today’s situation where we are now subservient to a vast technical system. He gets past merely looking at the technology itself, to help readers understand that the most important thing about technology is not the devices and machines themselves, but instead a way of thinking that he calls “technique.” It is this technical pattern of thought that has become all-encompassing in our society. All problems today are seen as technical, and all solutions are a form of technique.

The Technological Bluff

Ellul’s mature work on the subject of technique. For me, this was the first book of his I read. In it, Ellul develops his thesis regarding the “ambivalence” of technology. People generally think about technology and technical thinking, a.k.a technique, in one of three ways: good, bad or neutral. The first two are obvious. The third is more prevalent, and more dangerous, he argues. The view that technology is neutral tries to make the argument that what is important is how you use the technology. If you use it for good ends, its good. If you use it for bad ends, it’s bad. This understanding, argues Ellul, entirely misses the point of technology. It is especially dangerous when analysing a large technical system like the administrative state. Most of us see it as an empty vessel that we then fill with political content. This is mistaken.

All technology has its own inherent telos. The mere implementation of techniques will have good effects and bad effects. Both come together. The benefits are often frontloaded, thus making it easy to sell new innovations and new systems. The problems are often unforeseen and show up later, once many of the benefits have been realized. This then encourages a new round of technical solutions to be implemented to solve the ills of other technologies. Thus, the whole technical system grows ever more complex and fragile while the problems become more entrenched and difficult to solve, if at all. It is like a Ponzi scheme. The one thing we cannot do is to say, “no,” as this would challenge the whole ideology of Human Progress. So, we proceed always “forward.” Ellul calls this the “unreason” of the technical system.

Understanding the “ambivalent” nature of technical systems like the grand complex of the administrative state in all its forms in government, business, NGOs, and non-profits, impresses upon us that it is not possible to simply take control of the administrative state and wield it for conservative ends. The whole technocratic system was built by liberalism, for liberalism. The very nature of the system is an attack on traditional, conservative ways of being and doing things.

Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes

The left nature of the technological system is brought more clearly into focus as Ellul focuses his attention on propaganda. We tend to think of it like brainwashing, but its purpose is not really to change how we think, although it does do that. Its primary function is first of all to change your actions, to get you to serve the propagandist. Once your actions are aligned, your thoughts will follow to justify them, even if all you do is feel what they want you to feel. Because technological society is not natural, but is instead the artificial imposition of rationalized systems, the primary purpose of propaganda is to adapt people to live within the modern technical reality built around the utopian left ideal of Human Progress.

Your thoughts are not your own. You are not free. You have been, since birth, propagandized to fit within and serve the grand technical system. You are the product of propaganda. A series of fundamental myths support an entre edifice of smaller myths that determine every aspect of our existence:

“In our society the two great fundamental myths on which all the other myths rest are Science and History [that is, Progress]. And based on them are the collective myths that are [technical] man’s principal orientations: the myth of Work, the myth of Happiness (which is not the presumption of happiness), the myth of the Nation, the myth of Youth, the myth of the Hero.”

Propaganda reinforces the technical system built around these core myths. Anything which tries to counter-message the main mythic structure of our society, such as an actual conservatism emphasizing austerity, sacrifice, discipline and limits will find little purchase in society. This is why most who call themselves conservatives are actually just cautious liberals. It’s why they never actually oppose the system:

“[because of the myth of Progress, propaganda] must be associated with all economic, administrative, political, and educational development… thus… the general trend toward socialization can neither be questioned nor overridden. The political left is respectable; the Right has to justify itself before the ideology of the Left (in which the Rightists participate). All propaganda must contain and evoke the principal elements of the ideology of the Left in order to be successful.”

The Political Illusion

In this book, Ellul specifically looks at many of the common ways that we understand our western democratic systems and exposes them, one by one, as illusory. He begins by attacking the discursive presentation of our modern political system, arguing that all states are founded and maintained by violence. One of the key tenets of liberalism is the assertion that society can be run and founded by reason and discussion without recourse to violence. This is Clausewitz’s dictum that war is what results when discussion and negotiation break down, “War is politics by other means.” Ellul, and other authors like Carl Schmitt, argue that the opposite is true, that all societies are founded and maintained by violence. Liberalism, by means of propaganda (which is itself a form of psychological and spiritual violence) attempts to hide this reality from us.

Ellul attacks the notion that the administrative state can actually be reformed. Once you understand its technical nature — that technique is not neutral — that the administrative state is at its heart an expression of the system of liberalism, that the system has its own ideological content, it becomes more obvious that meaningful reform is not possible. Additionally, reform would require you to become expert technical administrators, thus absorbing you into the system and expanding it. If you do succeed in reforming it, you only make the system stronger and more robust.

Autopsy of Revolution

Having realized all of this, you’re ready to receive Ellul’s message in Autopsy of Revolution. Here he goes back to the beginning of the revolutionary period to examine the French and American Revolutions. He demonstrates that in these two events a fundamental transformation takes place, the move from revolt to revolution. The thing that makes a revolution what it is, is the revolutionary plan. It is the concrete steps that need to be taken to turn the grievances of the revolt into a set of governing structures and institutions. This task, he argues, is undertaken by the bourgeois managerial class.

Technical managerialism, then, is rooted in the nature of revolutions. It is what makes them possible. The founding constitutional documents are examples of an abstract, rational plan imposed upon society.

When Ellul comes to the conclusion that the state writ large, that is, modernity itself is the enemy and must fall or be brought down, you have been prepared to receive the message. The only way out is through.